You name a city and you’ve already been there.

— Elias Canetti’s “fun-runner”

My grandfather in me cannot decide. So that's where I got the indecisiveness that will constantly torment me.

— Georgi Gospodinov

1

When I finished reading Georgi Gospodinov's novel, The Physics of Sorrow, translated by Angela Rodel, I was sitting on a bench near the Piggly Wiggly. The world of the book had ended, replaced by a random procession of humans entering and exiting the store, carrying plastic bags or brown paper bags or multi-colored reusable bags. I thought about lists, and how each person had come with a list of things they needed; each one had “something” in mind when they arrived at the store.

On the walk home, carrying Gospodinov in my head for the duration of five city blocks, I considered the importance of lists in his novel.

2

List, as a noun, refers to “a number of connected items or names written or printed consecutively, typically one below the other.”

To list, as a verb, is to create the noun form of this word, list.

Synonyms for “list” include catalog, inventory, record, register, roll, file, index, directory, listing, listicle, checklist, tally, docket, ticket, enumeration.

In an anthology of Roland Barthes' writing edited by Susan Sontag, one finds two lists by Barthes, two inventories of likes and dislikes:

I like: salad, cinnamon, cheese, pimento, marzipan, the smell of new-cut hay (why doesn’t someone with a “nose” make such a perfume), roses, peonies, lavender, champagne, loosely held political convictions, Glenn Gould, too-cold beer, flat pillows, toast, Havana cigars, Handel, slow walks, pears, white peaches, cherries, colors, watches, all kinds of writing pens, desserts, unrefined salt, realistic novels, the piano, coffee, Pollock, Twombly, all romantic music, Sartre, Brecht, Verne, Fourier, Eisenstein, trains, Médoc wine, having change, Bouvard and Pécuchet, walking in sandals on the lanes of southwest France, the bend of the Adour seen from Doctor L.’s house, the Marx Brothers, the mountains at seven in the morning leaving Salamanca, etc.

And what does Barthes dislike?

I don’t like: white Pomeranians, women in slacks, geraniums, strawberries, the harpsichord, Miró, tautologies, animated cartoons, Arthur Rubinstein, villas, the afternoon, Satie, Bartók, Vivaldi, telephoning, children’s choruses, Chopin’s concertos, Burgundian branles and Renaissance dances, the organ, Marc-Antoine Charpentier, his trumpets and kettledrums, the politico-sexual, scenes, initiatives, fidelity, spontaneity, evenings with people I don’t know, etc.

The list form underscores an implicit connection between the things that come to mind (or the things we think about) and noticeability, or the act of discovering our preferences. We notice what we like and what we dislike. Oddly, making a list of our preferences assumes that the unnoticed exists, and the unnoticed remains in the margins with the unremarkable. The noticed, and the noticeable, speaks to the biases inherent in the act of seeing; it also calls the discourses of visibility into play.

3

Barthes’ lists use the construction “don't like” rather than “dislike.” This may be a question of translation that allows to consider the difference between claims of not liking vis a vis claims of actively disliking.

