1

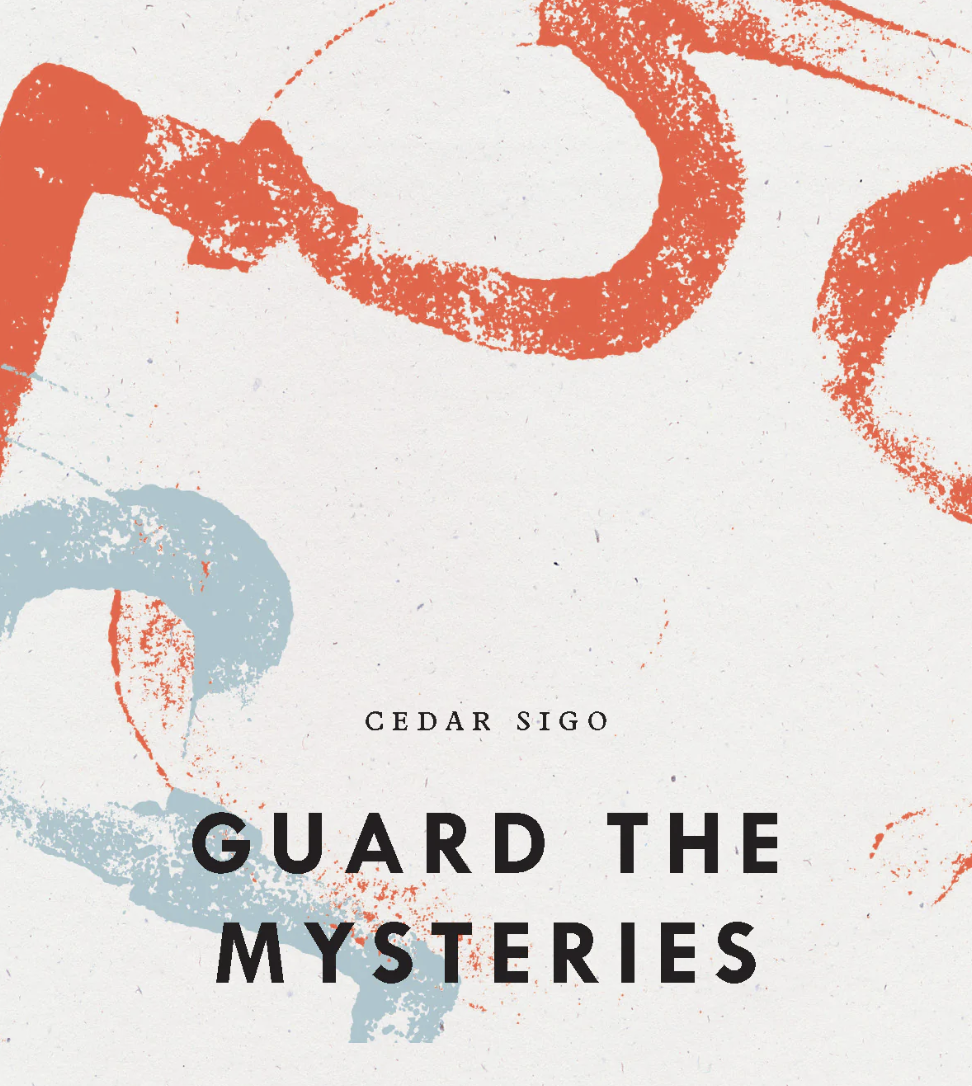

Cedar Sigo begins Guard the Mysteries, his 2021 addition to Wave Books' Bagley Wright Lecture Series, by challenging the lecture itself.

In "Reality is No Obstacle: A Poetics of Participation," he wonders if the lecture form is appropriate, or if what he aims towards is closer to the speech act. Lectures are exclusionary from the outset: the lecture form is characterized by a captive audience, the presumption of shared academic background, the positionality of the podium, the hierarchy of power which reduces the understanding of language as an event between people.

