The challenge is always to find the ultimate in the ordinary horseshit.

— James Tate, “South Bend”

People read poems like newspapers, look at paintings as though they were excavations in the City Center, listen to music as if it were rush hour condensed. They don't even know who's invaded whom, what's going to be built there (when, if ever). They get home. That's all that matters to them. They get home. They get home alive.

— James Tate, “Read the Great Poets”

Harold Feinstein, Piano Still Life, 1974.

Vintage gelatin silver print; photo taken by Anne MacDougall.

The titular framing fueled the fire. An unexpected kindling got starred by a spark. I remember being drawn to “The Whole World’s Sadly Talking To Itself”, a poem by James Tate titled (perhaps) after phrasing from a poem by W. B. Yeats. Or by an ekphrastic urge, I’d read poems by Tate prior to this one and felt missed by them; none left a mark until I entered the building Tate assembled beneath Yeats’ awning—

What about this poem reached out to me? Which part of my existence felt apprehended in (or by) its being?

An elegance in the stanzaic construction. An intertextual friskiness in the speaker’s engagement of motifs and phrases hatched while marveling over the work of another. An alluring ghost-presence of images from Yeats’ poem, “The Sorrow of Love”, with its repeated conjunctions:

And then you came with those red mournful lips,

And with you came the whole of the world’s tears

And all the trouble of her labouring ships,

And all the trouble of her myriad years.

Or maybe a gist of Yeats’ “Broken Dreams” — though it seems too dedicated, too intent on cherishing what has aged rather than what was empty.

I can’t remember.

The way I imagine it has nothing to do with its reality, or with Tate’s realization. And I like that in a poem. I value being being strung out on a line, trying to locate my affective response on a range between disappointment and fascination. Two friends chew over edits in their overly-meaningful poems. They go out for drinks and leave each other with words. Riddling words that want definition. Poems excel at riddling the definitive parts of language, and — in my imagination — Tate writes “Two for Charles Simic” in dialogue with the possibility of defining the sky or nothing.

But here’s how it actually happened:

Two for Charles Simic

1. The Sky

What is the sky?

A week later

I reply: I don't know

why don't you ask

your only friend.

Another week passes.

He doesn't call.

He must be up to something,

he must know

what the hell it is.

I look at my bankbook,

it's forty-seven below.

Can you give me a clue?

I blurt at him.

Those few shining masterpieces

are lost, electric piercing

bouquets

lost in a fantastic fire.

What is the sky?

What is the sky.

The sky is a door,

a very small door

that opens for an inchworm

an inch above his rock,

and keeps his heart from flying off.

2. Nothing

It is a tiny obscure lighthouse

for serious travellers of the night

whose only vocation

is to gradually discover a spot

to root their lonely wardrobes.

It is a dignified fifth columnist

inspiring unheard of wind

slightly ajar:

if you haven't got any you'll die.

It's not going to improve your posture.

Take an overdose and you won't even faint.

It helps you make it through the day.

You can take it with you and that's all.

Notice the thing that happens between the sixth and seventh stanzas of the Sky section in the prior poem. . . I’m highlighting the repetition across the stanza break —

What is the sky?

What is the sky.

— because this punctuation of a questing statement with a period is precisely how Tate opens “Read the Great Poets.”

“What good is life without music.”

Maybe a species of rhetoric that resembles a musing.

The same being “The Masters. The Thieves.”

Another sameness sluiced from the repetition of phrases — like “They get home” at the close of the fourth stanza — that reinforces the claim at the end of the third stanza: “We are playing the same song and no one has ever heard anything.”

Speaking of actual happenings, Simic interviewed Tate for The Paris Review in 2006. This is where I learned that Tate was four months old when his father’s plane was shot down in Europe, a tragedy that his mother steadfastly refused to believe. Serving his eggs deadpan, Tate plays on the surreality of circumstance:

This is pretty unfair to the very nice man she was married to for the last thirty-four years of her life—but she was always in love with my father. It was a high-school love affair, they married young, and she never got over it. She came to visit me in Spain in 1976 and she was really crazy. She had never been abroad and it just rattled her to the core. Shortly after she got off the plane she said, I’m really hoping I’ll meet your father.