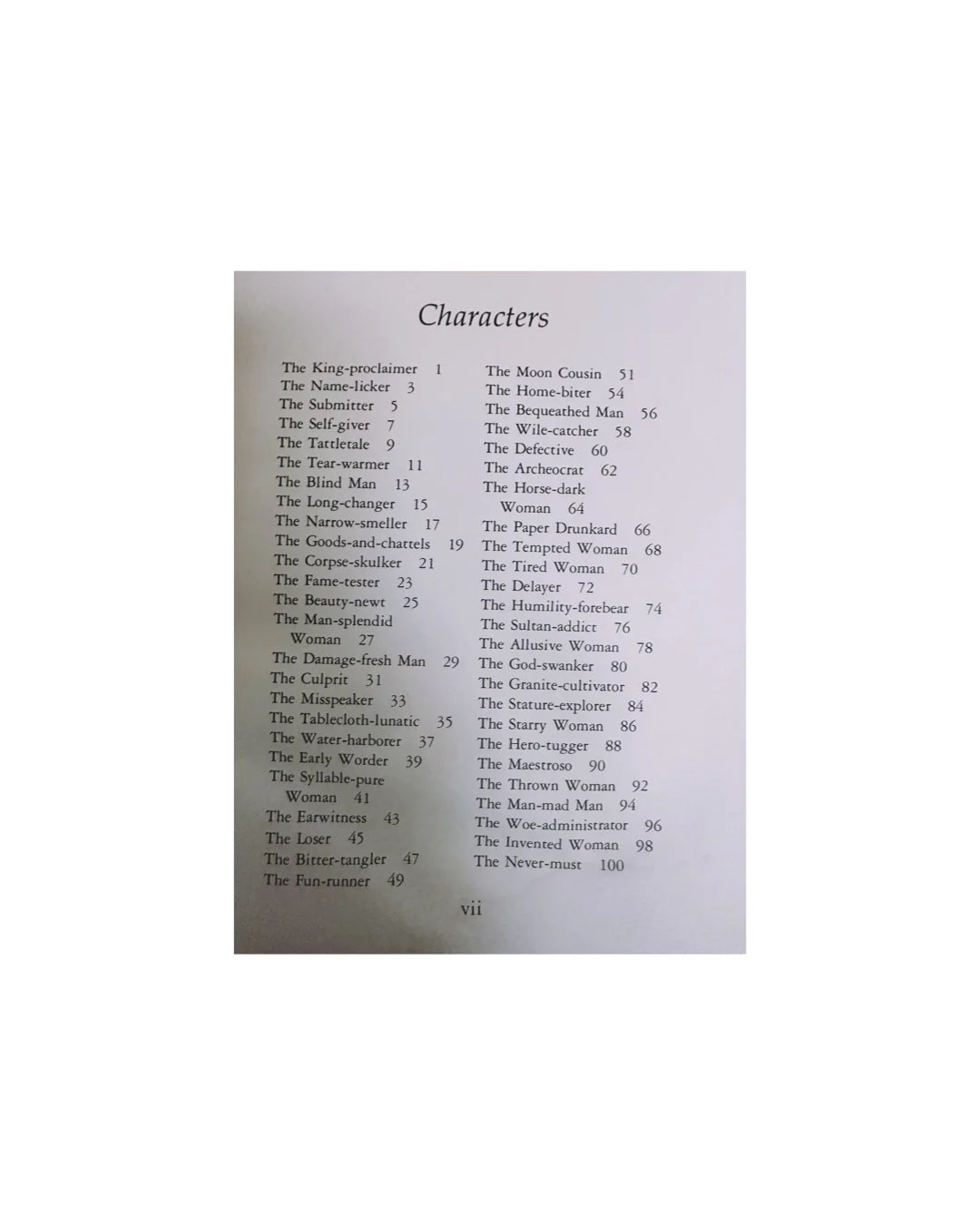

Speaking of lists, the table of contents for Elias Canetti’s Earwitness: Fifty Characters reads like a list . . .

Blending literary criticism, social psychology and parabolic swagger, Canetti’s fifty short portraits borrow their style from the Greek philosopher Theophrastus as well as that of seventeenth century English essayists. Word play, of course, doubles as punctuation; sarcasm dances through stereotypes; irony reigns in Canetti’s fabulist satirization of psychological and sociological categories. “The Corpse Skulker” delights in death; “The Fun Runner” consumes pleasure on a scoreboard with no capacity to savor; “The Defective” remains sure of themselves thanks to an inferiority complex. Some have wondered how much the writer, which is to say, the author himself, might have been implicated in the Canetti’s portrait of “The Earwitness” (which I share in its totality below):

The Earwitness

The earwitness makes no effort to look, but he hears all the better. He comes, halts, huddles unnoticed in a corner, peers into a book or a display, hears whatever is to be heard, and moves away untouched and absent. One would think he was not there for he is such an expert at vanishing. He is already somewhere else, he is already listening again, he knows all the places where there is something to be heard, stows it nicely away, and forgets nothing.

He forgets nothing, one has to watch the earwitness when it is time for him to come out with everything. At such a time, he is another man, he is twice as large and four inches taller. How does he do it, does he have special high shoes for blurting things out? Could he possibly pad himself with pillows to make his words seem heavier and weightier? He does nothing else, he says it very precisely, some people wish they had held their tongues. All those modern gadgets are superfluous: his ear is better and more faithful than any gadget, nothing is erased, nothing is blocked, no matter how bad it is, lies, curses, four-letter words, all kinds of indecencies, invectives from remote and little-known languages, he accurately registers even things he does not understand and delivers them unaltered if people wish him to do so.

The earwitness cannot be corrupted by anybody. When it comes to this useful gift, which he alone has, he would take no heed of wife, child, or brother. Whatever he has heard, he has heard, and even the Good Lord is helpless to change it. But he also has human sides, and just as others have their holidays, on which they rest from work, he sometimes, albeit seldom, claps blinders on his ears and refrains from storing up the hearable things. This happens quite simply, he makes himself no-ticeable, he looks people in the eye, the things they say in these circumstances are quite unimportant and do not suffice to spell their doom. When he has taken off his secret ears, he is a friendly person, everyone trusts him, everyone likes to have a drink with him, harmless phrases are exchanged. At such times, people have no inkling that they are speaking with the executioner himself. It is not to be believed how innocent people are when no one is eavesdropping.