What Sigo values is a "poetics of participation" where the speech act embodies a form of cosmic intimacy which includes the living, the dead, the writers who touched us, the invisible lineages of ancestry. He makes this clear by structuring the lectures around his own literary influences, beginning with the title itself, which comes from a quote by beat poet Lew Welch: "Guard the mysteries! Constantly reveal them!" Though the second part of this quote isn't titular, revelation is central to Sigo's poetics, which probs the tension between reverence and revelation, between epiphany and exposure. The corporateality of it assumes a spirit, or haunting, a way in which ancestors (and ancestry) persists at a non-material level.

2

Against boxes and labels, Sigo maintains the poet's life as part of the poem where creation maintains a relationship between poet and cosmos, living and absent, imagined and unimaginable. "We believe in the creator," he writes, of his Suquamish family, without capitalizing the divine, without narrowing immanence into dogma or theory. Because one learns to write poetry by reading, relating, remembering, and collaborating with the words of others, relational pedagogy is a thread throughout the book, where Sigo shares resonances and biographical information about the poets in his lineage.

3

In Lorenzo Thomas' "How to See Through Poetry: Myth, Perception, and History," Sigo found an animating question: "When does the word itself become action?" Like Alice Notley, Sigo mourns the "images of dehumanization" we access through screens. The politics of heartlessness. The hunger for others’ pain. The rehashed shock-rage, a blur between shock and outrage, the sense that something should be done, grafted by an absence of vision for how to do it.

Recent political events render his former relation to language is insufficient; Sigo ponders his own efforts "to delay the meeting of edges and collage, until they fall to form the final image", or " the unlocking of collage through the inflection of voice." He quotes Amiri Baraka's assertion of freedom to do what he wants "in the poem": "There cannot be closet poetry. Unless the closet be wide as God's eye."

For Sigo, poetry is a gift that must be handed along, a source of liberation. He teaches American revolutionary poets without "stamping their work as political" anymore. To teach a poem as "political" creates a divide or what Sigo calls a "ceiling" of possibility that he wants to relinquish. He doesn't want to deconstruct but to reorient us towards one another, towards the natural world, towards music, towards the spiritual connections rather than the cadavers. For "political" may be a ceiling when the poet offers us "amulets," or things we "call upon to redefine what revolution means." These amulets, for Sigo, are words from poems, slogans, permissions, and various moments which become the touchstones in one's personal poetics. Each is liberating. Each is holier for the way it makes wholeness possible.

4

"The pleasure of the poet" is "to redefine our engagement with the way language comes to guide our lives," Sigo writes. The poem creates its own poetics, as how Diane di Prima came to write Revolutionary Letters, poems which laid aside intellectual baggage in order to be "something you could hear in one hearing, something more like gorilla theater." He queries the distance between "protest, performance, and actual battle." In di Prima's work, he finds a radical, inclusive, and deliberate cross-pollination of artistic mediums which refuses to separate the poem from the speech as action, performance, and protest. Rejecting the podium, di Prima put an amp on the truck bed and read her revolutionary letters aloud to protestors and crowds. Her audience was not academic--it was human--and this rupture created hope as an action.

The use of pronouns - the We - is part of how we relate and see each other, how we define unity. Taking a cue from her anarchist grandfather, di Prima invokes this lineage when explaining her distribution of revolutionary letters for free, or creating her own press. The poems partake of anarchist printing ethics as well as the potlatch, a revisioning of class distinctions which assumes access for all.

Amiri Baraka called it "the scalding scenario"— the "ultimate tidal wave" of humanity reclaiming each other as participants in the end of the capitalist pageant, in the leveling and self-determining. Baraka was di Prima's "early collaborator, ally, lover, the father of her second child, Dominique. She wrote letters as poem-missives to speak to him. "Revolutionary Letter #110" is an elegy for Baraka written after his 2014 death. For Sigo, the poem is a letter, a mode which inscribed the intimacy he values in the bond a poem creates with the reader.

In an essay on Audre Lorde, Sigo describes how she and Diane di Prima first met when reading poems in the home-room of Hunter High School. In 1967, Lorde who delivered di Prima's fourth child, Tara Marlowe, at the Albert Hotel. Less than a year later, as di Prima began writing the Revolutionary Letters, she also published Lorde's first poetry book in 1968, the seeds of life shaped like a poem between them.