In the same interview, Tate said he loved taking a poem “that starts with something seemingly frivolous or inconsequential and then grows in gravity until by the end it’s something very serious.” And this is visible across his work. You can see it “Very Late, But Not Too Late,” and how it opens on that see-saw of Tate-style scandal:

I was the last one to leave the party. I

said goodnight to Stephanie and Jared. They were

already in bed. In fact, they were making love, but

they stopped and thanked me for coming.

You can also glean it from the first lines of the cheeky portrait titled “The Chaste Stranger”:

All the sexually active people in Westport

look so clean and certain, I wonder

if they’re dead. Their lives are tennis

without end, the avocado-green Mercedes

Frequently, Tate’s titles work against the loom of their promise. Humans who rarely laugh at disappointment may find Tate too glib. But I kept reading him over the years, bonding with his affinity for absurdity, the drift of that “cuppa” pitched in the invitation elaborated at the outset of “You Are My Destination and My Desire, Fading” —

Something wistful in the slope of “our initials rising” after the strenuous obit-reading mingled with the “fissures” and the fossil record. Something suggestive of absence.

Something displaced in the chaos beneath the foggy day that unfurls with “my cockatoo” and continues with the “some poky guy” amid the flourish of alliteration that sounds out the poem Tate tited “Editor.”

Something bluer than midnight in the disorder of “the plump and dusky woman with something on a leash” setting the scene for the absurdity of luck and pennies offered to “The Condemned Man.”

Something resembling a response to the horrible luck of his childhood’s inheritance.

Something Tate said to Simic evokes it:

My mother got married. It was a brief and very unfortunate marriage to a dangerous lunatic who shot holes in our house with a .45 automatic. He slit his wrists—all kinds of stuff. It was only years later, when I happened upon the one and only photograph that I had of him, that I realized that he bore a considerable resemblance to my father. She had married him from the gut—like, oh, he’s like Vincent. And he was. He was a nice-looking man, with the same exact curly hair and very similar features. It was that simple. She married him after knowing him two weeks. I hadn’t even met the guy. She came home and said, We’re moving out of here. I’m married!

The marriage may have been a disaster but Marriage, as an institution, survived its dissolution: Tate’s mother remarried a traveling salesman who sold shock absorbers. Tate’s second stepfather was a man with “a who-knows-how-many-state area, maybe five states” who “was gone pretty much all week, thank God.” In Tate’s words:

I really don’t remember him doing anything to me, but he used to beat the shit out of my mother. Really badly—black-and-blue—and I would be in the house watching. Eventually, toward the end of it, I drew a gun and stuck it to his head. His own gun. He had told me where he hid it. To protect the house, you know? He told me where it was, and I finally went and got it. It really was time to do it. I was probably sixteen.

He left his job as a dishwasher in New York city after being held up at gunpoint. But he knew its nocturnes well enough to compose them “In New York,” where:

you sometimes know the secret, if anything,

not asking for anyone to take you home

you are, for one second, the only one that's not alone and

There is something worth returning for in “the blue-black plumes of the foundation” of “City At Night”.

There is more: the aunt “stroking the back of a standing raccoon” in “Demigoddess”; “this crap about a cougar” in “Half-Eaten”; “Millie, O Millie, do you remember me?” . . .

“Dear Gene, I made it at least this far,” Tate wrote in a 1969 letter addressed to his friend Gene DeGruson — followed by a juicy inventory of details from the “writhing” life:

The infinite details involved in moving from one place to no-place wrought a maniacal kind of SS effiency upon me those last 2 weeks. I sold my car and much of my “furniture,” as it was. And I do have three readings in Pennsylvania before departing the continent; plus one charity reading at Yale.

