1

It always begins foolishly.

Today, it began with a poem someone posted on twitter. A title taunting me with that old gauntlet, forbidden. A prose poem by Louise Gluck. A brief narration with parabolic energy and the shadow of a riddle inside it.

I read it twice and closed my eyes. Nothing happened.

Then I googled the riddle of Gluck’s “Forbidden Music” yet failed to find any writing that deciphered the riddle. Zero. Obviously, I had imagined this riddle in order to titillate myself on a day of streptococcal-tinged parenting. I accepted my imagining as well as its failure.

2

An hour later, while cursing the rain and arguing over playlists with my daughter, the music came back to me in spheres.

“Plato,” I whispered.

“No,” the daughter added, for the satisfaction of exercising a veto.

I ceded the playlist and set off on the hunt.

“Fucking Plato,” I confirmed to my dog Radu when passing the green chair on my way to the shelf where the ancient Greeks lived. I congratulated myself on having made a bro-cave for them.

"Beware of changing to a new form of music, since it threatens the whole system," Plato wrote in that Republic of thinking men where he set out the distinction between music that produces social order (and contributes to social health) versus music that foments disorder (and must be handled cautiously, limited to a certain audience, prohibited from arousing the masses). For Plato, music shapes character and socializes citizens. Music is political—- it is “of the polis”; of the polis’ business. Being human means (among other things) that our relationship to music precedes our relationship to words, or to language as a way of knowing. The human infant deploys sound in order to intervene upon its environment; the baby develops a vast collection of evolving noises, babbles, coos, wails, and gurgles, and it does so more than other animal infants. Apart from its sound-making capacity, the human infant also recognizes its caregivers through sound. It turns its head and body towards the sound of the mother’s voice. Plato acknowledges how the lullaby, a particular form of music, can soothe an unsettled infant. Where the baby’s tumultuous wail disorders, the mother’s lullaby restores order. And order, in this definition, is the condition of social calm. Harmony reigns.

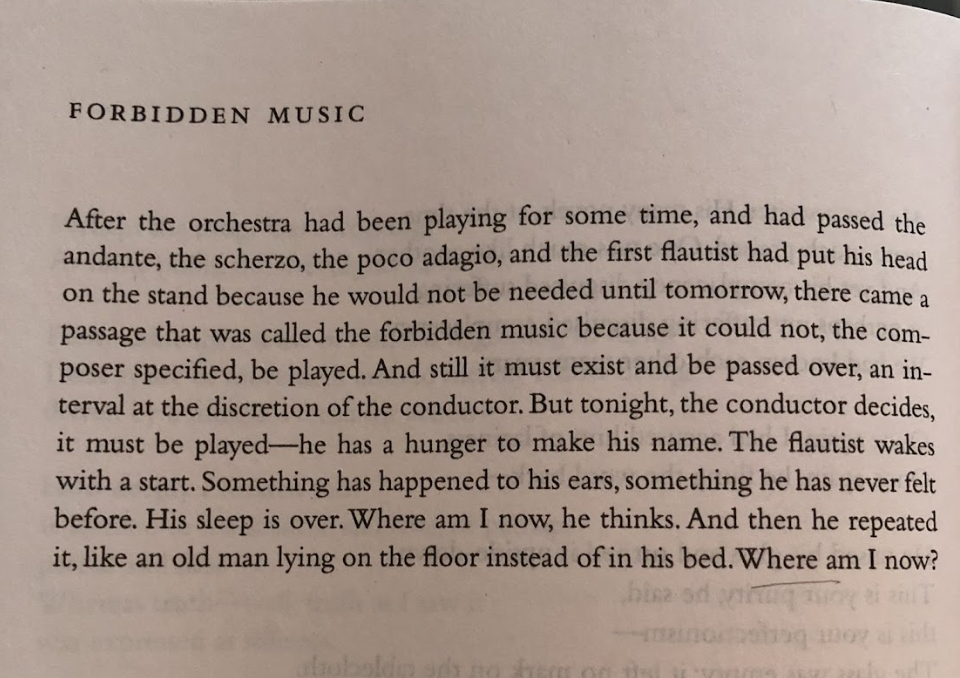

Remedios Varo, The Flautist (1948)

3

“What’s wrong with harmony?” the man asks.

