The marvelous Barbara Johnson led me back to Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Marble Faun, and the challenges posed by ruins to representation, particularly in the Protestant disparagement of images and iconography. Hawthorne wrote the novel directly from the notebooks kept while serving a diplomatic post in Italy, accompanied by his wife, a sculptor.

In the scene that held my attention last night, the sculptor named Kenyon asks his friend, Hilda (the painter who specializes in copying details from the works of Old Masters) for her thoughts on his attempt to sculpt Cleopatra. Hilda responds to Kenyon’s expressive, complicated, and moody Cleopatra with admiration, for it is indeed is spectacular; the statue openly inhabits classicism while pushing the affective range closer to the intensity of the Vatican’s Laocoön (which Kenyon coveted). And it is Kenyon’s response to Hilda’s complimentary tone that interests me.

“Ah; your kind word makes me very happy,” he says to Hilda, “and I need it, just now, on behalf of my Cleopatra. That inevitable period has come, (for I have found it inevitable, in regard to all my works,) when I look at what I fancied to be a statue, lacking only breath to make it live, and find it a mere lump of senseless stone, into which I have not really succeeded in moulding the spiritual part of my idea. I should like, now —only it would be such shameful treatment for a discrowned queen, and my own offspring, too—I should like to hit poor Cleopatra a bitter blow on her Egyptian nose, with this mallet!”

Hilda laughs and tells Kenyon, “That is a blow which all statues seem doomed to receive, sooner or later, though seldom from the hand that sculptured them.” Then she attempts to address the underlying issue, namely, Kenyon’s feeling that he has failed to create the object he imagined. “You must not let yourself be too much disheartened by the decay of your faith in what you produce,” Hilda says. She continues:

I have heard a poet express similar distaste for his own most exquisite poems; and I am afraid that this final despair, and sense of short-coming, must always be the reward and punishment of those who try to grapple with a great or beautiful idea. It only proves that you have been able to imagine things too rich for mortal faculties to execute. been able to imagine things too high for mortar faculties to execute. The Idea leaves you an imperfect image of itself, which you at first mistake for the ethereal reality, but soon find that the latter has escaped out of your closest embrace.

To which Kenyon replies, “And the only consolation is that the blurred and imperfect image may still make a very respectable appearance in the eyes of those who have not seen the original.”

Can the imperfect be a consolation? Well, it depends on the character. Hilda’s moralism and desire for purity confounds the notion of “goodness” in The Marble Faun, with the irony being that her dedication to copying the works of Old Masters positions itself as a repetition or recollection of perfection and purity. How is this recollection more innocent than daring to imagine and invent one’s own way of being or seeing?

Where Kenyon grants the “consolation” of achieving his art achieving a “respectable appearance” in the eyes of those who can’t compare Kenyon’s statue to the “original” in his mind, Hilda pushes past this and insists that:

“. . . there is a class of spectators whose sympathy will help them to see the Perfect, through a mist of imperfection. Nobody, I think, ought to read poetry, or look at pictures or statues, who cannot find a great deal more in them than the poet or artist has actually expressed. Their highest merit is suggestiveness.”

“You, Hilda, are yourself the only critic in whom I have much faith,” said Kenyon. “Had you condemned Cleopatra, nothing should have saved her.”

“You invest me with such an awful responsibility,” she replied, “that I shall not dare to say a single word about your other works.”

For Hilda, this merited “suggestiveness” can only be pedagogical, or instructive in living the virtuous life. In many ways, she represents the belief that what we consume determines the moral value of what we create, think, imagine, and live. By reproducing the works of Old Masters, she risks nothing. She overpopulates her imagination with the conventional standards of beauty and goodness, only to find herself incapable of recognizing morality that looks different. For the Hildas of the world, the moral realm is accessed through beauty, through a sort of aestheticism that disclaims personal preference in the name of the Greater Good, the Formal Perfection, the Beautiful. It is lonely in Hilda’s tower, since anything foreign or strange poses a threat to its simple rubric. How can we feel alongside a world in which having pink heresy would be heretical? How do our boxes and categories that specialize in recognition (or make recognition authoritative) limit the possibilities of the prefigurative?

In the sidereal, an excerpt from Herman Melville’s letter to Hawthorne in June 1851:

“The ancient poets thought of the publication of a poem as the time of saying it, and the time of saying it is also the time of it being heard, and that's the time when there's an exchange of that action, that verb, whatever the verb is that's being described,” Anne Carson said to Kevin McNeilly in an interview, adding— “The verb happens.” Unfinish it.

*

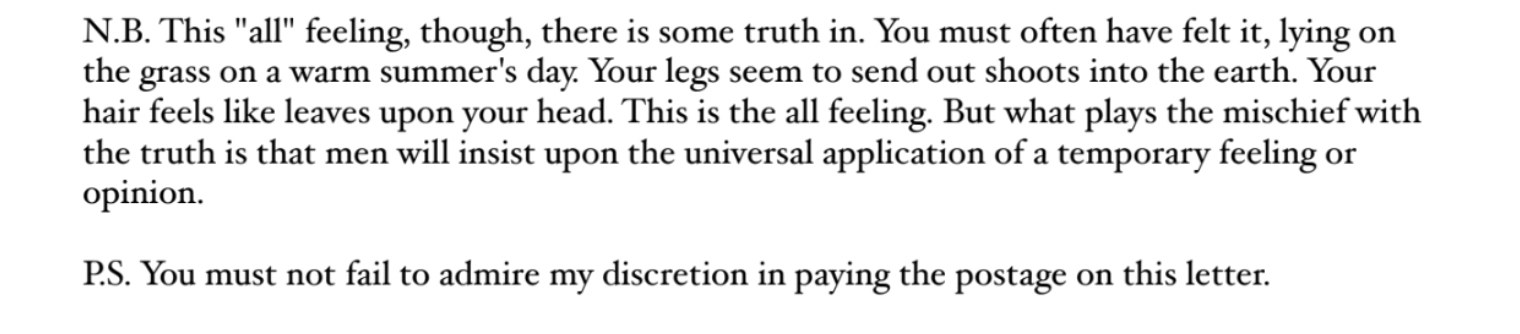

Anna Bilińska-Bohdanowicz, Portrait of Sculptor George Grey Barnard in his Atelier (1890)

Crooked Fingers, Cover of Prince’s “When U Were Mine”

Herman Melville, “Letter to Nathaniel Hawthorne, June 1851”

Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Marble Faun

William Orpen, Woman Dressing (sketch)