2 — My obsession

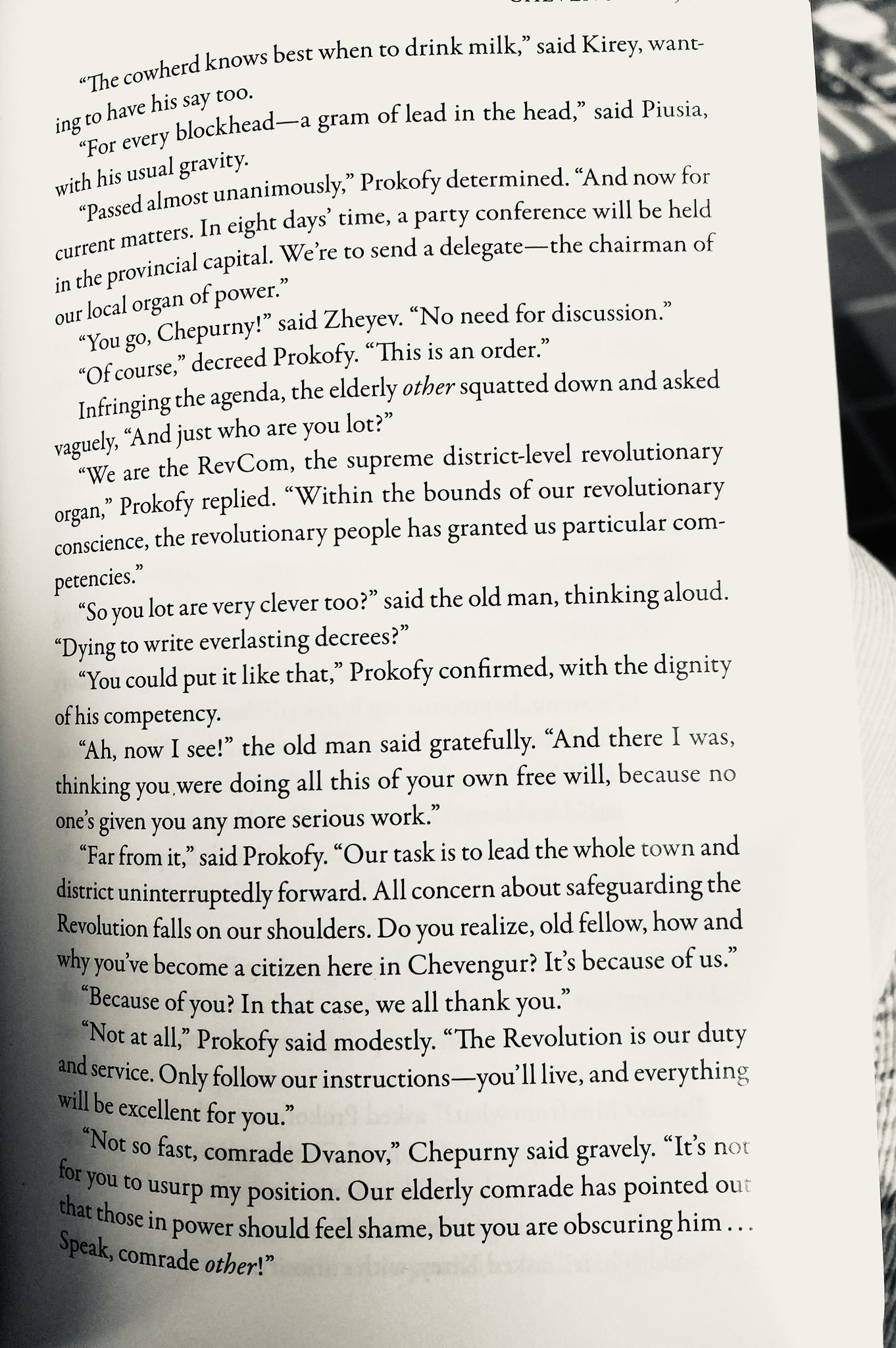

This book has obsessed me for months. It has distracted me from projects and family. It has manhandled my attention like the first reckless months of new love. My lips are raw from reading it. My notebooks and digital space are covered in Chevengur crumbs.