A painting by Remedios Varos that calls to mind the first musician whose name history records, Enheduanna, standing near the stone disk that celebrated her importance, a disk shattered into pieces by those in power who came later. A poem that reminds me of Plato. A sense in which the forbidden must be the voice one craves most. An instant in which the andante, the scherzo, the poco adagio signify the unsayable. And the voice in my head, complicit in the imagining of this constellation.

There came a passage that was called the forbidden music because it could not, the composer specified, be played.

4

Flutes, then…for the sons of Thebes; they know not how to converse. But we Athenians, as our fathers say, have Athena for foundress and Apollo for patron, one of whom cast the flute away in disgust, and the other flayed the presumptuous flute-player.

- Plutarch, Alcibiades 2.6

In an early warning against the perils of multi-tasking, Plutarch’s Alcibiades forbids symposium participants from playing the flute. One cannot play the flute and speak at the same time because the flute “closed and barricaded the mouth, robbing its master both of voice and speech.” The flute simply wants too much—- and wanting too much, it finds itself capable of the least.

The flute’s relationship to the mouth places it in competition with language. The aulos—- a double-reed instrument usually translated as “flute” although the sound it makes is closer to an oboe-bagpipe— has the capacity to carry on a competing conversation. This language of the aulos amounts to a dialogue in musical notes that threatens to diminish the dialogue of words. This is what Plato is thinking about when he has Socrates banish the flute-girls from the symposium. It is not girls’ physical being that threatens disorder— it is their music. It is the sound that girls make with their mouths, a sound that is not ordered language.

Only when the music made by the girls is gone can the male symposiasts offer their complete attention to thought and conversation.

In Plato’s Symposium, Socrates insinuates that aulos music is only suitable for women—-it is a gendered noise.

But it is also a music for drunkards! The aulos intoxicates without alcohol. Those who listen to it become “quick-tempered, prone to anger, and filled with discontent."

5

The flute is not an instrument which is expressive of moral character. It is too exciting.

- Aristotle, Politics

Thus do the philosophers stack various arguments to evidence the anti-intellectualism of the flute. Aristotle prohibits the flute from entering classrooms. Auloi “produce a passionate rather than an ethical experience in their auditors and so should be used on those occasions that call for catharsis rather than learning.” (Politics 8.6 1341 17–24) The educated soul does not need the distraction of passion.

6

After listening to the aulos, I text my son with a question.

“You’re not even talking about music here,” my son texts back. “The Greek word for music is not the same thing as ‘music’. Or not the same thing as music as we know it.”

He is referring to the fact that mousiké designated the arts more generally— music, poetry, literature, epics, drama, dancing—-anything that fell under the domain of the Muses.

“The aulos is wild,” I text back. It reminds me of an instrument I heard played in Transylvania, although the name escapes me.

And still it must exist and be passed over, an interval at the discretion of the conductor.

7

Plato’s concerns about unmanliness led him to the law, or to the erection of legal fences that would protect the male gender from contamination. He described the sort of music most fitting for men in The Laws. The boundary between genders was theorized (and maintained) in relation to music.

8

In the cultivation of music the ancients respected its dignity, as they did in all other pursuits, while the moderns have rejected its graver parts, and instead of the music of former days, strong, inspired and dear to the gods, introduce into the theaters an effeminate twittering.

- De Musica, of uncertain authorship but often attributed to Plutarch (bolding mine)

Pseudo-Plutarch attempts to reclaim Roman masculinity from the clutches of the flute-girls. He blames them for the high-strung pitch and lament-like sound of the Lydian mode. The lament, itself, is dangerous because it attaches itself to the mouths of women and makes the mind vulnerable to intense emotions. Lamenting is for weaklings. Grief must conduct itself with poise and dignity. Speaking of poise and dignity, the Dorian mode is "proper for warlike and temperate men.” The Dorian mode doesn’t grovel; it maintains its "grandeur and dignity."