It’s good to be away from Kansas City: as you know, I had no real stimulating friends there, just a few drinking partners and a nice girl, which is enough to get by on for a while, but not nine months, for me. I attended a wild party and poetry event last night at Saint Mark’s Church on the Bowery—LSD punch (really!) pot birthday cake, plus 350 joints circulating for the special occasion, plus wine, a small conciliation. I abstained from the punch, but indulged in the cake and joints. The wildest thing was this: good old Ingrid Superstar herself picked me as her evenings entertainmnet, Warhol’s debutante. Cosmic mindlessness! I was absolutely giddy with the whole thing, couldn’t stop beaming at the ridiculousness of it. Since she was the big catch at the event, everyone had their eyes on us to see what would come of it (I think she had vaguely heard of me, though I couldn’t tell for sure, and I made no effort to inform of my literary inclinations because nothing could have been more irrelevant to her designs.) Well, I blew it. It was too much, I walked her to her apartment, listening to her gobbledegook about the eclipse in China that night and how she was a scorpio, and how many pills she had taken that day and her last bad trip and her next movie in Rome, etc etc., and finally stole a big kiss goodnight and slithered back down 10th to the Church where the party was still writhing. All the East Village poets were there—Ron Padgett, Michael Brownstein, Peter Schjeldahl, Anne Waldman, Gerard Malanga, Lewis Warsh, and more, plus a few friends of mine, Charles Simic and Nathan Whiting, both of the latter being very good poets—the former six being extremely suspect though much celebrated in this part of the world, thanks to their dial-a-poem innovation.

There are as always many plays and movies and poetry events buzzing here: and you keep thinking you’ll take them all in but when the clock says it’s time to go you sink deeper in your chair at the thought of three subway transfers and you end up reading a book and drinking a bottle of wine. I don’t know where I’ll live when it’s Columbia teaching time next year.

The City is in a mess in so many ways. Lindsey is in fact a baboon. Norman Mailer is going to be running with Jimmy Breslin as city counsel chairman. He might even win. The schools are hopeless, much money has been cut for all budgets, there is no housing, rents are skyrocketing, etcetera. Aguh. Oh for the prairies. You can’t win.

Let me know what you’re up to, now and in the summer ahead.

“Adieu, Yours, Jim.”

Some He might win but You definitely can’t. Not in a Tate poem. Not in a Tate-world. If you’re patient and willing to watch, you can bard over the terrors in silly-string. Imagine them otherwise. Refuse to be bound by their steam.

In Memory, Dorothea Lasky describes how fear and art linked up for her as a child. “I used to draw a picture of the scariest thing I could think of on a piece of paper and then cover it up,” she writes. “Then I'd test myself to see if I was brave enough to look at it. I'd cover and uncover the page quickly, letting the image wash over me, without really forcing myself to look directly at its hellish stare. Even now I feel scared of finding one of those pages somewhere (or it finding me).”

On that note, “Coda” deserves to be read them. Tate’s descriptive restraint reinforces his refusal to take up horizontal space on the page, pulling the poem down as if compelled by gravity. Here it goes.

Coda

Love is not worth so much;

I regret everything.

Now, on our backs,

in Fayetteville, Arkansas,

the stars are falling

into our cracked eyes.

With my good arm,

I reach for the sky

and let the air out of the moon.

It goes whizzing off

to shrivel and sink

in the ocean.

You cannot weep;

I cannot do anything

that once held an ounce

of meaning for us.

I cover you

with pine needles.

When morning comes,

I will build a cathedral

around our bodies.

And the crickets,

who sing with their knees,

will come there

in the night to be sad

when they can sing no more.

*

Charles Simic, “James Tate, The Art of Poetry No. 92” (Paris Review)

Ferruccio Busoni, Piano Concerto (1878)

Harold Feinstein, Piano Still Life, 1974.

