In a silence-laden space, it can be difficult to distinguish the silences from what they carry--and that, of course, is why a writer creates a silence-laden scene which disorients the reader and adds tension.

Read MoreTime-signatures in prose.

Their faces are bright patches with hairdos.

I started thinking about time-signatures in prose after reading this descriptive line by Judith Schalansky, narrating from the child POV (in an essay), and how quickly the image lends itself to a child narrator, or to the way a child might describe something. It is literal, bold, unselfconscious—the faces are what they are, the child passes this information along casually—and the reader is given a time that reflects the narrative perception.

When I say time-signatures, it is to bracket the way different writers describe time in their prose, and how images, metaphors, and figurative language intersect with voice to reveal intent. A time-signature is part of narrative craft, a way in which time is both created and evoked.

.. my family lived less than a mile away from one site where the world would begin to end.

Gary Fincke’s “Faith”, published in a recent issue of Pleiades, also offers a distinct time-signature: a Before which wanders between the retrospective adult and the child. Fincke grows up near missile silos during the Cold War, where he and his friends practice drills in preparation for nuclear disaster. The time-signature here is apocalyptic but also childlike, innocent of investment or complicity. (I wish I could link to the actual text, but I can’t, so I’m leave this interview with Fincke instead, as a consolatio.)

Time belongs to adult men, Fincke suggests: "The rest of the day waits like a woman he's paid for." But time also empties itself of meaning and resonance when those men disappear, as when: "My father's garage is hollow where his car has been gone three years, sold and replaced with the emptiness of nostalgia."

Watching a real estate seller at work, his mind mapping property values, Fincke’s narrator adds: "Soon there will be nothing but borders." Here, the prophetic reaches towards the apocalyptic through the speculative—which brings me to Choi Jin-Young.

“A group of Koreans are making their way across a disease-ravaged landscape—but to what end? To the Warm Horizon shows how in a post-apocalyptic world, humans will still seek purpose, kinship, and even intimacy. Focusing on two young women, Jina and Dori, who find love against all odds, Choi Jin-young creates a dystopia where people are trying to find direction after having their worlds turned upside down.” (Source: Honford Star website)

Choi Jin-young's novel, To the Warm Horizon, was first published in Korea in 2017, prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. (I am still in love with Honford Star’s cover design!) Translated from the Korean by Soje, To the Warm Horizon creates a post-apocalyptic world changed by an unnamed virus. Although this virus wrecks the world as it has been known, it isn’t the greatest threat to life; that role is reserved for humankind, who finds ways to mobilize violence and war rather than care. How people respond to disaster creates the hinge for suspense.

Jin-young’s time-signature is part of how verisimilitude is established—and its effectiveness is critical to our relationship with the characters. It is post-apocalyptic in the most realest way – at the intersection of government’s failing, leaders fall, citizens looting, private militias terrorizing others, visa crises, and continuous refugees running, running towards something. There is an element of hindsight that touches the reader, a thick taste of rue in feeling one has averted a crisis.

The story takes us through the ravaged world as people from Korea flee across the continent towards Russia, seeking safe, virus-free (i.e. human-free) places to settle. The chapters alternate between first-person narrators who stories are tangled, each of these characters becomes precious the reader.

Ryu, a character, begins the book with two questions:

Have you ever heard of Korea? Is Korea still where it used to be?

Immediately, we understand that the address is intimate; the interrogative references something which may no longer exist. We are in the future. She is the wife of Dan, the mother of Haemin, a son who lives in Warsaw, and the mother of Haerim, a daughter who died at 11, whose death is the reason they fled Korea.

The world changed suddenly, Ryu explains, and yet they found ways to believe the virus with vanish— that government policies and modern medicine would protect them. They persisted in these beliefs until Haerim died suddenly at school. After arriving in Russia, Ryu describes finding a god whom people believe will protect them, but Ryu has "survived this long" not due to god's power, might, or care. Ryu has survived due to god's "indifference."

I am now over seventy years old—no, eighty? I’m not sure. I have lived for too long. Relative to my years, the two months or so I spent in Russia would at most amount to a single sheep in a herd of a hundred. And yet that one sheep remains so vivid in my memory. Not at day goes by that I don’t remember you all.

Survived this long. What a way to open a speculative novel—to create tension while also placing the idea of survival, itself, into question. And: you all, that strange invocation. What does it mean to survive cut off from one’s family and children? How does surviving require one to address a letter to the world, asking about one’s homeland? Set before the rest of the book, and separated from it, Ryu's story serves as a prologue which establishes context.

The first chapter is narrated by Dori, whose parents are dead, and whose sister, Joy, is now in her care. Their parents died believing humans were intelligent and persistent - humans would find a solution if one waited and listened. But Dori believes humans will create a bigger disaster, and life will be determined by those who find opportunity in it.

Disaster, itself, creates new hierarchies of power based on access to basic goods. Part of the conflict in Dori’s story is avoiding the opportunists who are harvesting children's livers for folk cures. Here is how Dori describes the way time has changed:

If nothing had happened, nothing would’ve happened.

We would’ve continued to not own the house we lived in. We would’ve started paying off another loan as soon as we were done with the first. We would’ve occasionally pushed death aside with the words, I'm so exhausted I could die. We would’ve whittled each of our own lives away, silently and ever so calmly.

The subtle contraction of would and have suggest that Dori is younger than Ryu—and not of the same middle-class, a fact the author gives us in describing the life between loans. For Dori, the disaster is not metaphysical, not inflected by Blanchot—it is simply a continuance of the struggle to survive, to devise a plan by discovering the opportunity.

Much of Dori’s character is revealed when she meets Jina, a fellow refugee with "blood-red hair,” a daughter of men with guns (one of whom will eventually rape Dori). When Jina savors a potato, Dori wonders how she can make such a fuss about a single, tasteless, root vegetable:

That might have been Jina's hope. Hope beyond that of crossing the border or finding a bunker. To live well in the now instead of recalling the past and being miserable or anticipating things getting better and forcing her upon herself.

And Dori compares herself to Jina, compares their positions in the apocalypse:

What misfortune wants is for me to mistreat myself. To look down on myself and destroy myself. I'll never come to resemble this disaster. I won't live as the disaster wants me to live.

This comparison—and this friendship—enables Dori to refuse to be swallowed by the disaster, and to assert ethical boundaries on the actions of surviving. The way that Choi Jin-young moves between tenses and times is fascinating—it is the pulse of the book.

One more quick example. In the middle of the book, Ryu narrates from the period prior to the onset of the pandemic. She describes her marriage, her husband’s infidelities, the struggles of childcare alongside maintaining her own career. The logistics, time, and emotional labor of divorce strike her as “a hassle,” though she does consider it. Ultimately, Ryu survives her pre-pandemic life in Korea by “purging memories”, pretending things never happened.

That also occurred to me daily. The feeling of sitting in an empty playground, swinging back and forth between this is fine and is this fine.

This is fine vs. is this fine. Jin-Young repeatedly lays the ethical questions of the disaster over small, personal choices in the characters’ lives. The time-signature is unforgettable. As is the book.

My mom embroidered this shirt on a vacation when I was young, and I still have it. When I found it yesterday in a drawer, I thought about vows, promises, commitments—the things we use to define ourselves—and how I have broken almost all of them. How a relationship to a vow is its own temporality….. and how I wish I could laugh with Mom about all of this.

10 vows, mostly broken.

Our neighborhood has magnolias trees that turn into babas at night. The retired probate judge to our left owns a dog that roams free. At night, the dog comes to the hill near our house and lets me pet him. He has fleas. I want to grow up so I can save money and drive the dog to a place that will help him stop itching. It hurts to watch him quiver and scratch, to watch the tiny dark dots leap from patch to patch over the abyss of white fur. I am already sorry for what we do to animals we can't claim to love. I vow never to have a dog or children.

I am 8 when the first list begins. A list of men. This one is populated with the names of my parents male friends who berate or insult their wives in public. At first there are only seven but one day, on the back porch, I listen to the dads talk about wine and two of them say they are chained, while another calls his wife a prison. They laughed as they speak but I add their names to the list. Soon I have ten such men. I vow never to marry a man and let him turn me into a prison when I am sleeping or feeding his children.

It is American Easter. My friends carry their baskets like bouquets - some have their first and middle names embroidered along the edge of pink-and-white checkered fabric. Since my mom did not send a basket to school, the teacher lends me a plastic bag. My name is Dollar General. The girls with the cheaper baskets laugh loudest when a girl with a fancy basket jokes about Dollar General. They laugh to win the favor of the powerful girl, which is always the one that has the fanciest basket. I don't want to celebrate American Easter or compete with others for plastic eggs. The teacher asks why I'm not participating. I say it is nice to watch others get what they want, and watching is my way of being present. But I am afraid of the girls, their laughter, the word friends.

This is the year of the dogwood, the age when names left stones begin to haunt me. Emily Dickinson understands. There is a boy I want to kiss on a swing set. There is a novel by Nikolai Gogol on my nightstand, a land where a character purchases the dead souls of serfs to turn absence into money. I vow to remember love without worshipping the color of absence, the echo of parents' arguments wreathing the porch.

Between train stations and Greyhounds, the world grows eyes, ears, wings. I spend hours speaking to strangers about things they have seen, desired, or imagined. Did you know Anton Bruckner barged into the chapel where Ludwig van Beethoven's excavated corpse was being studied by scientists? Bruckner was 64 when he stole Beethoven's pince-nez before being forcibly removed from the chapel. Beethoven was dead but Bruckner was elated to share a pince-nez with Beethoven's bones while finishing the drafts of his 8th Symphony. I vow to keep moving, touching, tasting, learning.

I am 16, 17, 20, 22, 23, 25, 27, and then quiet each time a friend or a friend's family member dies in a drunk driving accident. I vow never to drive late at night or during fireflies.

I am older, wiser, unbelievably married, the mother of articulate mammals. My husband hugs me when I cry on anniversaries and pick a bouquet of weeds for the girl I left behind to become a wife. We go for long, restless hikes along rivers. I want to tell time differently. When the breeding naked mole rat – the den's single, gestating mammal – gets pregnant, all the colony members, male or female, experience swollen, growing teats which reach their peak size at the birth only to begin shrinking immediately after. Just prior to birthing a litter of pups, the pregnant naked mole rat runs wildly through the underground tunnels, crashing, screaming, thrilling, and tapping her tongue. Most pups don't survive. All the naked mole rats are blind. A non-blind naked mole rat would be tortured by sight. My son says naked mole rats have magnets inside their membranes. I vow to write a book narrated by a naked mole rat who creates a nation-state.