Something has happened to his ears, something he has never felt before. His sleep is over. The fall of Rome was blamed on the effeminate tastes of its leaders. Nero’s curls were too girly.

Anne Carson said it: civilization is based on the walling-out of women and their noises, their wails, their ecstasy and sirens.

Pythagoras gave us harmony, the silencing of desire, by the well-tuned soul. The unconstrained sounds of the infant, the yowling of the women— we wall ourselves against them. But this ordered world has never been enough for us. Desire, like death, eventually wins.

Walter Benjamin was the fool who chased them across borders for another glimpse and one more inch of conversation. Gershom Scholem cringed at Asja Lacis and diaried his disgust for Benjamin’s unmanly weakness. Nothing is less manly than being unable to sustain devotion to imagined community of a nation.

Where am I now, he thinks.

A nation is the only woman who loves you as you are. A nation is the only woman who can make you a hero. As every married man knows, all the manliness in the world amounts to nothing, for no man can be a hero to a woman while living inside her.

The flute player is a male Louise Gluck’s poem. But the player is also the man at the end who no longer knows where he is.

The flautist is my head is eternally femme.

The man at the end is Plato on his deathbed, asking for the forbidden music.

Recollecting his life, the dying Plato refused the well-ordered tradition of asking for time with friends and family. Instead, in these final moments, the philosopher asked for music. He did not want the well-tuned lyre of the poet. What Plato requested was Thracian girl playing the aulos. The forbidden flute called him in this moment where truth could be told: there was nothing he desired more than the allure of disorder. And then he repeated it, like an old man lying on the floor instead of in his bed.

When my daughter puts Ariana Grande on the playlist, it is as if I have imagined all of this. The distance between imagination and fabrication isn’t slight.

Where am I now?

[Postlude wherein speaker resolves to libate Xanthippe later]

I am thinking of drinking—good drinking, bad drinking, drinking music and how sonic softness distracts the mind. Woe to the enfeebled listener who “gives music an opportunity to charm his soul with the flute and pour those sweet, soft, and plaintive tunes we mentioned through his ear. … if he keeps at it unrelentingly and is beguiled by the music, after a time his spirit is melted and dissolved until it vanishes, and the very sinews of his soul are cut out,” Plato warned (Republic 411a–b).

Radu lounges and licks his wounded paw as I return to the second chapter in Plato’s Symposium.

The libation has been poured; the dead ancestors and gods got the first shot of wine; the continuance of the drinking has been blessed by the offering:

When the tables had been removed and the guests had poured a libation and sung a hymn, there entered a man from Syracuse, to give them an evening's merriment. He had with him a fine flute-girl, a dancing-girl—one of those skilled in acrobatic tricks,—and a very handsome boy, who was expert at playing the cither and at dancing; the Syracusan made money by exhibiting their performances as a spectacle. They now played for the assemblage, the flute-girl on the flute, the boy on the cither; and it was agreed that both furnished capital amusement. Thereupon Socrates remarked: “On my word, Callias, you are giving us a perfect dinner; for not only have you set before us a feast that is above criticism, but you are also offering us very delightful sights and sounds.”

“Suppose we go further,” said Callias, “and have some one bring us some perfume, so that we may dine in the midst of pleasant odours, also.”

“No, indeed!” replied Socrates. “For just as one kind of dress looks well on a woman and another kind on a man, so the odours appropriate to men and to women are diverse. No man, surely, ever uses perfume for a man's sake. And as for the women, particularly if they chance to be young brides, like the wives of Niceratus here and Critobulus, how can they want any additional perfume? For that is what they are redolent of, themselves. The odour of the olive oil, on the other hand, that is used in the gymnasium is more delightful when you have it on your flesh than perfume is to women, and when you lack it, the want of it is more keenly felt. Indeed, so far as perfume is concerned, when once a man has anointed himself with it, the scent forthwith is all one whether he be slave or free; but the odours that result from the exertions of freemen demand primarily noble pursuits engaged in for many years if they are to be sweet and suggestive of freedom.”