To get Chevengur out of my system—to “move on,” so to speak—demands a certain discipline, a reckoning with what is given as well as how the given situates itself in time, in relation to temporality. Now is not Then; Here is not There. One commences by stripping off the residual neoliberal subjectification; one tries to read in the light of the room the author presents.

Of Here, or the present US, authors often complain that biography gets over-read into their fiction. This complaint befouls itself when applied to novels written from geographic spaces where the novel plays a double-role of saying what cannot be officially “said.” I began with a biographical detail from Platonov’s life because those details perfume the book; they scent the bones and cling to his strange shifts in tense. In a sense, they also explain the decade of labor involved in the Chandlers translation. The “archive” version of Chevengur wasn’t published in Russian until 2022; the translators worked from archives rather than a published text; the presence of Platonov’s manuscript notes reveals the painstaking effort to provide readers with the definitive translation.

If definitive translations exist, then the Chandlers’ Chevengur will be listed among them. There is no way for me to link all the symbols and evocations—the accordion; the mystical moment; the spiritualism; the barracks culture, etc.—-Platonov weaves into the novel. Proceeding with for what gets left out, I self-soothe with the hope that this book inaugurates a flurry of conversations and events, a virtual cavalcade celebrating 2024 as the Year Chevengur Obsessed Us.

"The prelude to organization is always catastrophe," a younger Platonov wrote an essay titled "The New Gospel." The suffering of the "drought" and famine would be rewarded by Communism's arrival. Early Platonov analogizes communism to the Second Coming of a Messiah. Let it be noted that the formal requirement in the genre of Second Comings is how it begins in fantastic, world-destroying apocalypse.

Like all Messiahs and apocalypses, Platonov’s revolutionary scene is hounded by the challenges posed by its unrecognizability. The characters struggle with discerning the arrival of Communism from its betrayal. How does revelation differ from recognition? Who is positioned to recognize? If ‘apocalypse’ existed—-if it took place in time as an event— would there be such a thing as recognition, retrospectively? The narrative of the illuminated moment is created in the backwards glance that acknowledges it. In this sense, the moment gets lit by being written. We illuminate sacred manuscripts differently, and theory’s delight is implicated in our consciousness of doing so. Critically, the Russian Orthodox sectarians and religious schismatics who believed heaven and the kingdom of God would be established on earth were central to the 19th century zeitgeist that fueled anarchism and apocalyptic thinking. Platanov plays the zeitgeist contrapuntally in Chevengur. He links the extraordinary salvation-hunger to the abject misery produced by famine and war in Russia. Reform is no resolution.

3 — The horse the dude is riding into the sunset

"What interested me now was the transformation of thoughts into an event," Platonov wrote in an autobiographical early passage concerning the death of his mother and siblings, a passage he later removed. These deaths are not peripheral to the novel. Platonov’s mother died between 1927 and 1929, as he was writing Chevengur. We know this due to the splendid and prodigIous end-notes assembled by translators Robert and Elizabeth Chandler.

One endnote tells us that Platonov's handwritten manuscript page for chapter 25, when "Chepurny lay down in the straw," includes an unpublished note by the author: "Help me, mother, to remember and to keep living." Invocations to his dead mother's spirit ripple through Platonov's notebooks; he struggles to justify or accept the death of loved ones by imputing their value as ersatz guardian angels who offer counsel to the living. For Platonov, to know one's dead is to remain in conversation with them. "They are important," he whispers to his notebook.

Like their author, Chevengur’s characters also regularly invoke the dead as both partners and lovers. Each of the revolutionists lives alone with the ghosts in his head. The jubilant, man-hunting veteran warrior, Stepan Kopionkin, rides about on the horse named Strength of the Proletariat like a statue looking for a plinth to mount. He is the Vanguard riding the animal labor. I wept at Platonov’s genius upon realizing the symbolism of that horse named after the virtue of the exploited class’, a horse the Vanguard is riding relentlessly, riding and extolling in monologues at sunset, toasting and celebrating, theorizing ad infinitum with such profound and committed thoughtlessness that they are unable to recognize the Other they are riding when encountering it in the flesh, rather than they symbol.

