Scriabin’s “Prefatory Action” from the Mysterium

Artist Jean Delville’s title page for Scriabin’s Promethée, originally a section of the Mysterium.

I read Faubion Bowers’ biography of Alexander Scriabin this October—and the fascination with eschatology and apocalypse in late 19th century Russia doesn’t feel foreign to the present moment.

In 1903, Scriabin started working on Mysterium, an eschatological, world-ending symphony that would engage all the senses. He wanted it to be performed in the Himayalan foothills of India, and take place over the course of a week culminating in the end of the world and the replacement of the human race with "nobler beings". In Scriabin’s words, the whole world would be invited, including animanls, insects, and birds:

There will not be a single spectator. All will be participants. The work requires special people, special artists and a completely new culture. The cast of performers includes an orchestra, a large mixed choir, an instrument with visual effects, dancers, a procession, incense, and rhythmic textural articulation. The cathedral in which it will take place will not be of one single type of stone but will continually change with the atmosphere and motion of the Mysterium. This will be done with the aid of mists and lights, which will modify the architectural contours.

Artists of all kinds would contribute to the seven-day ritual; the audience’s senses would be dazzled by lights, incenses, textures, music and poetry. Alongside Theosophist Emile Sigogne, Scriabin “worked on an absolutely new language for the Mysterium. It had Sanskritic roots, but included cries, interjections, exclamations, and the sounds of breath inhaled and exhaled.”

Bowers describes Scriabin’s “The Mysterium” and its prelude, the “Prefactory Action,” as “cataclysmic opuses to end the world and its present race of men.” In Bowers’ words:

The Prefatory Action would [...] be a stage work of immense proportion and conception. Bells suspended from the clouds in the sky would summon the spectators from all over the world. The performance was to take place in a half-temple to be built in India. A reflecting pool of water would complete the divinity of the half-circle stage. Spectators would sit in tiers across the water. Those in the balconies would be the least spiritually advanced. The seating was strictly graded, ranking radially from the center of the stage, where Scriabin would sit at the piano, surrounded by hosts of instruments, singers, dancers. The entire group was to be permeated continually with movement, and costumed speakers reciting the text in processions and parades would form parts of the action. The choreography would include glances, looks, eye motions, touches of the hands, odors of both pleasant perfumes and acrid smokes, frankincense and myrrh. Pillars of incense would form part of the scenery. Lights, fires, and constantly changing lighting effects would pervade the cast and audience, each to number in the thousands. This prefaces the final Mysterium and prepares people for their ultimate dissolution in ecstasy.

Supposedly, if everything proceeded according to plan, the first and only performance would immanentize the eschaton, thereby annihilating space and melting reality. No one would even have to pay the performers.

Scriabin’s drawing of part of the Mysterium set

At the time of his death in 1915 from sepsis (which came as a result of an infected sore on his lip), Scriabin had sketched 72 pages of a prelude to the Mysterium, entitled Prefatory Action. Because Scriabin died young, he left the piece intended to bring about the end of the world—or to bring together all the cosmos in a sort of cataclysmic unity—unfinished.

2. Alexander Nemtin’s “Prefatory Action”

Russian composer Alexander Nemtin decided to finish Scriabin’s “Prefatory Action.” He started in 1970 and delivered the final piece in 1996, three years before dying. Here is how Colin Clarke describes the recording of Nemtin’s realized “Preparatory Action”:

Alexander Nemtin's brave realization of the "Preparation for the final mystery" (from Scriabin's magnum opus, Mysterium) enables us to hear its awe-inspiring conception in all its glory. Working from sketches, Nemtin presents a convincing manifestation of Scriabin's thought. The intensity of this piece is unremitting. To listen straight through is an exhausting but ultimately uplifting experience, one aided by this thoroughly committed performance from Ashkenazy and his Berlin forces. Even though the harmonic language is extremely concentrated, the progress of the work remains involving, natural, and, above all, gripping. The music is frequently hypnotic, often breathing an all-encompassing, pantheistic mysticism. The soloists, particularly the soprano Anna-Kristina Kaappola and the pianist Alexei Lubimov, are superb. The recording aptly conveys the requisite sense of space, while simultaneously allowing every detail to come through. The coupling, Nuances, comprises a selection of Scriabin's pieces orchestrated to form a ballet. Ashkenazy's performance highlights the elusive nature of this music, as in the flighty fourth movement or in the twilight world of the 12th.

You can listen to it here. And here is performance that includes the full score.