James Tate, “Editor”

James Tate, “Fuck the Astronauts”

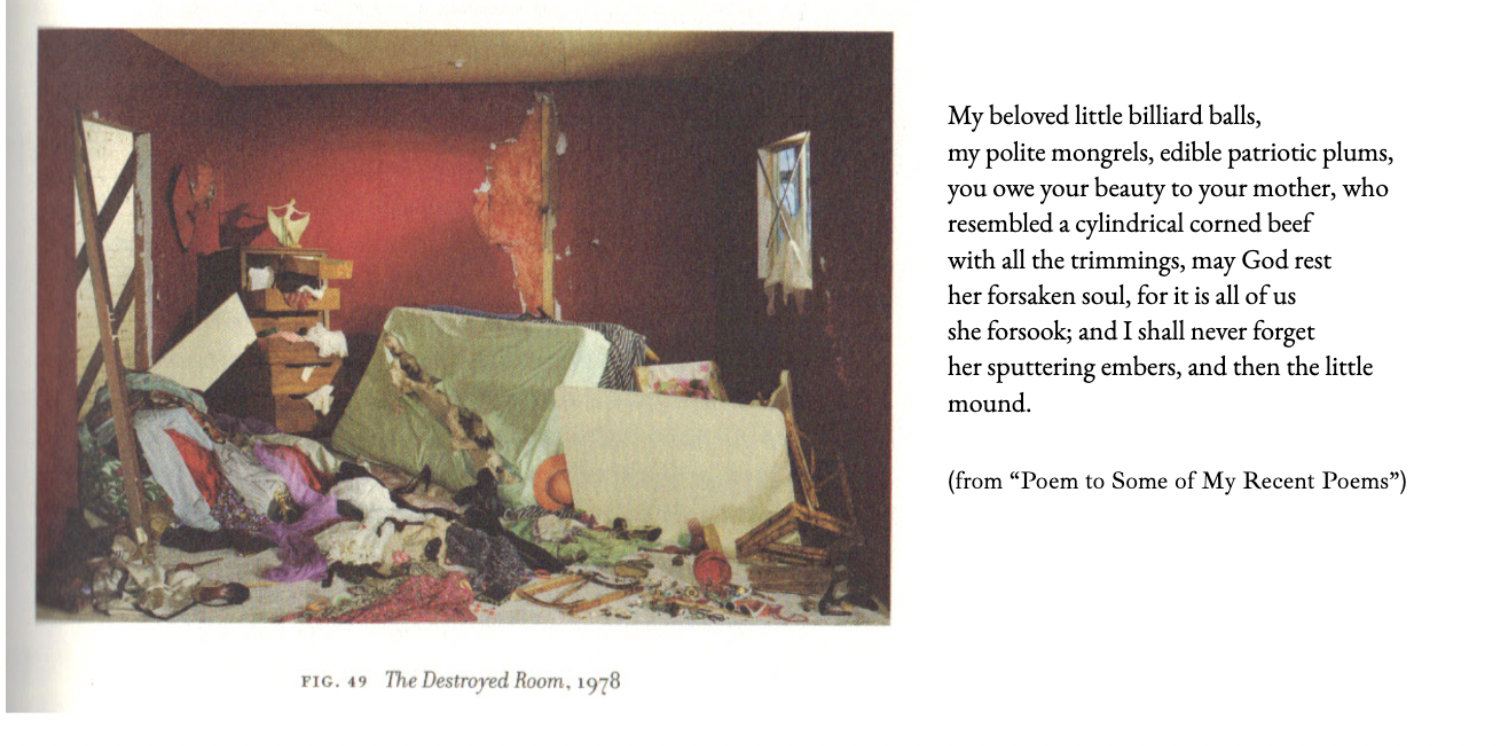

James Tate, “Poem to Some of My Recent Poems”

James Tate, “The Condemned Man”

James Tate, “The Expert” (PDF)

Jeffrey Gleaves, “Cosmic Mindlessness” (Paris Review)

W. B. Yeats, “Broken Dreams” (PDF)