When demonstrating how a poem gives rise to its own poetics, Sigo points to Diane di Prima's Revolutionary Letters, which laid intellectual baggage aside so that the poems became "something you could hear on one hearing, something more like gorilla theater." Sigo queries the distance between "protest, performance, and actual battle,” turning towards silences, quoting Audre Lorde's reasons for writing The Cancer Journals: "to break one silence, one aspect of the kind of silences we partake in as women." For Lorde, the "responsibility" was inseparable from the calling, and the defiance of labels. "I am a poet," Lorde insisted, when her editor attempted to describe her words as "theory." To be a poet included all the ways poetry laid claim to language, or narrowed it by labeling.

The inventory—this listing of all the things one—is may be a revolution in poetics, as well as a widening form for Sigo, who values the lens which stays open, blurry, unsettled. In his attention to particular forms, Sigo seems to value the luminous vessels, those which also serve religious or spiritual purpose. The litany is a list of praise. The psalms are anchored in repetition and invocation of proximity to god. There is an undercurrent of reverence that insists on vision rather than nihilism.

Lorde's poem, "A Litany for Survival", is a sort of list which relies on shifts, motion, and refrain - "We were never meant to survive." The pronoun, this We, is a site of poetics for Sigo, a permission to open the personal and historical silences of his Suquamish ancestry. He notes that Lorde did not give herself this permission at first. Instead, she spent a year writing rage, fury, fear into her notebooks only to return, later, and discover many of the poems which would become The Black Unicorn in her notes. Only when she was able to assimilate the journal entries into her lived experience could the poet begin to inhabit the poems – "only then can I deal with what I have written down," Lorde said.

Both the list and the chant are poetic modes that rely on repetition. "Incantation and chant call something into being," Joy Harjo wrote, "they make a ceremonial field of meaning." Harjo locates much of global poetry in the incantations and chants, the song forms, the local dirges, and Sigo believes the poet "becomes what they are singing," being filled with recurrent rhythms and breaths. Repetition refines and sharpens and renders more luminous.

5

Arguing for a poetics of participation, Sigo takes Diane di Prima's "Revolutionary Letter Number 62" as a model for how poetry is closer to a speech act than a lecture. The word, itself, becomes action when it insists on intimate address and vision. Sigo pries apart di Prima's use of pronouns to implicate herself, or to reconsider complicity, to note how the interstices of we and they are spoked.

But the poem’s speech also elects its interlocutor. For example, Amiri Baraka was Diane di Prima's early collaborator, ally, lover, the father of her second child, Dominique. di Prima communicated with Baraka through poems, including the elegy "Revolutionary Letter #110," written after his 2014 death.

6

In "Becoming Visible," Sigo describes intimacy as "scaling the gaps aloud." The spoken word is part of the poem's form, and every lecture he's ever given returns to form, defined as "how to convey the passage of the language through and body and down onto paper, and then to attempt to replicate that in the reading of the poems aloud."

Both of Sigo's parents are artists whose practice focuses more on process and daily commitment than "mastery." Sigo's father, a photographer, served as curator and archivist for the Suquamish Museum. His mother is a singer. Although his parents honored their Suquamish roots (his father kept his hair waist-length), neither aspired to a purist affiliation. Neither valued tradition as a form of static orthodoxy, and Sigo expresses this by saying his father preferred to "leave it open-ended." But Sigo was imprinted by the connection between native prayers and poetry early on. He felt "haunted by the responsibility of making poems and drawings as a child", and the belief that art is a form of medicine.

In 8th grade, Sigo told his parents school was "too slow," one way of saying queerness didn't thrive in the box. Homeschooled since then, Sigo's poetics isn't unschooled so much as deschooled--which is interesting given his educational background. In this, his allegiance to the New York School of poets and the Naropa Institute occupies a foreground, and his words continue a dialogue with this lineage, influence, and approach to authority. "The pleasure of the poet is to redefine our engagement with the way language comes to guide our lives," and this, for Sigo, is a luminous task— "taking on reality in luminous particulars."