3. Johanne Sebastian Bach’s so-called “Neverending Canon”

Composed later in his life, this Bach masterpiece has a single subject surrounded by dozens of contrapuntals—and it includes this endlessly ascending canon. It's an unstructured, unorchestrated collection of manuscripts with enough puzzles and enigmas to make Elgar proud. The Neverending Canon (or Perpetual Canon) was part of Bach’s The Musical Offering, a 1747 collection of keyboard canons and fugues based on a single musical theme given to Bach by King Frederick II of Prussia—and they are dedicated to this patron. Among the pieces:

The Ricercar a 6, a six-voice fugue which is regarded as the high point of the entire work, was put forward by the musicologist Charles Rosen as the most significant piano composition in history (partly because it is one of the first).This ricercar is also occasionally called the Prussian Fugue, a name used by Bach himself. The composition is featured in the opening section of Douglas Hofstadter's Gödel, Escher, Bach.

Other notes from wikipedia on Bach’s The Musical Offering:

Some of the canons…are represented in the original score by no more than a short monodic melody of a few measures, with a more or less enigmatic inscription in Latin above the melody. These compositions are called the riddle fugues (or sometimes, more appropriately, the riddle canons). The performer(s) is/are supposed to interpret the music as a multi-part piece (a piece with several intertwining melodies), while solving the "riddle". Some of these riddles have been explained to have more than one possible "solution", although nowadays most printed editions of the score give a single, more or less "standard" solution of the riddle, so that interpreters can just play, without having to worry about the Latin, or the riddle.

One of these riddle canons, "in augmentationem" (i.e. augmentation, the length of the notes gets longer), is inscribed "Notulis crescentibus crescat Fortuna Regis" (may the fortunes of the king increase like the length of the notes), while a modulating canon which ends a tone higher than it starts is inscribed "Ascendenteque Modulatione ascendat Gloria Regis" (as the modulation rises, so may the king's glory).

The canon per tonos (endlessly rising canon) pits a variant of the king's theme against a two-voice canon at the fifth. However, it modulates and finishes one whole tone higher than it started out at. It thus has no final cadence.

