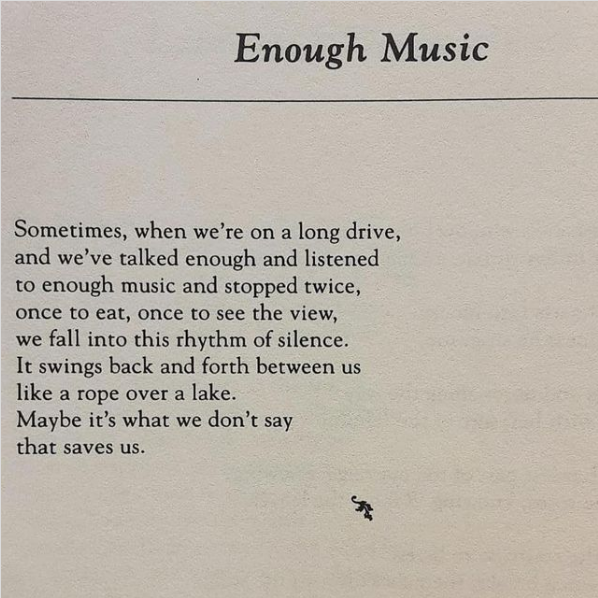

Reading Dorianne Laux’s short, one-stanza poem “Enough Music” this morning, and thinking about the swinging of “this rhythm of silence” between the speaker and the subject—-and how Laux refuses the easy image of the pendulum, choosing instead the playful possibility of the rope over a lake.

This poem is made, somehow, from its refusing the pendulum—-and the notion of time that it invokes.

Because I am thinking about music, time, motion, and memory—-again—-the rope swaying over the surface of the lake gathers itself in reflections and intonations of light.

The mystery of music— how vibrations in the spectrum of sound lead to complex reactions in humans. No theorist has yet resolved it. No neuroscientist has found a singular, cohesive explanation.

One of my favorite performances of Mahler’s Ninth was conducted by Michael Tilson Thomas—-who is also a notable composer.

At at one point in this brief video, Tilson Thomas traces the music in the sounds of kids on the street:

One day in New York, I was on the street and I saw some kids playing baseball between stoops and cars and fire hydrants. And a tough, slouchy kid got up to bat, and he took a swing and really connected. And he watched the ball fly for a second, and then he went, "Dah dadaratatatah. Brah dada dadadadah." And he ran around the bases. And I thought, go figure. How did this piece of 18th century Austrian aristocratic entertainment turn into the victory crow of this New York kid? How was that passed on? How did he get to hear Mozart?

Well when it comes to classical music, there's an awful lot to pass on, much more than Mozart, Beethoven or Tchiakovsky. Because classical music is an unbroken living tradition that goes back over 1,000 years. And every one of those years has had something unique and powerful to say to us about what it's like to be alive.

As a conductor, Tilson Thomas’ interpretations have changed the way pieces are experienced. I’m thinking of Mahler’s Ninth, and TT’s statement “the main melody of the piece that is only heard in at the climax of the first movement” becomes “klezmer-like in the second and third movements.” And how Mark Swed interprets TT’s Mahler’s as using the kletzmer to tell us “what people thought of him,” before moving in the extraordinary cavalcades of the final movement.