Sigo's sense of time is not linear or fixed. He credits Joanne Kryger with inspiring a loose temporality in the poem, a time where "the body itself threatens to become an afterthought," and the poem travels along "anointed pathways," growing in spaces which reconfigure time and recreate it. In opening time, in reaching through the material shapes we worship, across the particular embodiments and labels, Sigo imagines poetry as a site of communion, as a restorative place which uses traditions not to displace or replace but to reimagine entirely. To create a Suquamish poem located in Suquamish time, one which includes the invisible. Perhaps this is a form of queering for consumerist cultures like ours.

He mentions his father's waist-length hair which was not including a claim to be the "most traditional", and struggle was not something which belongs completely to the Past. "Misfortune often arises whenever we stop struggling," Sigo writes - and so the struggle is part of time, part of presence.

"Things to do" poems, a form popularized by Gary Snyder and quickly expanded by Ted Berrigan, offer insights into how he frames a poem. Sigo mentions "Things to Do in Providence" by Berrigan as one of favorites: the poem becomes a list as it goes on, and the asides become more necessary, illuminating. By allowing time and candor to slip into the asides, Sigo says the distinction between form and formula disappears. The formulaic is integral to this form, and so the fun comes with ruining the vehicle.

7

"There is no death, only a change of worlds," Chief Seattle said in 1854, closing a speech to his people, as quoted by Sigo..

Im a culture built on planned obsolence and perpetual novelty, it is revolutionary to say "the dead are not powerless" — and, comforting…to me, this invocation of ancestors in contemporary American poetics is comforting. Ancestors unsettle the living with eternity. In our attention to them, we are forced to listen, to be supplicant, to imagine alternative modalities of respect. This looking-beyond is dangerous to worldviews based on immediate gratification. The dead are not here for the commercial culture, and respect for elders and ancestors may be one of the most radical challenges to consumerism.

Charles Olson helped Sigo expand his field of vision to include the available energies in a place. The energy of academic poetry is vaguely mentioned as a relief that Sigo was lucky to have avoided, "the construct of Academia hanging over my syntax in anyway." This, I think, is part of the commitment to sitting, to being in the body, to taking that relationship as authoritative.

Sigo learned by exploring his fascinations—The Black Panthers, political slogans,The Fugs, Allen Ginsberg's Snapshot Poetics with photos. He still keeps Ginsberg's proclamation close: "Candor disarms paranoia!" Proclamations, speeches, slogans and posters are formative to Sigo's poetics. Eventually he wound up at Naropa, which Ginsberg co-founded with Anne Waldman.

Writing autobiography as poetry allows us to leave the gaps intact, which offers a more "complete" portrait. He is dissatisfied and restless with his books by the time they get published - he has already moved on to the "untyped poetry" in his notebooks, and the intensity of the time they occupy. Ending this lecture with a poem, "Smoke Flowers," enables Sigo to show us the poem as autobiography in practice.

I soon left school for dreams of the lyric (of building)

I lied and said the lessons moved too slowly

.....

I became a warrior surprised at what I still didn't know, how to get started,

Move along, stay moving, how to fill the page all over.

8

Barbara Guest taught him that collage doesn't have to be constructed from or after, but can be created during the poem, as part of its existence, time signature, and scoring.

Joanne Kryger inspired Sigo's interest in a temporality where "the body itself threatens to become an afterthought," and the poem travels along "anointed pathways," growing in spaces which reconfigure time and recreate it.

"Sometimes the life of a poet is itself a kind of poem that must be orchestrated and arranged for impact (preferably by someone else)," Sigo explains. It is immersive, demanding, a sort of absolute imaginative commitment, this writing of biography, especially when dealing with mythology, or with Joanne Kryger's complicated place in the Beat tradition. He dedicates an essay to her memory, tracing the relationship which leads to the collaborative 2015 project of collaging old interviews and "illustrating this chronology with ephemera from her personal archive." Ephemera offers new trajectories into personal history – and we see this in the selection of images, photos, posters, portraits—a practice Sigo repeats in this lecture text.

As the poet's pleasure is "to redefine our engagement with the way language comes to guide our lives," Sigo credits Kryger with inspiring a loose, nonlinear temporality in the poem, a time where "the body itself threatens to become an afterthought," and the poem travels along "anointed pathways," growing in spaces which reconfigure time and recreate it.