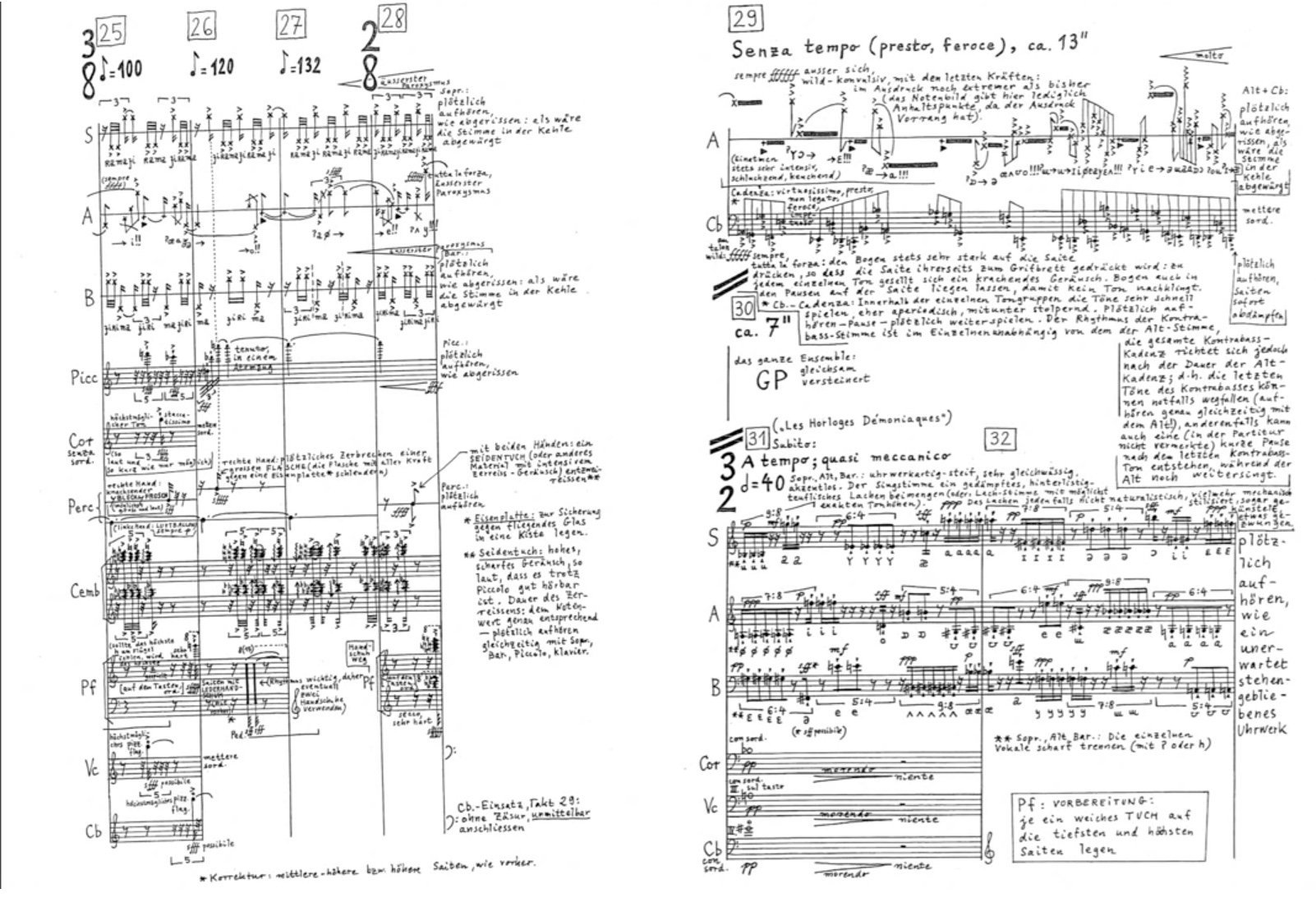

4. Karlheinz Stockhausen’s “Helikopter-Streichquartett”

Stockhausen composed a quartet of string players and four helicopters. The piece stands alone, but also exists as a scene from his epic opera, Mittwoch aus Licht. This epic musical cacophony was first performed (and even recorded) in 1995, to the delight of chamber music and aviators alike. Pictured above, Stockhausen’s score for the beginning of the first cycle—which I found at this incredible Stockhausen blog, alongside an extensive analysis of the piece itself.

I have watched this 2012 performance by the Elysian Quartet performing at least seven times today—the helicopters change the way perspective in this piece, or they do something marvelous with the assumed speaker.

5. Jim Fassett’s “Symphony of the Birds”

In the 1950s, Jim Fassett composed a symphony made entirely of recordings of birdsong. The result was “Symphony of the Birds,” an early electronic manipulation/ musique concrete masterpiece. Working with CBS radio technician Mortimer Goldberg, Fassett painstakingly pieced together fragments from recordings of bird calls originally made in the field by Jerry and Norma Stilwell.

What’s fascinating is that birdsongs weren’t always recorded—prior to recording technology, they were notated and symbolized by bird lovers who tried to capture them on paper using ohonetic transcription, or “bird words.” John Bevis’ essay on this history is worth reading.

From Sorajbji’s “Opus”

6. Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji’s “Opus Clavicembalisticum”

When completed in 1930, British Parsi composer Sorabji’s Opus was the longest piano piece in existence, lasting between 4 and 4.5 hours, depending on how tempo is intepreted. Pianists consider it to be a crushingly difficult contrapuntal piece. Sorabji may in part have been inspired to compose the work after hearing a performance by Egon Petri of Busoni's Fantasia contrappuntistica[1] and Opus clavicembalisticum is taken as homage to Busoni's work.

"The closing 4 pages are so cataclysmic and catastrophic as anything I've ever done—the harmony bites like nitric acid - the counterpoint grinds like the mills of God," Sorabji said. You can listen to various performances on the Sorabji website.

7. György Ligeti’s “Poème symphonique for 100 Metronomes”

How does rhythm influence a piece? What happens when the conventional tools for techne are allowed to speak or sing? During his dalliance with Fluxus, György Ligeti composed a work for ten performers, each responsible for 10 metronomes. The vision included 100 identical pyramid-shaped metronomes, fully wound up, each set to run at different speeds, to begin ticking simultaneously, gradually running down until only one is left to finally become silent.

“The audience should remain absolutely silent until the last metronome has stopped ticking,” Ligeti said. When it premiered in Holland in 1962, Poème Symphonique was so controversial at the time that in 1963 Dutch Television cancelled a broadcast of its performance, substituting a soccer game in its stead.

8. John Cage’s “Organ²/ASLSP (As SLow aS Possible)”

Organ²/ASLSP (As SLow aS Possible) consists of single notes or chords, which change very, very occasionally. The performance started in 2001, and it's continuing until the year 2640. In 2013 crowds flocked to St Burchardi church in Halberstadt, Germany to hear one of the notes change in performance. The history of the piece—like much of Cage—includes collaboration:

It was originally written in 1987 for organ and is adapted from the earlier work ASLSP 1985; a typical performance of the piano version lasts 20 to 70 minutes. Cage first wrote the piece, for piano, in 1985; the tempo instruction was, “As slow as possible.” He then reworked it for the organ in 1987, and it became known as “Organ²/ASLSP.” But that raised questions. On piano, the sound fades after a key is hit; on the organ, notes can be held indefinitely. Or can they? What about when the organist needs to eat, or go to the bathroom? Or dies?