“That may do for young fellows,” observed Lycon; “but what of us who no longer exercise in the gymnasia? What should be our distinguishing scent?”

“Nobility of soul, surely!” replied Socrates.

“And where may a person get this ointment?”

“Certainly not from the perfumers,” said Socrates.

The men move from discussing their “distinguishing scent” to where one could find an instructor to ennoble the soul.

Socrates intervenes to quash the discussion: “Since this is a debatable matter, let us reserve it for another time; for the present let us finish what we have on hand. For I see that the dancing girl here is standing ready, and that some one is bringing her some hoops.” The dancing girl throws hoops in the air “observing the proper height to throw them so as to catch them in a regular rhythm” while the flute girl accompanies her on the aulos.

Pleased by the dancer’s well-ordered motions, Socrates addresses his friends: “This girl's feat, gentlemen, is only one of many proofs that woman's nature is really not a whit inferior to man's, except in its lack of judgment and physical strength. So if any one of you has a wife, let him confidently set about teaching her whatever he would like to have her know.”

“If that is your view, Socrates,” asked Antisthenes, “how does it come that you don't practise what you preach by yourself educating Xanthippe, but live with a wife who is the hardest to get along with of all the women there are—yes, or all that ever were, I suspect, or ever will be?”

“Because,” he replied, “I observe that men who wish to become expert horsemen do not get the most docile horses but rather those that are high-mettled, believing that if they can manage this kind, they will easily handle any other. My course is similar. Mankind at large is what I wish to deal and associate with; and so I have got her, well assured that if I can endure her, I shall have no difficulty in my relations with all the rest of human kind.”

It is too early in the day for me to take a shot of tuica for Xanthippe, but I resolve to libate her later.

The men express concern for the dancer who has now incorporated swords into her routine. She risks injury. The dancer will hurt herself!

Thus do the men worry, think, and drink.

“Witnesses of this feat, surely, will never again deny . . . that courage, like other things, admits of being taught, when this girl, in spite of her sex, leaps so boldly in among the swords!” Socrates exclaims.

Antisthenes takes this a step further, arguing that the dancer needs to be shown to the Athenians to give them an example of courage.

Philip agrees and says he would “like to see Peisander the politician5 learning to turn somersaults among the knives.”

At this point the boy performs a dance, eliciting from Socrates the remark, “Did you notice that, handsome as the boy is, he appears even handsomer in the poses of the dance than when he is at rest?”

A conversation on dancing follows.

In jest, Philip stands up and says “let me have some flute music, so that I may dance too” as he mimics the girl and boy, making “a burlesque out of the performance by rendering every part of his body that was in motion more grotesque than it naturally was.”

Naturally, after the labor of destroying a dance’s harmony by performing it mockingly, Philip is quite tired and thirsty. “Let the servant fill me up the big goblet,” he says.

Socrates intercedes:

“Well, gentlemen . . . so far as drinking is concerned, you have my hearty approval; for wine does of a truth ‘moisten the soul’ and lull our griefs to sleep just as the mandragora does with men, at the same time awakening kindly feelings as oil quickens a flame. However, I suspect that men's bodies fare the same as those of plants that grow in the ground. When God gives the plants water in floods to drink, they cannot stand up straight or let the breezes blow through them; but when they drink only as much as they enjoy, they grow up very straight and tall and come to full and abundant fruitage. So it is with us. If we pour ourselves immense draughts, it will be no long time before both our bodies and our minds reel, and we shall not be able even to draw breath, much less to speak sensibly; but if the servants frequently ‘besprinkle’ us—if I too may use a Gorgian expression—with small cups, we shall thus not be driven on by the wine to a state of intoxication, but instead shall be brought by its gentle persuasion to a more sportive mood.”

The “small cups” resolution is unanimously approved “with an amendment added by Philip to the effect that the wine-pourers should emulate skillful charioteers by driving the cups around with ever increasing speed.”

And “this the wine-pourers proceeded to do.”

Cheers indeed! In the hope that the very sinews of mens’ flute-ravished souls continue their “gentle persuasion” with small cups.