Vanguard machismo aside, most of Kopionkin’s interpersonal conversations are dialogues and monologues directed to his dead love, Rosa— "He loved the dead, since Rosa Luxembourg was among them” — or his dead mother. I will be forced to return to this thread. (And I wish I had time to defend Rosa from Kopionkin’s patriarchal maw.)

4 — Aside on alter egos

According to Robert Chandler’s afterword (which deserves an its own essay), the adoptee, Sasha Dvanov, represents the idealistic Platonov of the past-revolutionary period while Scribinov represents the "somewhat disillusioned Platonov of the 1920’s.”

5 —- Digression involving another obsession whose name is Vera Figner

In 1825, the Decembrists stormed Tsar Alexander II’s winter palace, opening what some have called ‘the age of revolution’. It is indisputable that the Decembrists’ attempted insurrection altered what was considered possible. Revolutionists were born, raised, and complicated by the churn of these events. The revolutions that followed owed their gesture to the Decembrists.

In 1861, the Tsar (who had been ruling since 1818) was forced to finally liberate the serfs. This created a large class of peasantry who found themselves “property-owners” overnight. Serfs were given small plots of land that they worked for centuries. The landowning nobility and feudal class retreated to their salons and smothered themselves in luxury to quiet their alarm. Nevertheless, the salon, itself, drew reading into the spaces of power. Books containing radical ideas circulated among the children of the landowning nobility. One of these children, Vera Figner, became a revolutionist.

Figner’s Memoirs of a Revolutionist (Northwestern University Press, 1991) interposes itself against the archival imprint of revolutionary journals that foreground the labor and vision of men. Figner was 75 years old when the book was published in 1927. In the introduction, she says that one must write because "the dead do not rise but there is resurrection in books." Figner also recalls a warning from Eleanor Duse, when they met abroad: "Write: you must write; your experience must not be lost."

What Figner brings to the revolutionary memoir is intentionally gendered. She frames her intellectual journey as a series of relational epiphanies: the knowledge of self in relation to others, the ecologies of affect and signification, etc, where feelings signify. Lived experience socializes us for the roles we’re expected to play. Figner’s resistance to these roles begins early. She was fussy, hot-tempered, and spirited. She fought with her siblings until the nurse pulled her away. Then, Vera would "mop the floor," which is how the nurse described her graphic, physical, floor-writhing rage.

Her first experience of shame as a child— something revolving around a broken lock— led her to adopt her first principle. The experience of shame taught her "to take the blame on yourself." Punishment is preferable to guilt. And guilt may have nothing to do with innocence.

Class expectations loomed over her future. She loathed her time at the Smolny Institute, an exclusive boarding school for the daughters of the nobility (which would become the Bolshevik headquarters in 1917). At Smolny, she was taught to believe that she had no duty or responsibility for peasants or Russians or the masses: her sole responsibility was to those of her class.a lack of duty or sense of responsibility towards others.

Where school gave her despair, novels gave her the world. Figner insists that she learned more about life and humanity from the idealistic heroes in the literature given to her by her mother. At the same time, her early bildungsromanism included an "an abundance of joy," which Figner believed needed to be shared and rendered in common. Joy connected her to others; it created brothers, sisters, a family. And joy was not indistinct from the revolutionary character Figner acquired from literature.