I celebrate Ovid's nickname, Big Nose, as evidence that my own sizable infrastructure is lovely. The world is too large for our narrow, button-nose aesthetic. People have noses bigger than hats, wider than luna moth wingspans. I vow to try and love the unusual part of me.

In this land, I drink fancy cocktails near tea lights, and there are no crickets to make the night feel real. One friend rages against dying her freshly-grayed hair. She says, I am going to grow old naturally, fuck the patriarchy, pass the pink zinfandel. This space is familiar, and I note how its boundaries change every year to include new aspects of female hygiene and grooming. The problem of women dying their hair pink or brown or getting a nose job or breast reduction assumes that these things have moral value, which is to circumnavigate the argument for personal autonomy, which is to replace one body policing regime for another, which is to say women have made an industry of doing this to each other for centuries. I want to sit at a table of complicated beauty: scars, imperfect teeth, body variance, human beings who regard one another with the fascination given to works of art rather than magazine glossies. I vow to bleach my hair ad infinitum and never trend.

Another friend says she feels fake because she got her nose done, and she wishes she could reverse it, or be the self that existed before the revision. The grass was greener with a small nose, and now the grass is greenest with the original nose. It's a bad example of self-love for my kids, the friend says. I put my shoe over her shoe and tell her to stop it. A so-called "natural nose" is not more moral than a "fixed nose" - the problem isn't our noses at all. The problem is our obsession with valorizing some aesthetic ideals over others, whether thinness, curviness, white teeth, "natural skin", etc. Life gives us so few choices about how our bodies will be used or injured. The choice to explore and imagine, to inhabit these sacks of strange flesh, shouldn't be punished by puritanism, no matter how healthy Puritanism claims to be. And besides, how does natural include a Peloton and a weekly massage? Surely nature is a mess and less expensive. I vow to leave wildflowers on this friend's windshield with a love letter and a limerick.

Outside the art museum, my children hunt pigeons, the plaza-adjacent fauna. I take stock of my urges and moral failings, including the impulse to flabbergast the wealthy lady whose servant or nanny carries two dogs like a train, a system of tired choo-choos. There are no pigeons present at all. The son samples a bread crumb. The youngest daughter removes a green gumdrop from her mouth and sets it in the monument's southern-most orifice. There, she points. It looks vivid. Our attention swerves towards a child with a leather umbrella the color of church shoes, the glamour of first communion spectated from a pew, the memory of my friends promising miraculous things for the favor of broken bread laid on their tongues by a man who often wore a brass tiara. The line outside the museum does not move, but a fellow carrying a poster and a banjo offers free infotainment for cash prizes; he accepts Venmo, Bitcoin, credit cards. The sun torches all shoulders equally. It is summer. It is endless. And I remember the elderly librarian who told me I smelled of molding books and wet cinnamon when I asked if he was an archive on the day twelve televangelists swore the world had ended, and what we were experiencing was an illusion or an afterlife. In the early stages of something unpredictable, I vowed to read more translations.

52 poetry prompts (& a list of angels).

Free-write whatever comes to mind after reading the above excerpt from Helene Cixous’s Stigmata: Escaping Texts.

“Any soul may distribute itself into a human, a toy poodle, bacteria, an etheric, or quartz crystal,” Mei-Mei Berssenbrugge writes in A Treatise on Stars. Write a 7-line poem that distributes a soul into an unusual object that needs it.

Write a poem that touches a corpse without flinching.

Use Robert Pinckney’s “Lifeboat” for an ekphrastic elegy or ode.

Charles Wright once said that "all landscape is autobiographical", and psychogeography inflects poetry, whether erotic (per Richard Siken) or identity-shaping (per regional poets). Forrest Gander's Lynchburg writes from landscape, which is to say, Gander creates a landscape of certain words, a wordscape of living textures. Write a poem centering landscape as biographical subject.

Write a poem from the perspective of the tea-cup in the hands of stranger who speaks a language you can’t understand.

“The sun, in winter, is an estranged event, almost strident, as it comes in slanting...” Ann Lauterbach gives this to us in "The Night Sky VI". I love her comparison of season's sums, what they give, what they take, what they deploy leaving a context--an existing heat, or light, or whatever else we use to describe what amounts to the thing that sustains us. Lauterbach prefers winter for its "episode, the event, the quick kiss in frosty air." Write a poem about what seasons give and take. Address it to a parent or a caregiver.

Catasterism, the practice of comparing individuals to stars in poetry or narrative, originated in ancient Alexandria, with the Catasterismi (Greek: Καταστερισμοί Katasterismoi, "placings among the stars"). It’s all very exciting and it led to a habit of addressing individuals as those particular stars in poems. Use catasterism in a poem about a person. Pick a constellation. Or pick several. Or invent a new one from existing constellations.

Pick a favorite poetry book. Now write an index poem that lists fascinating phrases or ideas or objects or places or people in this book. Structure the poem as an index which includes page numbers. No integument or explanation: just a list.

Pick up a literary magazine and sit with it for a few hours. Go through the poems (or prose) and make an inventory of lines that you love. Then go back and create a list mag cento from them. Of course you can craft a cento from lines in a review or an essay as well. You can do anything that presents itself to your mind with enthusiasm.

Pick a word. Broach. Gas lantern. Free associate around that word. Or choose a letter and make a list of associations--emotional, fictional, scientific, clinical, commercial, religious, social, prescriptive, etc. Use it as a starting point.

Write a poem for which an insect you have never seen is the interlocutor.

Alice Oswald said she came to poetry from childhood terror and being alone in a room at night. She was eight years old and had found herself alone and terrified through the night in “this scary room”. “I saw the dawn coming up and I realised I couldn’t describe it other than in a different language,” she recalls. “I still remember the white clouds in the blue sky and the fact that they weren’t saying anything about what I’d been through, though their actuality was very communicative.” Write your own poem of origin. Or write a poem about the memory of being a child in a room at night, knowing that something existed which you couldn’t explain to adults.

Write a poem about a playground. Invite an exterminator into it.

In Ancient Greece, worshippers left offerings to the gods on the temple floors in mangled heaps. Describe one of these mangled heaps, detailing the offerings, the person who left it, why they left it, what they want from the god.

Now write a poem about a single object in temple offering heap. This offering attempts to trick the gods by asking for something that seems appropriate in order to get something that seems inappropriate. Give us details.

Write a list poem or instructional map guiding us back to your childhood, through its secret routes and landmarks, to its hideout, the magnolia where you practiced your first kiss on the back of your hand.

Reflection, interruption, and expansion are techniques that help thicken the resonance. Aim for a bisque. You are writing a poem about visiting a graveyard, the endless parade of flowers, the rotting red carnation who reminds you of prom, of not having sex for the first time when you planned, of failing in a interior sense, of finding yourself alone near a trash dump leaving the fake satin wristband flower as a memento. His name was Jerry. Like the one that died in 1917 from the influenza pandemic.

Write a poem addressed to Kay Ryan, in response to her statement: “I think poets should take the lesson of the great aromatic eucalyptus tree and poison the soil beneath us.”

Write a poem from analogy. Read Samatar Elmi’s “The Snails” for an example or model.

Babies who die before they can speak will rule the world after it ends. Introduce us to one of these babies.

Write a self-elegy.

In “Of Things Gone Astray”, Janina Matthewson writes: If left unused, conversations can grow rusty over time. The opinions and feelings we’ve expressed before, when left to their own devices, can grow sluggish and curmudgeonly. They become too used to sitting alone and unconsidered, and if you ask them to move, their joints can ache, or parts of them can crumble away. Sometimes you can return to an opinion you’ve not visited in years and find it’s died and rotted away without you even noticing. Sometimes a feeling we assume we’ll have forever can abandon us and leave a gap we don’t notice until we suddenly feel the need to call upon that feeling. Write an elegy to an opinion you once held that has died. If the opinion is shameful or embarrassing, even better—subvert that shame by narrowing it into sonnet form.

Captive magpies are the only birds who remove a sticker placed on their feathers after seeing themselves in a mirror. Write a poem that grows from or includes this strange fact.

"Wrongness has its own color and it is not like anything else,” Anne Carson wrote in her essay, "Totality: The Color of Eclipse." Write a poem with fourteen lines, a vestigial sonnet, that describes the color of wrongness. Include an insect and turn at least one verb into a noun.

Mary Cappello calls the lecture "nonfiction's lost performative"; the lecture’s origin lies in "the note," that morsel allotted to space in a notebook. The good lecture "errs on the side of rapture rather than vehemence." And the notebook is "the lecture's tipping point;" it "combines the energy of containment with the velocity of scatter." Of course you should write a lecture poem. Haven’t you been wanting to do this since reading Anne Carson and Mary Ruefle?

Start with a title that does the work of framing. For example, here are a few titles inspired by Philip Metres' craft essay, "More Than Just A Pretty Hat": Title that cat calls the form of your poem. Title that whistles. Situating title. Title from 4th Dimension. Title of poem I wish I had written. Title with an American word in it. On luminous mystery Etc. Title that is a question. Title beginning with an ing verb. Title after song. Title made from two titles with or between them. Title with its finger on the trigger. Or write a list poem of possible titles that ends in a childhood memory.

An epitome (/ɪˈpɪtəmiː/; Greek: ἐπιτομή, from ἐπιτέμνειν epitemnein meaning "to cut short") is a summary or miniature form, or an instance that represents a larger reality; also used as a synonym for embodiment. An abridgment differs from an epitome in that an abridgment is made of selected quotations of a larger work; no new writing is composed, as opposed to the epitome, which is an original summation of a work, at least in part. Choose five books and write an epitome about each one. Limit yourself to a page of text, whether prose or lineated.

Write an abridgment of a book written by a neighbor who doesn’t exist. Play with how to list the quotations. The title will do a tremendous amount of work in creating context for this poem.

“Epitomacy” means "to the degree of." Write a poem that includes: an uncommon hue of blue, a mathematical formula or a paradox, a dead relative, water (in whatever form), and the word epitomacy. You can use it in the title and leave it out of the poem, or you can bring it into the poem.