9

As poetry expands time across particular embodiments, Sigo describes it as a site of communion, a restorative place which uses traditions not to displace or replace, but to reimagine entirely. To create a Suquamish poem located in Suquamish time, one which includes the invisible, to queer our appetite for terminal consumption.

For Sigo, each poem we read and remember, each "resonance," becomes part of our inherited lineage. Unforgettable lines are "drifting medallions" which enable the poet to survive when he least expects it. US Poet Laureate Joy Harjo invited him into Native poetry by asking him to co-edit When the Light of the World Was Subdued, Our Songs Came Through: A Norton Anthology of Native Nations Poetry. In his introduction to the anthology, Sigo speaks of reconnecting with memory through stories: "I remember stories of Suquamish women leaving for several days on summer journeys over the Cascade Mountains into Eastern Washington to gather luminous bear grass, those pieces that would sometimes tell stories along the outer surface of our baskets." This image and action -- to gather the luminous bear grass -- combines Sigo's spiritual commitments with his understanding of poetry as a space of communion, a gathering of spirits and stories, a home for all ephemera and impossible visionary forms.

10

"There is no death, only a change of worlds," Chief Seattle said in 1854, closing a speech to his people, which Sigo quotes. To create a Suquamish poem located in Suquamish time, one which includes the invisible, queers the present focus on materialist consumerism. In a culture built on forgetting and erasing, it is revolutionary to say "the dead are not powerless." Invoking the absent into contemporaneity allows ancestors to unsettle the living with eternity. In our attention to them, we are forced to listen, to be supplicant, to imagine alternative modalities of time and respect. This looking-beyond is dangerous to worldviews based on immediate gratification. The dead are not here for a commercial instant's hot-take or hashtag effluvium.

11

Form is how we "convey the passage of language through the body" and onto the page. Sigo isn't a poet of the finished product (acknowledging that, by the time a book gets published, he is no longer fascinated by it), nor is he a poet of the production (which is related to branding). He has little to say about how to write a poem correctly, and much to celebrate in the forms and modes which inspired him, paying particular attention to the list form, the chant mode, "things to do" poems (as popularized by Gary Snyder and Ted Berrigan), political slogans and posters (The Black Panthers, The Fugs), Allen Ginsberg's Snapshot Poetics with photos, proclamations, journal forms, notebooks, Billie Holiday, improvisational jazz techniques, the "devotional quality" of writing by visual artists (including Agnes Martin, Philip Guston, and Joe Brainard).

Although Sigo doesn't name Rainer Maria Rilke, there's a sympathetic resonance in Rilke's description of music as "a breath of statues" that draws us into intimacy with the beyond. And in Rilke's embodiment of Rimbaud's poet-as-Seer, allowing the outside to accumulate within the flesh until it emerges in a poem, which is to say, revolution.

12

Sigo's poetics returned again this week when reading Jason Allen-Paisant's "Silence, Sound, Ceremony: The Poetry of m nourbeSe philip," noting how philip's multi-medium, polyvocal ceremonial poetics shares a visionary stream. In Allen-Paisant's words:

"Language is always an insecure place. The language of the poet performs this insecurity, the recursion of past and present, of the past in the present. To be displaced from language is to be physically displaced. Yet the answer to this alienation must be poetry itself. So the poem is reconceived as corporeal habitation. Corporeal because it embodies its subject matter; Corporeal also in that it places the body in action. The poem is no longer an object; it is a space of gathering (s)."

The space of gathering is one where the dead are permitted to speak by the poet who lets language lead, who opens to body to mystery and enchantment, who engages the ceremonial to invoke silences, breath, and ritual in which gathering is both created and embodied. "The pleasure of the poet is to redefine our engagement with the way language comes to guide our lives," and this, for Sigo, involves"taking on reality in luminous particulars." There is a physical and spiritual wholeness to this living poetics which relies on an ontology conceived from time and community, an invocation that is also a libation, a sharing of gifts with the dead, a listing of names, evoking the missing—not just as elegy but as epistolary, as dialogue, as evolving incarnation.