- Elias Canetti (t. by Joachim Neugroschel)

4

As a form, the LIST gestures towards infinitude — for how can a list be considered complete? Even granting the list's location in time and space, one cannot help thinking that the list might look different if the list-maker had spent a few more minutes wandering through his own mind. This tension between the list's efficiency, or its capacity to draw forth and enumerate, and its false relation to finitude makes it a wonderful thought device.

“The list could surely go on, and there is nothing more wonderful than a list, instrument of wondrous hypotyposis,” Umberto Eco wrote. In an essay subtitled “the poetry of the archive,” David Levi Strauss noted how Eco's "wondrous hypotyposis . . . points to the work of lists as sketches, outlines, or patterns.” Tracing the word’s etymology, he adds: “The Greek hupotuposis derives from tipos, ‘an impression, form, or type.’ When lists become compendious, they list toward the rhetorical figure of hypotyposis, ‘by which a matter [is] vividly sketched in words.’”

The “list-lust” may be central to the craft, as Strauss writes in this eminently-quotable passage:

Strauss credits this engagement with Golub's lists as speculating forth “a new form of imagism—list imagism, or, as Leon might have it, 'jittery image-jism'.” The sonics of Strauss’ neologism, “jittery image-jism,” plays into the motion and tenuousness of the list form.

[Aside to self: represent the materials of a textual list non-textually in order to reveal their plasticity.]

Excerpt from one of Leon Golub’s lists, as quoted by David Levi Strauss.

5

Like Elias Canetti, Georgi Gospodinov was born in Bulgaria.

Unlike Canetti (who wrote in German), Gospidinov writes in Bulgarian.

I mention this because Canetti was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1981, an event that some critics have interpreted as a win for the Bulgarians, an interpretation which strikes me as strange and yet perhaps much more common for winners that hail from Eastern or Central Europe. When Herta Müller won the Nobel Prize in 2009, it was a win for the German language more than a win for Romania or a nation-state. Given the entanglement of translation, publishers, profit, power, with the distance between major languages and minor languages, it might make more sense to qualify the Nobel with a mention of the writer’s language rather than their ‘nationality’. After all, nation-states die or are born continuously. There is no end to the parsing and confusion of awards attached to countries that no exist.

(As I have said elsewhere, it is my hope that Gospodinov receives international recognition for his extraordinary books. It is my humble opinion that the Nobel Committee might consider awarding a prize to literature written in the Bulgarian language.)

Coincidentally, in a friskier tenor, Susan Sontag regaled Canetti’s work in review essay published in the New York Review of Books in the year just prior to Canetti’s Nobel 1981 win. She praised Canetti’s particular sense of the grotesque and drew a connection between his early projected work and the monomania of Earwitness:

More on Gospodinov soon . . .

In the interim, I leave you with a little wit, a little exclamatory, and a little blasphemy as written by Canetti in one his portraits:

“The damage-fresh man has a wry face and a nasal twang. He cares little for people and seeks proof. He knows people only if something goes awry for them.”

— Elias Canetti

*

Carolyn Birsdall. “Earwitnessing: Sound Memories of the Nazi Period.” Sound Souvenirs: Audio Technologies, Memory and Cultural Practices, edited by Karin Bijsterveld and José van Dijck, Amsterdam University Press, 2009, pp. 169–81.

David Levi Strauss. “Inventory/ Fallen Figures & Heads: Leon Golub's Lists.” Cabinet Magazine, Issue 13, Spring 2004.

Elias Canetti. Earwitness: Fifty Characters. translated by Joachim Neugroschel. New York: The Seaburry Press, 1979.

Frank Tonkiss, “Aural Postcards: Sound, Memory, and the City.” The Auditory Culture Reader, edited by Michael Bull and Les Black, Berg Press Sensory Formation Series, pp. 303-309.

Georgi Gospodinov. The Physics of Sorrow, translated by Angela Rodel.

Susan Sontag, “The Mind as Passion: On Elias Canetti” (New York Review of Books, September 25th, 1980)

Steve Reich, “I. Strings (With Winds and Brass)” fromThe Four Sections, performed by London Symphony Orchestra.

My tattered old copy mit a sunflower face discovered on a nightwalk this week.