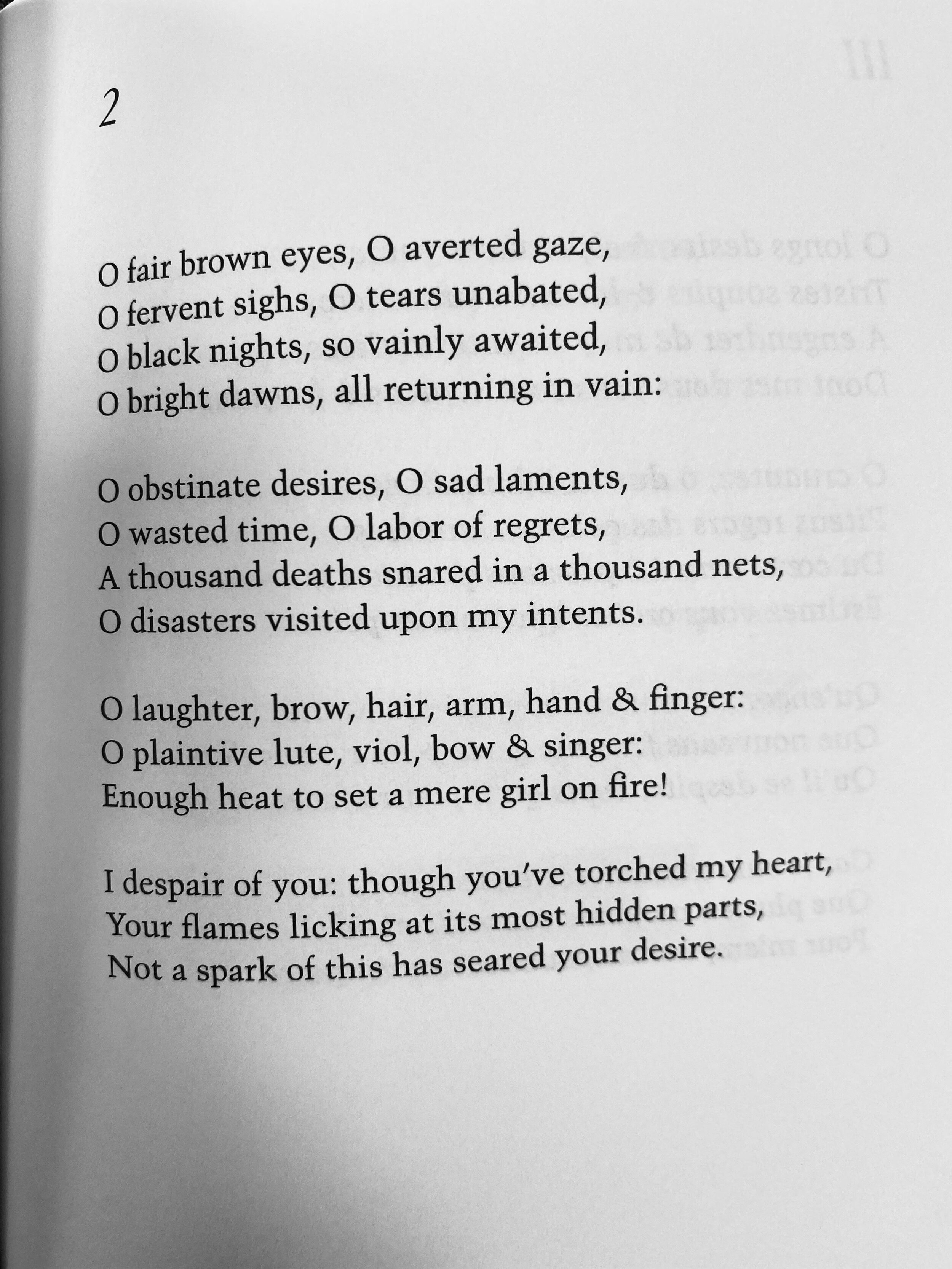

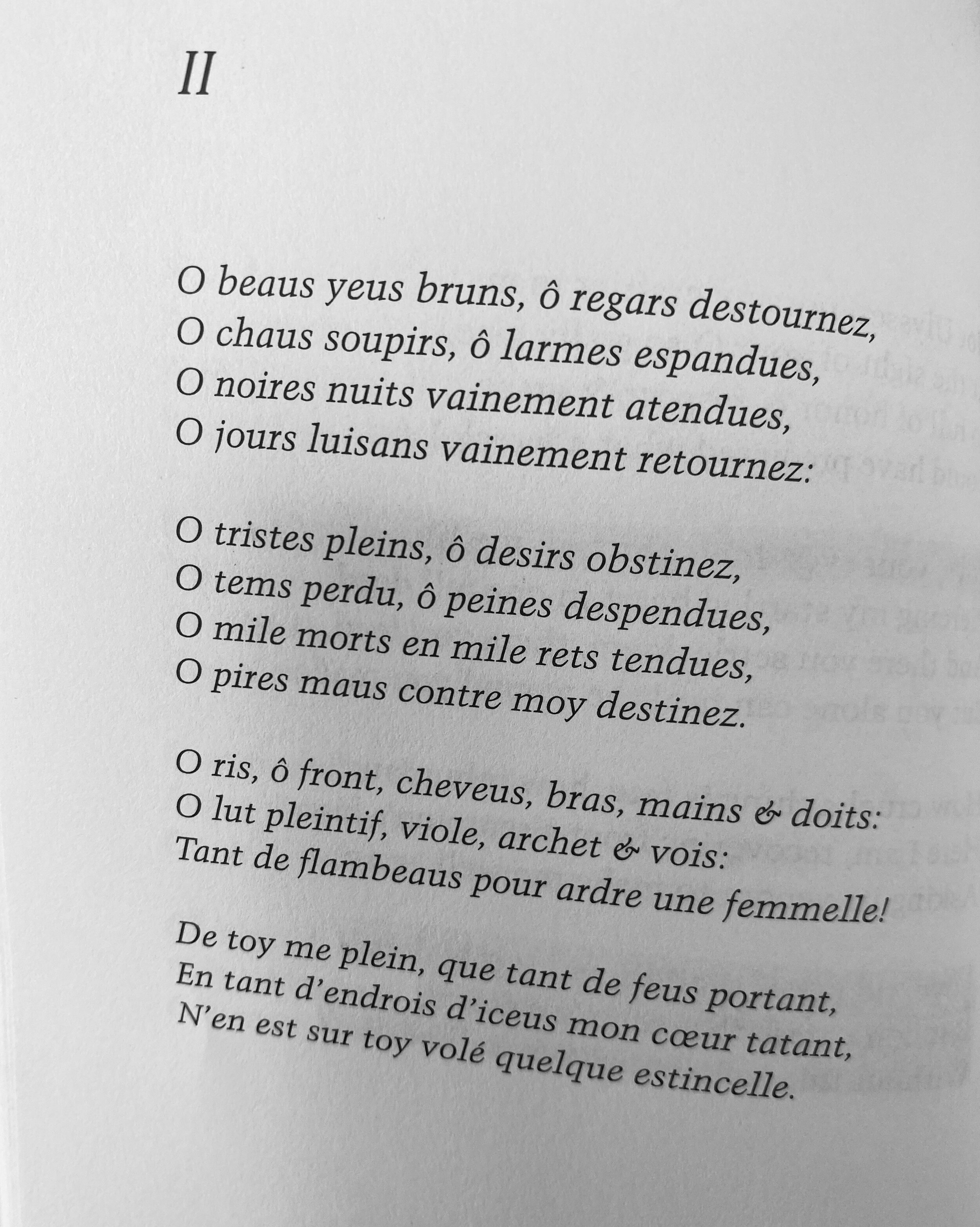

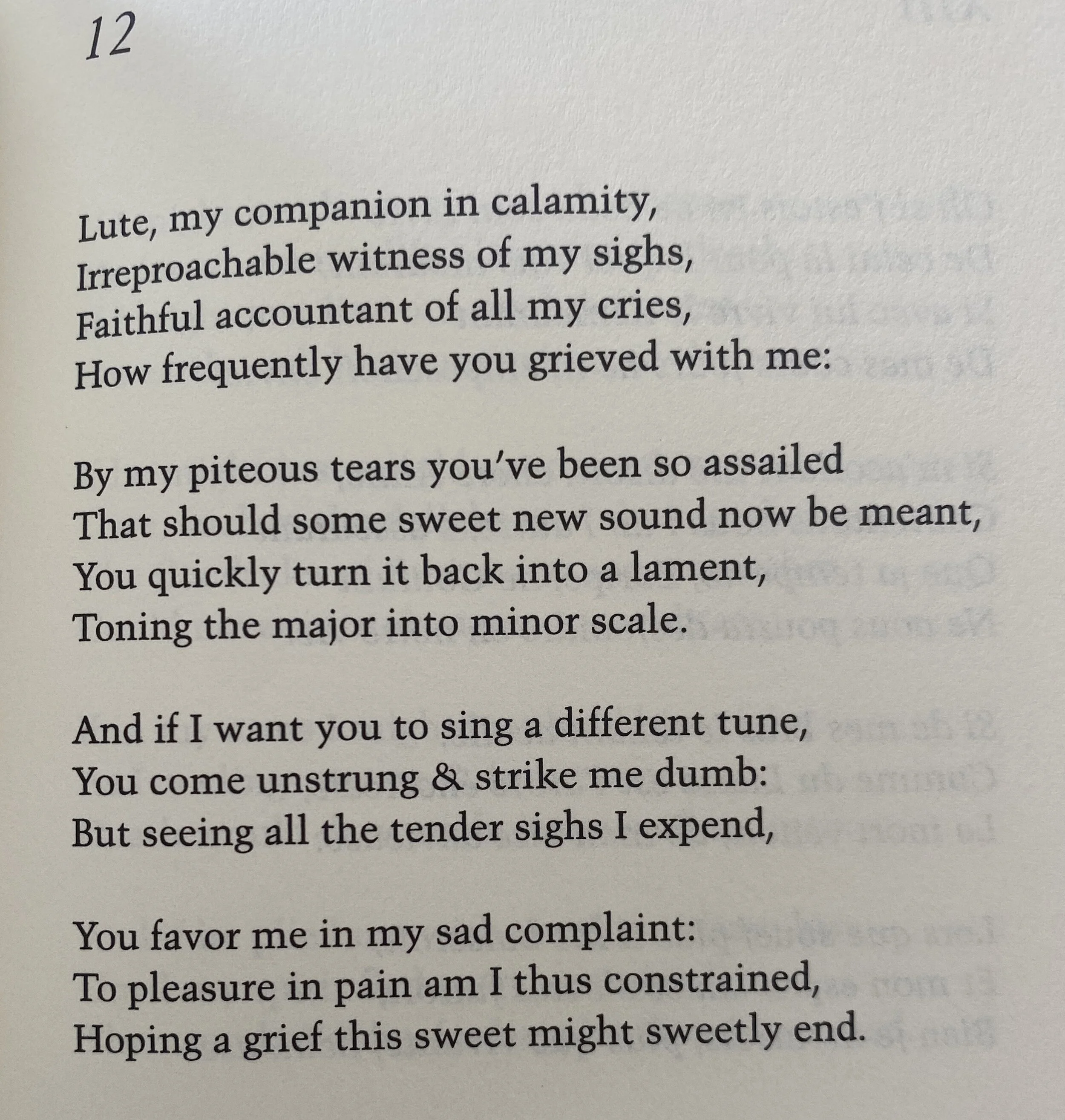

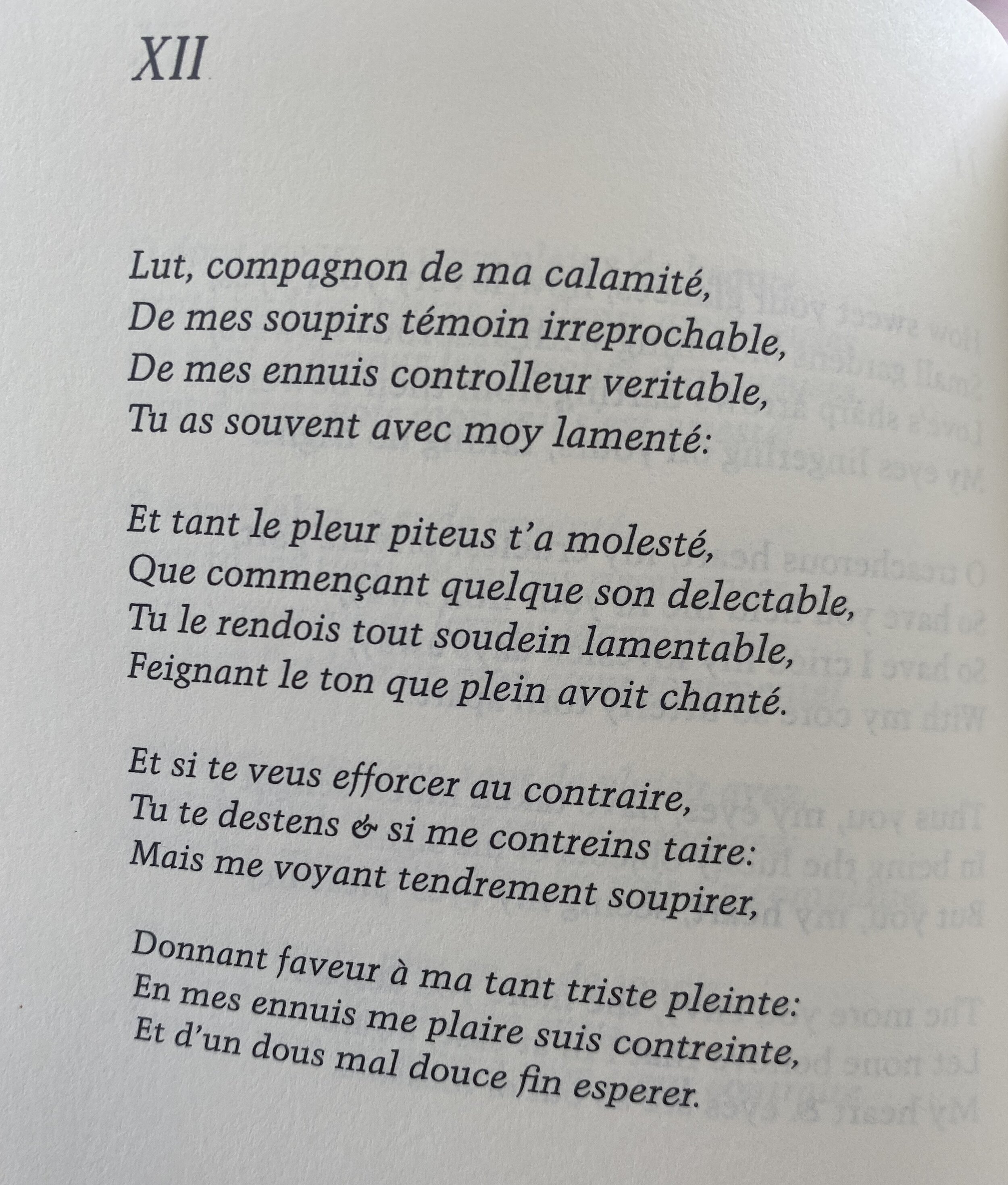

Write a blazon. Then write a counter-blazon addressed to the lover’s pony.

Why not try the cameo form invented by Alice Spokes? Pick a small worthy of a cameo. Or keep a list of small things which deserve cameos and choose three of them to work on.

Write a poem of praise for an ordinary day that lists its beauties — anything from litany to inventory. See Afua Ansong's "Saturday, Like This" for inspiration.

A curio cabinet is a space of access to nostalgia, a jumping-off point towards strange juxtapositions. Spend some time exploring Geoffrey Nutter's compendium and then select a few pieces to combine in a poem that uses a second-person narrator.

Arthur Rimbaud fell in love with Paul Verlaine, and got shot in the wrist by him. Then saw him go to jail for it. What is love in poetry? It is blood. It is the blood of the words and their gauntlets. Write an ode to a particular gauntlet love has left in one’s path.

Write a list poem of love gauntlets. Include fine art paintings and pop-culture movies for referents.

Read “Anxiety” by Frank O’Hara, and write your own response to it.

Knowing how to bring the bend of a blue note into a line break is astonishing. The reader can't unhear it in Carolyn Oliver's "Listening to Ralph Vaughan Williams on a Tuesday Night." Edit an old poem with an eye to bending a blue note. Or write a poem while listening to a favorite blues song.

Read “Making Love To Myself” by James L. White, and write an epistolary poem to White’s speaker.

Read Beth Gordon’s “Elegy With Flying Tires” and use it as model or prompt.

Read Sylvia Plath’s “Sheep In Fog”. Select a line from this poem to begin your own poem. Use Plath’s stanza-lengths as a constraint.

After reading Yannis Ristos’ poem, “Broadening”, free-write ten images that the word "broadening” elicits. Then select a few of these images to build into a poem that includes a landscape altered by climate change. Don’t write images related to climate change landscapes—let tension emerge from the weird juxtapositions.

Tug-of-war is a time-honored American game that originated in England, where two captains were appointed for this game, and they took turns choosing partners and team members until all present were equally divided. We play division. A line is drawn or scratched on the dirt’s surface. The object is to draw the other over the line. The game isn’t over until the entire party has been pulled over. But one cannot let go of the line. To be a team player means to never let go of the line. Write an instructional poem on how to play tug-of-war in a corporate workplace. Use the grammar and syntax that speaks to a child audience. Evoke your own sensual memories of childhood tug-of-war to create tension in the voice and to dislocate the narration.

Dietrologia is the Italian word for the science of what is behind something, what is behind an event. Write one. Use neologisms.

Read Philip Metres’ essay, “In the Den of the Voice,” and write a persona poem from the perspective of Dimitri Psurtsev. Or pick a descriptive paragraph to create an erasure from it.

At the top of a blank sheet of paper, write the following title: “This is for me to say since the old times." Then add a note attributing this title to Diane Williams’ short story, "Tureen". Now write the poem.

“There is a man trying to remember his life / as a single incident and a few words.” Use these two lines from Mary Ruefle’s "The Blue of October" to recreate the man and the memory. Limit yourself to 7 lines, and the single incident should appear in the fifth line. See if the final line can consist of three words with commas between them and no prepositions.