N. A. Nekrasov's poem, "Saša," taught her "how to live" as a revolutionist: "To make my words coincide with my actions; to demand this consistency from myself and others. And this became the watchword of my life." (It still gives me goosebumps.) The logic of her character, in her own words: "It was incomprehensible for me not to act upon that which I had acknowledged as true.” Her soul “crystallized”, or came into itself in that Byronic key, on the day when she asked her father for advice with a difficult decision and realized he had no fucking clue. "One must make his great decisions for himself," Figner resolved. So she moved to Zurich and pursued a medical degree that would permit her to heal others. While in Zurich, she got married. But her views on healing shifted from individual cases of healthcare to the structural lack of economic conditions. For Vera, the problems of healthcare and social suffering she witnessed were inseparable. Poverty and healthcare went together. The decision to leave her medical degree behind was, to her, a choice towards life and against status. "I decided to go, in order that my deeds might not disprove my words," she wrote. And so deciding, she acted without looking back.

Around this time, Alexander Ulyanov, Vladimir Lenin's brother, was executed for being involved in a failed conspiracy to assassinate Alexander III. Theory was being negotiated in the field, on the ground, between barricades where nihilism met communism. Questions about direct action played out in prison sentences. Prison formed new solidarities between revolutionists.

Figner’s arrest introduced her to Vladimir Nabokov's father and Lev Tolstoy, both of whom occupied positions of power in the tsarist prison system. Tolstoy didn't reproach the struggle she fought for the peasants; he only asked why she had to kill the tsar, since a new one would pop up behind him. "The desire to be silent" descended upon Vera. Imprisoned for decades in a tsarist prison, Vera wore a gray prison coat with a yellow diamond patch on the back. Her co-prisoners called her "queen."

The carceral society has been called kazarmnyy kommunizm ("barracks communism") or Nechaevshchina ("Nechayevism") after Segrey Nechayaev, the Russian revolutionary whose 1869 book, The Catechism of a Revolutionary, is best known for its slogan: "the ends justify the means." Nechayev’s first article of faith is critical reading:

- The revolutionary is a doomed man. He has no personal interests, affairs, feelings, attachments, property, or even a name. Everything in him is consumed by a unique, exclusive interest, a single idea, a single passion: revolution.

- In the depths of his being, not only in his words, but also in his deeds, he has severed every link with the civil order, with the whole of the civilized world, with all the laws, propriety, conventions and morals of this world. He is its implacable enemy, and if he continues to live in it, it is only in order that he might destroy it.

[Nechayev inspired the nihilist revolutionist's character in Dostoevsky's The Possessed. Dostoevsky also based the brutal murder of Shatov, a member of the clandestine cell, on the November 1869 assassination of Ivanov, an apostate from Nechayev's revolutionary band of brothers.]

What Figner brings to history is a first-person account foregrounding women. It is indisputable that the abysmal, relentless suffering of Russian mothers created many women revolutionists, as Figner reveals. Her anarchist chafes against the imposition of teleology, a mode she associates with authoritarian Russian Orthodox leaders. No, things did not have to be this way, Figner insists. Russians did not have to suffer miserably for a god or a tsar or a notion of national greatness. Dissent didn’t have to culminate in purges and the assertion of omnipotent dictatorial power. Figner posits a sort of counterfactual hope, a relentless optimism in progress and social change. Those evil novels can be indicted for wild hopefulness as well as revolutionary character.

I mention Figner because a lot rode on the "one-spark theory" and the activist belief that Russian peasants were ready for revolution: all they needed was an intellectual spark. (Platonov circles this point in Chevyngur)…. Like American Baptist missionaries bumbling through Romania in the early 1990’s, the revolutionists brought books and lessons to their target audience. Unlike Baptist missionaries in Iron Bloc countries, Figner’s comrades actually relocated to the villages, providing medical assistance and education, and made their lives among the peasants.

Refusing the given world, building from the radical re-visioning such refusal permits, missionaries and revolutionists proselytized and sought teachable moments between the poverty, grief, flood, loss. The promised deliverance. They outlined the actions which led to salvation. They guaranteed a world greater than suffering alone, and being abandoned to reckon with it.

6 —- Foundations

While typing just now, my thoughts bumped into Zura’s, who was reading Platonov’s Foundation Pit at 12:29 am today in Turkey. (The Platonovmania is global, as it should be.) Zura’s quote it touches on the exhaustion of the mothers—-and the way Platonov dragged this obsession across various novels.