Write a poem in response to Saidiya Hartman’s incredible "The Plot of Her Undoing." Borrow the first clause or just the conceit. Make sure to attribute it. “The undoing of the plot begins when everything has been taken…..”

The image of the seraph below is from medieval book of hours. Explore the iconography collection in The Morgan Library and Museum and see if any of them deserve a poem portrait. Or a litany. Or a ballade.

Using the ridiculously long list of angels [see below], write a poem that invokes a non-canonical angel. Note that many of these angels are also considered demons, which is why they live outside the canon of acceptable angels.

The poem encounters Harahel, the angel of archives, in a gym. Why?

The poem invokes Rochel, the angel of lost things, in a strip mall parking lot. What is missing?

List of Angels

Nadiel, the angel of migration

Poteh, also called Purah, angel of forgetting and oblivion

Artiya'il, remover of grief

Baraqiel, guardian of lightning

Cassiel, archangel of solitude and tears

Israfil, archangel of music

Kalka'il, who oversees the fifth heaven

Lailah, angel of night and conception

Nakir, angel of death and guardian of the faith of the dead

Pahaliah, throne of virtuosity

Radueriel, angel of song, leader of heavenly choirs who can create lesser angels with his mouth

Raziel, keeper of secrets

Sandalphon, protector of unborn children

Purson, fallen angel who rides a bear and carries a viper and knows the past and the future

Mach, who can make you invisible

Shateiel, angel of silence

Ridyah, angel of rain

Rochel, angel of lost objects

Satarel, guardian of hidden things

Abuioro who reveals rare books if requested

Aftiel who governs twilight

Almiras who teaches invisibility

Amaliel, angel of weakness

Andas, the angel of the air

Ardarel, the angel of fire

Barachiel, angel of the altitudes, guardian of lightning

Naamah, angel of prostitution

Harahel, angel of archives

Rahardon, angel of terror

Balberith who notarizes pacts made with the devil

Temeluch who cares for babies born from adultery

Radueril, angel of poetry

The Angel of Clouds who has no other name

Gazardiel who oversees the rising and setting of the sun

Azarel who writes the names of the born and the dead in a book named eternity

Belial, angel of darkness, angel of the earth, also known as Satan

Cerviel, angel of courage

Chosniel whose dominion is human memory and who assists in passing examinations

Dumah, angel of dreams

Ebuhuel, angel of impotence

Eirnilus, angel who rules all fruit

Sulphalatus, angel of the dust

Flaef who rules human sexuality

Fromezin, angel of the second hour of night

Gabuthelon who will govern at the end of the earth

Gagiel, angel of fish

Hamal who rules the waters

Harbonah, angel of destruction and confusion who drives a donkey around the cosmos

Israfel, angel of resurrection and music

Jazar, angel of the seventh hour of the day who can create love between two humans

Jeliel whose name is inscribed on the Tree of Life and who inspires passion among us

Lumiel, angel of the dawn, angel of the light, also known as a Lucifer, and misunderstood for centuries

Mahzian, angel of eyesight

Miniel whos name, when invoked, can induce love in a frozen maiden

Mumiah, angel of longevity and science

Nahaliel who rules creeks and streams

Narsinah, angel of heroes and heroism

Orifiel, angel of the apocalypse, among the angels of creation, ruler of wilderness and untarnished landscapes

Otheos, guardian of hidden treasures

Tablibik, angel of fascination

Tahariel, angel of purity

Tezalel, angel of fidelity

Theliel, angel of love

Tubiel, angel of small birds who heals broken nests.

Yurkemi, angel of hail.

Zachriel, angel of memory, angel of surrender.

Zahun, angel of scandal.

Zianor, angel who gives artistic talents.

Zikiel, angel of comets and meteors.

Zi'iel, angel of commotion.

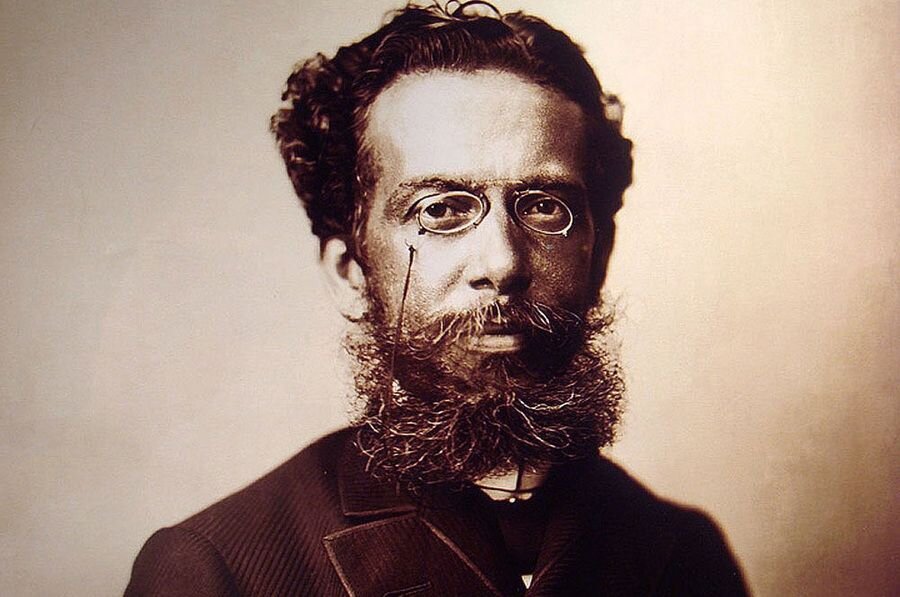

W. G. Sebald's emigrants and APSTogether.

I love #APSTogether, so I couldn’t resist reading W. G. Sebald’s The Emigrants (translated by Michael Hulse) along with Elisha Gabbert this month, and because it helps to keep my thoughts in one place, I’m doing so here. You can still join or dive in…

“Dr. Henry Selwyn”

Dr. Henry Selwyn is "a kind of ornamental hermit" to the garden of the house owned by his estranged wife, Mrs. Selwyn, also known as Elli, a sharp businesswoman. The ruined tennis courts, the things "fallen into disrepair" for lack of use or context, pick up the theme in Sebald's work. One sees the things fallen into disrepair as an extension of their marriage, which has long been uninhabitable.

A mystery: what Sebald calls an "annihilating verdict" on our lifestyles follows Elli's simple remark that the bathroom "reminded her of a freshly painted dovecote."

The servant, Elaine, is the house's only full-time resident, since Mr. Selwyn lives in his hermit house and Elli is often away on business. Elaine is alienated from the outset; Sebald compares her short hair to that of inmates in asylums, bringing both carceral systems and madness into the room. Although no food comes out of the kitchen, Elaine seems to always been there, doing kitchen work, being invisible. The "shadows of servants" roam behind the walls, and Sebald senses them, saying the employers should fear "those ghostly creatures who, for scant wages, dealt with the tedious tasks that had to be performed daily."

*

A fragment from “Dr. Henry Selwyn” puzzled me to distraction: it felt significant. In this fragment, Sebald describes a chateau he had visited where “two crazy brothers had built a replica of the facade of Versailles”, which Sebald described as “an utterly pointless counterfeit.”

What does it mean for a facade to be counterfeit, given that a facade is, by definition, not an original, and therefore counterfeit? I wondered if this was a question of translation, although it felt like a reflective space, a Sebaldian tourniquet that contains others.

In 1939, Benjamin Péret published the essay, "Ruins: Ruins of Ruins" in a small surrealist journal. It is hard not to imagine that Sebald read this essay at some point, hard not to find a similar surface when Péret speaks of ruins as serial - "One ruin drives away another, the one that preceded it, killing it."

A few paragraphs later, Péret adds:

Revolting Versailles, incapable of producing a ruin because it is bereft of ghosts it couldn't give rise to, is as opposed to the ruin of the Middle Ages as the waterfall is to the electricity station. Enemies to the death because the first is killed by the second which springs up from it.

Doesn’t this evoke the counterfeit ruin of the Versailles facade built by the two crazy brothers? Peret moves towards articulating an aesthetic of ruins which feels kindred to themes in Sebald’s own work, and “Dr. Henry Selwyn” seems to be in conversation with this essay, or with Péret’s discrimination between ruins, which he takes the medieval ruins as “fresh” while Versailles is “degenerate”, suggesting that one ruin has some form of life in it while the other remains uninhabitable.

Unlike the Goths or Romantics, Péret doesn't read sublimity into the ruins so much as decay and wreck. Since leaving the womb, man seeks a castle, a cave which his image can haunt. The death gesture is "another castle, a ridiculous bogey....built to the scales of the worms that gnaw him." As for man, he is "a ghost for himself and the castle visited by his own ghost." I hear Elaine in the kitchen, and wonder what Elli’s name was short for— and whether it was Elaine, shortened to Elli to distinguish and set the two women apart?

Again, the empty house and servant ghosts come to mind when Péret describes the silence of the oyster or snail as something which man covets and envies. Man covets the safe shell straight into the "hideous suburban villa" of the "pathetic petit-bourgeois". (*I'll be darned if Bachelard isn't implicated in this.) To quote Peret again:

The dog born of a dog barely recognizes the wolf's ruins, but those of the tiger are for him no more than a trace in the sand, this sand whose ruins he has forgotten, derisory images of those he fails to recognize.

Haunted by "the phantoms of his childhood", man seeks answers from excavated origins. "There is nothing in that childhood to disown, except by someone who has become unworthy of it," Péret suggests. Sebald's characters are somehow unworthy of those childhoods, aren't they? Or that is how they see themselves-- as Germans who are unworthy by association, by affiliation, in relation to the origin they have claimed?

Thus "Stalin tries to make Lenin a dead ruin, the better to betray him." And Peret suggests that poets throughout history have fed on the execution, on the sepulchral death mask of a ruined man, on the corpse who can no longer speak. But in the museum - and in literature - "One ruin drives away another, the one that preceded it, killing it."

Going back to the “freshly painted dovecote” that replaces the hothouse: is Sebald taking this as a counterfeit Versailles facade? Is that why it’s an "annihilating verdict”?

"I have never been able to bring myself to sell anything, except perhaps, at one point, my soul," Henry confesses to Sebald, without expanding on this Faustian bargain. We are left with Henry’s suicide, in the small house he called his “folly”, in the garden of the wife and nice life from which he remained estranged.

Cape Varvara

Sebald alludes to it on page 129 (“into the wings of Cape Varvara with its dark green forests, over which hangs the thin sickle of the crescent moon”). The closest thing I could find was Varvara Village on the Bulgarian coast of the Black Sea, which seems distant from the boat trajectory in the text, and yet, it has it’s own ghosts. On the south side of the beach, there are rocks known as the Dardanelles, beloved by divers. Currently, the village has 250 residents. More from wikipedia:

In the middle of the 19th century, the site of the modern village was uninhabited, except for the small monastery or chapel of Saint Barbara with holy springs, after which the village was named. An older settlement may well have existed, as indicated by the marking of the name Vardarah on Max Šimek's 1748 and Christian Ludwig's 1788 map in that area. Until the Balkan Wars, Varvara was a small Ottoman village of ethnic Turkish refugees from northern Bulgaria who settled there following the Liberation of Bulgaria in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78. After 1913, the Turks moved out and were replaced by Bulgarian refugees from Eastern Thrace

The village is best known for its intellectual community of artists and writers. Many young artists came to Varvara in the 1970s and 1980s and populated a small camp called The Sea Club which the Academy of Arts in Sofia had purchased for them. Over the years a larger group of artists established themselves in Varvara and started to buy real estate and build a small community.

Kissingen

The narrator strolls the grounds of Kissingen looking for answers about Ferber and Luisa Lanzberg. He sits to read the local newspaper, and finds:

The quote of the day, in the so-called Calendar column, was from Johann Wolfgang Goethe, and read: Our world is a cracked bell that no longer sounds. It was the 25th of June. According to the paper, there was a crescent moon and the anniversary of the birth of Ingeborg Bachmann, the Austrian poet, and of the English writer George Orwell.

Again, time is told by the moon—the crescent—which reminds me of how critical theorists have spoken of the end of the village, and how Sebald haunts those spaces, inhabits the ghosts, and so telling time by the moon, or using it as a form of location, is antiquated. It feels out of time. Even as it establishes time and temporality.

An Archaelogy of Nightmares

an excavation inspired by twitter

*

Jeff dreamt he could not stop screaming at the students. Then he dreamt he could not stop screaming. Then he dreamt he could not stop. Then he dreamt he could not. Then he dreamt he could. Then he dreamt he. Dreamt he was. Dreaming.

*

Lori dreamt she had to catch a flight in an hour but she couldn’t find her passport, nor had she packed for shit. There was someone flying an airplane she needed to board, and someone else cleaning their car so it would look nice when they picked her up from the airport later. Lori looked under the mattress for the passport as she had see someone do successfully once in a movie, but there was no passport or suitcase under the mattress, only a bread knife.

*

Dolfi dreamt that they had stolen a toy from a boy who stood near the metal gate, waiting for the toy to return. But the theft made the toy unrecognizable to the boy. That one is not mine, the boy said, small and strong. He refused it.

*

J. D. dreamt of many connecting rooms, an effort to exit, the word exit, itself, an effort; the many so hyper-connected. The more the merrier it was not.

*

Jennifer dreamt she was in a familiar place, but the door would not open. When she sought a more familiar place, she realized the corridor was going the wrong way. She opened a door and there was a terrible thing in a chair, waiting.

*

Michael dreamt of an escalator without a handrail in a mall where the shadow-people hovered near windows, casting their horrid silhouettes against the interior walls, at the treelike in is grandparents’ garage, where all the old trees lived at night, where they plotted the end of humanity in a grey, cold dusk: the color of missing rubber handrails.

*

Lisa Marie dreamt she was trapped in an elevator with the realization that she would be trapped in an elevator soon. At some point, the doors would not open. There was no way to predict when that point would begin, thus transforming a point into a line, a mutant moment which acquired its own momentum and demand for resolution. She wanted it to end in the dream. Sometimes bugs arrived. Sometimes bugs ran beside her as tried to catch the flight she kept running late for. The point kept extending itself into a line.

*

Math dreamt the curtain was rising on opening night, a dimming, the absence of script in his mind meeting the audience’s expectation. While it is common for actors to dream that they won’t know who they are playing when the performance begins, it is very rare for puppeteers, or the voices which emerge from inside a hand.

*

In Ed’s dream, he climbs a tower and encounters three severed heads in the belfry. He knew the belfry was for bats because they lived there in a horrifying story. He wonders what went through his head, or what made him want to climb higher, to this belfry filled with abject horror, in his head.

*

Veronika dreamt herself inside a tower, hiding with others from the apocalypse— realizing the tower, itself, was crumbling, falling apart. To know the end is a nested story inside a story about the failure of nests.

*

Jayaprakash dreamt he was the oldest one at school, but others only knew he was old, and not the oldest, so there was a pressure to keep this extremism secret. He is ashamed to be back, to be among the young and their newness. He hides in a backyard at the school. Weeds hide their feet from the naked concrete under gravel. The sky holds a sunlamp for the newest to shine, to look newer. But he is alone, antique, ancienne-regime as a ruin the students sit on when googling the sun.

*

When Michael S. appeared at the school, it was to dream that he’d taken a class he never attended. And yet he was required to take the exam. He was too old to google the sun and too young to unknown that he was too old to google it, and to know he had skipped things in the past which may have happened when he did things which weren’t studying. He felt guilty for the things he had not done, the things he had done, the things he dreamt he should be doing, the knowing he could have, and nothing.

*

Emma dreamt raging bears had entered the building, their fury occupying hallways. She tried to hide in small spaces and dark corners to escape but the bears followed, all corridors carrying the echos of growls.

*

Lynne dreamt she was on a freeway to nowhere and missed the last exit ramp. Also: the vague scent of Los Angeles or Seattle, train cars and canals, separate.

*

Hope dreamt of snakes in terrible situations where the snakes seemed dangerous, thus estranging Hope from the self who loves snakes in real life. She couldn’t decided which part to fear: the snakes or that self.

*

In Ilinca’s dream, the mossy, slimy stairs can kill her. The weblike attic floorboards won’t support me. Everyone and their mother lies. She knows this because ambulatory buildings follow her around the city. She meets someone who tells her she is herself.

*

Joseph dreams there is a number he must call, urgently. There is also a phone. There is a reason he cannot complete the number, and this reason is related to the phone, the number itself, the pattern of digits, and toilets which are not what you think.

*

Great Aunt Xenomorph dreams of cement blocks with emotional needs. They are so heavy. They are so heavy and the elevator door will not open. There is no magic word, no expiation.

*

Claudia dreams she is crouched inside the clean stall of her elementary church/school barthoom, trying to get away from someone she fears. The pipes above her head are dripping pipes. There are multiple crucifixes painted red by the light from an "exit sign". She is in the woods behind her childhood home, trying to escape again. Something adult keeps interrupting.

*

Nina dreams someone drives up. This person parks outside her house. She knows the person must not enter the house under any condition, so she locks all the doors quickly. Then she locks them again, slowly, dreadfully, as one must when there is no other option. Although she cannot see anyone, she hears someone walking around the house, their shoes crunching the grass, trying to open windows. The hamster who loves the red wheel keeps running in circles around it.

*

Brian dreams he is in second-floor bedroom window looking out over the suburban neighborhood, where he can see soldiers climbing over fences using special equipment, scurrying under hedges like sophisticated mammals. He knows they are coming to kill everyone he loves. He knows because he’s seen it on television, happening to others around the world, and now the world has come to meet him.

*

Ilze dreams a tornado is headed towards her just before the giant wave at the beach swallows her — the reward for having imagined is having it happen. She is in her mother’s house as it begins crumbling to pieces, the floor moving, shifting, splitting open. She has never written about an earthquake. She will not even dare utter that world aloud. Her teeth are falling out.

Photo taken from The Art of Aubrey Beardsley, available online at Gutenberg.

Grotesque or Nothing: Aubrey Beardsley

“I have one aim—the grotesque. If I am not grotesque, I am nothing."

On a recent binge-read Decadents, Neo-Decadents, and Graveyard-Goth poets, I found an old book on my shelves — Aubrey Beardsley: The Man and His Work by Haldane MacFall, published in London in 1928 — and fell in slight love with the awkward necro-romanticism of the introduction:

About the mid-July of 1894, a bust of Keats had been unveiled in Hampstead Church--the gift of the American admirers of the dead poet, who had been born to a livery-stable keeper at the Swan and Hoop on the Pavement at Finsbury a hundred years gone by--and there had foregathered within the church on the hill for the occasion the literary and artistic world of the 'nineties. As the congregation came pouring pitof the church doors, a slender, gaunt young man broke away from the throng, and, hurrying across the graveyard, stumbled and lurched awkwardly over the green mounds of the sleeping dead. This stooping, dandified being was evidently intent on taking a short-cut out of God's acre. There was something strangely fantastic in the ungainly efforts at a dignified wayfaring over the mound-encumbered ground by the loose-limbed, lank figure so immaculately dressed in black cut-away coat and silk hat, who carried his lemon-yellow kid gloves in his long white hands, his lean wrist showing naked beyond his cuffs, his pallid, cadaverous face grimly set on avoiding falling over the embarrassing mounds that tripped his feet. He took off his hat to some lady who called to him, showing his "tortoiseshell" coloured hair, smoothed down and plastered over his forehead in a "quiff" almost to his eyes--then he stumbled on again. He stooped and stumbled so much and so awkwardly amongst the sleeping dead that I judged him short-sighted; but was mistaken--he was fighting for breath. It was Aubrey Beardsley.

British illustrator and author Aubrey Beardsley is known for his black ink drawings that foregrounded the grotesque, the gruesome, the excessive, the decadent, the queer and the erotic. He lived a short and difficult life, committed to irreverence and a refusal to blur the line between artists and persona. Beardsley was eccentric in public and private; he was weird and fine with it. He selected his clothing intentionally, including dove-grey suits, hats, ties, yellow gloves. Arthur Symons qualifies his creative process:

….he hated the outward and visible signs of an inward yeastiness and incoherency. It amused him to denounce everything, certainly, which Baudelaire would have denounced; and, along with some mere gaminerie, there was a very serious and adequate theory of art at the back of all his destructive criticisms. It was a profound thing which he said to a friend of mine who asked him whether he ever saw visions: "No," he replied, "I do not allow myself to see them except on paper." All his art is in that phrase.

After a massive lung hemorrhage at 23, Beardsley converted to Catholicism. His health continued to decline and he died of tuberculosis two years later, in the Cosmopolitan Hotel in Menton (one of my favorite cities on the French Riviera). Following a requiem mass in the Menton Cathedral, his immortal remains were interred in the Cimetière du Trabuquet.

*

Because Haldane MacFall’s introduction to the book is a fireworks of crackly syntax and necro-romanticism, I’ve included it in full below, for those who need a new temporality, a “twelvemonth” in which to exist….

On a side note, Donald Olson has chronicled Beardsley’s decline for The Gay and Lesbian Review, and he attributes the fall his association with Oscar Wilde and the aesthete crew.

*

I appreciated how MacFall captioned some of Beardsley’s drawings with the word “suppressed,” which is not quite the same as “censored.” To me, censor lies close on the tongue to censure, which indicates a punishment, a price to pay for touching the forbidden, whereas suppressed is closer to muffling, gagging, preventing from speaking at all.

Suppression is preventive rather than reactive. Someone drowns when I read it.

MacFall also says Beardsley was “expelled from The Yellow Book” in its first year of publication. Expulsion evokes Edenic imagery, a sense of moral trespass which involves one’s relation to the forbidden.

The forbidden is that which may consume us if we consume it. The forbidden is what gives rise to the need for expiation. Someone must devise a ritual which undoes the anxiety of influence, the peculiar power to taint that characterizes the condition of forbiddenness.

César Vallejo was born in Peru. After being persecuted for his leftist politics, he emigrated to France. His poems speak from the interiority of dispossession, both collective and personal. I am riveted by them.

Three versions of César Vallejo in translation.

César Vallejo’s “Black Stone Over a White Stone” (the title’s literal translation) has been a poetic obsession this year. Like Donald Justice and countless others, I found myself writing from its meridians. Because my variant from that meridian, “On the Death of the Day of the Bear,” is forthcoming — and because I’m in the middle of a translation workshop— I wanted to think aloud about why it haunts me, and how different translators have approached this particular self-elegy.

Here is the original version.

“Piedra Negra Sobre Una Piedra Blanca” by Cesar Vallejo

Me moriré en París con aguacero,

un día del cual tengo ya el recuerdo.

Me moriré en París -y no me corro-

tal vez un jueves, como es hoy, de otoño.

Jueves será, porque hoy, jueves, que proso

estos versos, los húmeros me he puesto

a la mala y, jamás como hoy, me he vuelto,

con todo mi camino, a verme solo.

César Vallejo ha muerto, le pegaban

todos sin que él les haga nada;

le daban duro con un palo y duro

también con una soga; son testigos

los días jueves y los huesos húmeros,

la soledad, la lluvia, los caminos…

*

According to legend, the poem was born when a very melancholy Vallejo strolled the streets of Paris in his black overcoat, and paused to sit on a white stone. This poem moves around this image, a sort of mental monument, and winds up elegizing the speaker’s life with a sort of loose irony that reminds me of Benjamin Fondane, Tomaž Šalamun, Ryszard Krynicki….

It looks like a sonnet. It walks like a sonnet. It turns like a sonnet after the octave, and this turn is a change in temporality, or the tense used by the speaker. I can’t stop palpating the posthumous voice which seems to revoke a post-ness, or a past, by layering time into an ongoing present.

“Black Stone Lying On A White Stone” translated by Robert Bly

In his 1971 translation, Robert Bly titled the poem “Black Stone Lying On A White Stone", and this subtle shift from “Black Stone Over a White Stone” seems to give the black stone more agency: the black stone is lying on the white stone rather than merely existing in a positional relationship over it.

Here is Bly’s translation.

The first line of each stanza is indented; the speaker begins in what seems to be a first-person “I” and uses the future tense, only to switch after the octave, where the envoi begins: “César Vallejo is dead.” It’s possible to read this as an identification with death, with deadness, with an epitaph or a headline. But this poem manages to avoid self-pity—there is something courageous and gorgeous in how it lays out the descriptions without being maudlin.

I don’t feel sorry for the speaker when I read it. What I feel is a sense of existential and ontological respect.

Bly’s translation, like Seiferle’s, puts a negative between the dashes in the third line: “—and I don’t step aside—”. The negative makes the speaker’s voice more passive than it might otherwise sound (which you can see in Andreas Rojas’ version, which translates that line “— and by this I stand—”.

*

“Black Stone On A White Stone” translated by Rebecca Seiferle

Rebecca Seiferle’s translation also does something with the title, namely dispenses with the positional modifier “over” and keeps the black stone simply on the white stone, which sounds less hierarchal, or begins the image without an undertone of dominance.

Here is Rebecca Seiferle’s 2008 translation.

Like Bly, Seiferle preserves the stanzaic structure: two quatrains and two tercets.

Like Bly, she indents the first line of each stanza — though she doesn’t do this in the first stanza, a practice I normally associate with prose (i.e. leaving the first paragraph unindented and beginning indentations with the second paragraph). Maybe the self-elegy plays into this choice, or maybe the translator wants to begin with a more anchored I, a more assertive first-person that will increase the impact of the shift in “I” across the poem.

In the translator’s note, Seiferle says she gave up the metric form of the original (a hendecasyllabic count, except for line ten) in order to keep the the language and images, or permit the interruption of time in grammar to be louder than the interruption of time in form.

I thought it interesting that Seiferle’s translation is the only one of the three to not use “Everyone beat him” in the third stanza, choosing a lowercase “they kept hitting him” which isn’t entirely in past tense but closer to something ongoing. “Kept” also feels talismanic here, as something the poet “kept”, or something which creates a fascinating relationship with the “witnesses” of the final stanza. Witnesses keep things they have seen; witnesses are the keeper of visual events, and in this poem, the witnesses are not humans — they are objects or abstract states or segments of time.

To me, Seiferle’s translation inflects the white stone, or draws back to the title in which a rock might speak, or see, and there are monuments in that juxtaposition.

*

“Black Stone Over A White Stone” translated by Andres Rojas

Andrea Rojas titled his translation directly, matching Vallejo’s title word-for-word. The black stone is over the white stone. The positionality leaves us wondering if the black stone covers the white stone, or reduces the white stone’s visibility. We are seeing the black stone, and the physical relationship between the stones is clear from the outset. That kind of clarity in titling provides space for visual subversion later: the obvious begs to be undone.

Here is Andreas Rojas’ translation (from his blog).

Rojas doesn’t indent the first lines (and this may due to technical formatting issues on blogs) but he, too, keeps the stanzaic structure. What I value about this translation is its proximity to a direct, word-for-word model that allows one to see the bones. Describing his translation as “inelegantly worded”, Rojas explains his choices:

I am told the 10th line should properly read “without HIS doing anything to them.” I almost instinctually translated it as “without HIM doing anything to them,” and that’s how I’ve kept it for the clarity the “wrong” usage affords.

My solution is inelegantly worded, but it conveys both meanings Vallejo implies with his switch from the past tense (“le pegaban”) to the present tense (“les haga nada”): they beat him “without him doing anything to them” to cause the beatings and “without him doing anything to them” after he was beaten. Since “he” is dead now, impunity for prior beatings is guaranteed. Vallejo’s shift in tense also implies that the beatings were carried out with impunity even while “he” was alive.

He focuses on the double-meaning of the poem’s last word, “casinos”, often translated as “paths” or “roads”:

In Spanish, however, “camino” also means “a journey taken from one place to another.” (See the Royal Spanish Academy’s Dictionary of the Spanish Language, definition 3). I have translated “caminos” as “journeys” to capture the broader meaning I believe Vallejo intended. The same translation is possible in at least one other Romance language: “Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita” (“In the middle of the journey of our life”).

*

What James Wright said of Vallejo, in the way that only Wright could say things, along that blade of love and despair which drew him to other poets, and led him to memorize their poems, to preserve them as talismans, feels true to me. I leave you with his word:

“I think he is one of the greatest poets in any language I know of. There is not a single poem in which any human being is treated with irreverence. There are a great many poems in which death is hated and fought. And it is fought back, not by some vague 'spiritual value'. It is fought back by Cesar Vallejo, lying sick in a charity hospital, dying of hunger and fury.... As a poet, he perpetually took a direct part in the creation of his own identity. He turned his back on the marketplace; he denied the popular press is right, and the academic community is right, to judge the imagination by standards that have been comfortably dead for a hundred years; he was true to his inner self. He was a dangerously religious man.”

The lovely contrary in Kay Ryan.

1.

Reading Kay Ryan’s Synthesizing Gravity: Selected Prose, one is struck by the note on the back cover:

“A jewel. Beautifully articulated.” (Patti Smith, from Instagram)

One is, of course, delighted to see Patti Smith lay one of Ryan’s favorite complimentary words—articulated—to rest on a social media grave that it may travel like an everlasting silk buttercup to grace the book’s cover matter.

As for the essays, themselves, one appreciates the continuity of Ryan’s contrarian keynote— as if she put her foot on the sustain pedal and loved the sound so much she could not let go for an instant—“The whole ball of who we are” brought to bear on the downstroke. The performer’s commitment to tone at the expense of dynamics is remarkable; it would ruin a lesser poet or pianist.

That’s the uncanny part: the way Ryan’s prosodic voice leans on the experience of marginality, or a view of the self an Unimportant Poet which is at odds with reality. Perhaps this sense of alienation is tied to her experiences as an LGBTQA person in California, or maybe it’s just the soil of a certain Americana.

In “Con and Pro,” Ryan draws an exclusive circle: “My poets are a dryish people. Lonely, and what of it. They don’t gather round a campfire.” This circle doesn’t include Walt Whitman, whose “big stride” is too “bulky” and “all-encompassing”… “I like skinny-bodied poets, the stringy ones who don’t impress the boys on the beach,” she writes. The shape of the poem, its body, is an aesthetic matter for Ryan, and she likes them lean.

Nevertheless, Ryan’s story of literary origins is as American as it is heartwarming. She and her partner, Carol Adair, taught for over thirty years at a small community college in California. While serving two consecutive terms as U.S. Poet Laureate, starting in 2008, Ryan used her platform to champion community colleges. If there is a prestigious, literary financial grant, Ryan has won it. President Obama awarded her the National Humanities Medal. By 2010 (the year she won a MacArthur Genius Grant), Ryan had published no less than 25 poems in the New Yorker, averaging a rate of two New Yorker poem-pubs per annum since 1995. If this isn’t a sign of being among the Established, one might wonder if establishment even exists.

In her own words, Ryan remains a “whistle-blower,” “an advocate for underpraised and underfunded community colleges across the nation”:

“I was reluctant to think of myself as a writer because it required a kind of emotional exposure that I didn’t want to commit to. I never liked the image of the poet, and I still don’t to this day. There is something way too romantic about it, and way too emotional and way too posturing. I come from clean-scrubbed people who would be embarrassed by that.”

In the words of others: “Ryan’s compact poems – which have been compared to the short, humorous piano pieces of composer Erik Satie and to Faberge eggs – are typically less than 20 lines long and her lines often contain fewer than six syllables.”

2.

The fear of being influenced by literary trends comes up in everything from her surly, lovely gripes about AWP to her writings about other poets. Anxiety of influence is present more as a systemic fear than a nuanced, particular one, and in this concern, one senses a fidelity, a first principle.

Poetry, for Ryan, is "this impossible pang" where the poem, itself, functions as a "trap — that is a release." It enables us to enter a room filled with treasure — a room available whenever we choose to enter it —but we can take nothing out. We don't go home with a receipt. The experience of the poem is singular, even when repeated.

As to whether she considers her audience, Ryan nods. Of course she does—and doubly. One part of her hopes they will sit up in their graves:

“I am at the table of the gods and I want them to like me. There I've said it. I want the great masters to enjoy what I write. The noble dead are my readers, and if what I write might jostle them a little, if there were a tiny bit of scooting and shifting along the benches, this would be my thrill. And I would add that the noble dead cannot be pleased with imitations of themselves; they are already quite full of themselves.”

The other part plays the poetry game, and “seeks good journals for the poems and good presses for the books, accepts reading dates and agrees to interviews, so that the poet might gain name recognition, by means of which the poet's poems might reach an audience and rise or fall fairly, based upon their merit instead of simply resting upon the bottom because nobody ever saw them.”

3.

Ryan often begins an essay by clarifying the essay was solicited. She writes about walking because an editor asked for her thoughts on poetry and walking. Hence, a brief essay on walking appears. Ryan describes a poetics of peripatetic observation, noting “the brain anticipates significance; it doesn’t know which edge may in fifty yards knit to which other edge, so everything is held, charged with a subliminal glitter along its raw sides.”

Ryan writes against notebooking with the toothiness of a brilliant marketer generating buzz for the scandalous surprise of posthumous notebook publication. The problem with note booking is Kodak, or the Kodak moment which develops memory a certain way, rather than allowing memory to return and mingle and exert subterranean influence. Her concern circles "the memory that might result from repetition." The details of the snapshot are less compelling than the "long way of knowing,” and "we must be less in love with foreground if we want to see far." Not for her, the spicy art being devised by those who take photography as a disruptive medium. Not for her, the Barthesian punctum. Notebooks enact a "dangerous piety" of preservation. They are religious in their remembering, and this religiosity tends to sanctify the notes. Loss is a gift which enables finding and discovering. Loss, for Ryan, is part of life.

Although she isn’t one for notebooks on principle, Ryan certainly reads them. And reviews them — she prefers Robert Frost’s poems to his notebooks or his biography, noting that “the main thing one discovers in the notebooks is Frost's great fidelity to himself.”

Source: “Kay Ryan rises to the top despite her refusal to compromise” (Marin Independent Journal). By refusing to compromise, does this mean teaching at a community college rather than a state college or a private school? How is “compromise” defined on the American poetry scene? I hope someone intransigent and dedicated has written an essay on this.

In an essay on nonsense and slant, Ryan uses Edward Lear's "To Make Gosky Patties" as a slant ars. She lists the elements which are unique to this poem, and to poetry more generally (though certainly this is true for certain kinds of poems more than others). Among them:

"An invented goal”—because no one actually needs gosky patties; no one even imagined a need for them before this poem..

"Cowbird technique" — The Cowbird lays eggs in another bird's nest and borrows the form of it. " Nonsense isn't shapeless"… it comes to us in order forms, rhymes, limericks. "You can tell real nonsense from garbage because nonsense is shaped and tense."

“Exactness.” “Incongruity”. “Awkward proximities.” “A sense of immience” — the build-up towards a sneeze, that sense of a game underneath. “A highly personal idea of cause and effect,” which is to say, relationships and time. “The reader made into co-conspirator.” “A perfect absence of sentiments.” “ Indifference to outcome.” “Frustration of ordinary expectations.” “A wonderful sense of helplessness.” A modified glee. An object which resembles delight.

4.

Confession: Ryan’s essay on AWP was my favorite. It begins in the key of not-for-me (a key I know intimately), the drizzle of schadenfreude one expects more from minor writers like myself than major ones like Kay Ryan.

Let it be clear: not for Ryan, the academic conferencing and inner circulariums. Not for Ryan the movie set, the theatre, orchestral music, team sports, the migraine sure to appear alongside a crowd. Instead, Ryan will have “the solitary, the hermetic, the cranky self-taught…. the desert saints, the pole-sitters, the endurance cyclists, the artist who paints rocks cast from bronze….” She will have the metaphysical in plain language without extra pickles, hold the mayo.

How she ends up at AWP is simple: she was “invited to attend as an outsider, and to write a piece for Poetry.” How one can be an “outsider” while serving as US Poet Laureate is never explained or expounded upon. Presumably, all American poet laureates get to wear the tremendous laurels while also maintaining an excited foot or steed in the Outsider-Poet stable. A poet laureate may be under-recognized, under appreciated, and under-funded but they are also as Inside as one gets. It’s important to recognize that so that words continue to have meaning. Pyramids aren’t expressions of belonging—they are material, physical objects whose definition isn’t related to emotional events.

Planning to go while retaining her “alienation,” Ryan acknowledges this fun is only possible due to her “age,” defined as the time when one is no longer young and unpublished. Although Ryan conflates poetry prestige with age, assuming that all poets start young, get their degrees, and ripen into fruition, one is tempted to overlook it, as one must overlook such conflations regularly in certain circles. One overlooks such things because the skid-marks are familiar. “Maybe I would never have been influenced, as I feared I would, but to this day I believe I needed to guard against something, even if that something was imaginary,” Ryan writes.

“The most important thing a beginning writer may have going for her is her bone-deep impulse to defend a self that at the time might not look all that worth getting worked up about”—certainly all of us have been there, staring at the shape of the ice pick which masquerades as a migraine in a room where no one speaks your native language and editors, like all of humanity, struggle to balance calls from ailing kids with the demands of the book fair.

"Simone Weil would have starved herself to death before she would have gone to AWP," Ryan announces.

“But you lost the opportunity to stay as pure as your idol by having kids,” my husband reminds. And he is right. Like Weil, I love humanity so much I can’t help being infuriated by humans. Unlike Weil, I am beholden to more than my ideals, my hopes, my life.

O, that level of moral purity - impeccable, impossible, and unlivable, how I miss it! How I mourn the way motherhood revokes it. I was so pure before looking young mammals in the eye and swearing that ghosts would not hurt them. My commitment to nonsense outweighs any credible moral claims I can make about the universe, but I long to be that clean again, to be abominable as the white cartoon snowman.

Reading Ryan is like seeing myself in the mirror of my own Puritan peccadillos — minus the magnificent fellowships, awards, and prizes, of course, and the laurels of official Outsider Poet status.

5.

If I keep trying to understand Ryan’s see-sawing between Poetry-As-Nonsensical-Delight-Raft and Poetry-As-Space-Of- Moral-Purity, it’s because she is serious about seriousness, yet conflicted about self-reflective writing.

There is an anti-confessionalism current in her poetics that seems related to notebooking, a logic the says the mirror is the mirror but only the poem which pretends not to be a mirror is a good mirror. I wondered if it was the seriousness, the open-handed earnesty of notebooks, which makes them distasteful or decadent? Remember what happened to punk in the late 90’s— how the divide between the unaffiliated decadent and the identitarian straight-edged kept simmering below the surface until we fell in love and sold out and resurrected to find Trump got elected as the most hardcore members of our former punk coteries unveiled their Proud Boy flags on social media?

This is not to suggest Kay Ryan is punk but, rather to trace the tonal defiance, the countercultural opting-out, which can robe an ontological puritanism,and which starts off in the tempo-marking of punk, shooting a bird at the sunshine happy posters that lie from the walls of school hallways. I have no conclusions to draw that aren’t self-indictments, and maybe I’m looking too hard at a point which wants to be a line, as one is inclined to do in a notebook.

Despite the anti-sentimental keynote, Ryan raves about Milan Kundera’s prose, particularly his view of forgetting as a form of remembering. There’s also a fantastic section on Tantalus (page 106), and a moving, inspiring story of poetic origin (page 114). There are warnings, sirens, injunctions, and permissions. There is so much one can say about Ryan that I prefer to end without saying it—not because “my people” were “clean-scrubbed”, but because my people are complicated, messy, raucous, known for their tonal thickness.

I loved Kay Ryan’s prosodic company for its consistent contrary-key, and the She insisting upon it. Even though Robert Frost is not my hero, I loved reading her rapture. It is instructive to study the pantheons of wonderful poets because humans are more interesting and thoughtful when describing what they love than when ranting about what they hate.

Ryan mentions "the hot thing" in poems—the things which can burn us or start fires, those with the potential to combust or illuminate. One cannot make a poem if one removes all the hot things, since "it is the job of poetry to remain open to the whole catastrophe." And I love this as a note on revisions. I wrote it down. I refused to forget it just in case I could use it or share it:

When revising, look at the poem. Find the hot thing. If there is more than one hot thing, how do they relate? Are they even related? Are both needed? Honor the hot thing/s by not asking them to carry too much - give them space to breathe. Remember, a conflagration needs air, oxygen – and that space around it is part of the weight, part of what creates the possibility of fire.

Too many fires in one poem makes leaving the room easier. Or, if one wishes to make the leaving easy, then be sure to use direct address, as Ryan does in “Blandeur”:

Unlean against our hearts.

Withdraw your grandeur

from these parts.

And don’t be surprised if posthumous notebooks appear. I, for one, look forward to sitting in a meadow with a cold beer and all the gorgeous contrary that is Kay Ryan doing the thing she said she wouldn't do until someone invited her.

A visual counterblazon which snuggles next to Thomas Campion’s poem, “There Is A Garden In Her Face.”

The poetic blazon (or blazon).

Blason means “coat-of-arms” or “shield” in French. From French heraldry, blason translates as “the codified description of a coat of arms”

As a poetic genre or technique, blason (or blazon) comes to us from 16th century French poet Clement Marot, who penned a poem celebrating a particular woman by listing parts of her body which he then compared to incredible things. Although Marot’s blason anatomique set the standard for blazons to come, its roots come from medieval heraldry, with its iconic representations of families and their attributes. Heraldic devices represented the entire family, or, in some cases, knightly qualities (e.g., the pentangle in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight).

In the blazon, the physical traits of a female subject are catalogued, often in sonnet, sonnet sequence, or love lyric, and described by individual parts rather than the body as a whole, so parts of the body compared to gems, jewels, celestial bodies, sunrise, and various aesthetic glories. Gilded by ornate, eroticized, the "real" woman disappears, and her image is reconstructed according to the male poet's point of view, resulting in the recreation of an idealized woman who thus becomes his possession.

It is the poem that gives the man the woman of his dreams. And should it be otherwise? Shouldn’t the man possess the woman he has invented for his poem? Ethical aesthetics aside, one sees the blazon move into English through the influence of Petrarch, whose sonnet form thrived during the Elizabethan literary period. Edmund Spenser, for example, uses blason in his poem, “Epithalamion,” where

Her goodly eyes like sapphires shining bright,

Her forehead ivory white …

The simile compares his subject’s eyes to shiny jewels; the describes her perfect forehead, etc. Spenser also used this technique in “Sonnet 64” from Amoretti, comparing each feature of the beloved woman to a flower. A whole garden in a woman’s body! A stunning tablecloth!

Sir Philip Sidney’s “Sonnet 91”, a Petrarchan sonnet from Astrophil and Stella, parodies the blazon by questioning singularity. Here, we find the speaker, Astrophil, missing his love, Stella, and warning her not be jealous if he sees or interacts with other beautiful women, since all he can see when he looks at them is her:

They please, I do confess; they please mine eyes,

But why? Because of you they models be,

Models such be wood globes of glist’ring skies.