Those questions occupied a group of composers, organists, musicologists and philosophers, some of whom had worked with Cage, at a conference in the town of Trossingen, in southern Germany, in 1998. They developed the idea of a performance calibrated to the life expectancy of an organ. The first modern keyboard organ is thought to have been built in Halberstadt in 1361, 639 years before the turn of the 21st century — so they decided the performance would last for 639 years.

In September 2020, the chord (pictured above) that was held since 2013 changed.

9. György Ligeti’s “Artikulation”

Ligeti wrote his electronic piece, “Artikulation,” in 1958. Although it existed as a recording, there was no score for musicians to 'see' the music. In the 1970’s, when studying this piece, Rainer Wehinger decided to “score” it—or to create this color-infused geometrical explanation of the music(pictured above), including a voluminous key explaining all the colours and symbols. In a sense, Wehinger made a map of the music, and maps may be another way of looking at a score.

10. John Cage’s “Aria”

Cage was a maestro of the graphic score, which sometimes feels close to a sort of visual or concrete poem in my mind. In “Aria” (pictured above), the graphic colored squiggles designate different styles of singing, notated in wavy lines in ten different colors, and the black squares indicate non specified 'non-musical' sounds.

11. Carl Bergstrøm-Nielsen’s “Towards An Unbearable Lightness”

Bergstrøm-Nielsen’s “Toward An Unbearable Lightness” (1992) was written “for any ensemble.” This beautiful graphic score can be played by any number of players, of any standard, on any instrument. All the performers follow the same instructions, and yet one ends up with so many interpretations—this short one or this longer one or even this arrangement of “grammar figures”.

The composer tells us: “The score is a graphic representation of a journey from heavy dark sounds to light sounds. Players progress at their own rate through the spiral representing this change, loosely coordinating with the other players.”

Like telling a child to draw a stairway to the stars, each visualizes the journey differently. By asking performers to do the work of creation-interpretation, Bergstrøm-Nielsen expands the varieties of available lightness. There is play, whimsy, and collaborative hope in this gesture.

12. George Crumb’s “Twelve Fantasy-Pieces after the Zodiac for Amplified Piano”

I return to George Crumb’s “Makrocosmos” often. With so many notes, this score would be difficult for any pianist to read if it was laid out simply on the page, which is why the score includes three detailed pages of instructions, with movements including Primeval Sounds, Crucifixus and Spiral Galaxy. David Burge’s recording of it has an interesting cover that inflects how one reads this—or maybe how I read it. Once the visual element of a poem or composition is engaged, it opens the door to visual tonal shading as well.

13. Tom Phillips’ “Ornamentik Op. IX”

Tom Phillips’ “Ornamentik” was composed for a trombone—and drawn at the request of an American player, Stuart Dempster, who wanted a piece that would provide various provocative challenges to corner him into inventing new sounds or techniques. According to the score:

ON THE PERFORMANCE: the piece may last any length of time. The piece consists of a held, sustained or otherwise maintained note, chord or sound, which is decorated (ascertainable time intervals) by brief ornamental flourishes derived from the symbols opposite, each ornament to be played once only. Where there is more than one player, the ornaments should be shared out more or less equally between the performers; any instruments or sound-sources may be used. As far as possible the ornaments should be read from left to right, with vertical alignment indicating simultaneity. Melody instruments or simple sources of sound may be augmented to cope with this. The ornaments may if necessary be adapted. The held sound is implied by the horizontal band which appears at either side of each ornament. Octave or timbre may change as well as dynamic, basically mp with a range between pp and mf: such changes can only take place at the end of an ornament. The piece should begin and end with the same timbre, octave etc.

More at Phillips’ website.

14. Stephen Antonsca’s “One Becomes Two”

Antonsca’s “One Becomes Two” was premiered by violinist Lina Bahn at the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC in March 2007—with Bahn’s violin plugged into Antosca's laptop and her violin generating ambient electronically-controlled responses that were repeated or transformed into “liquid reflections of her sound.”

The score is interesting because it lacks barlines and staves—the notation provides guidance to rhythm and pitch despite the absence of these conventional markers. And the piece itself is designated “for violin and real-time computer processing.”

On Antonsca’s website, near the piece, one finds a quotation from Carl Jung: “… when the bud unfolds and from the lesser the greater emerges, then One becomes Two and the greater figure, which one always was but which remained invisible, appears with the force of a revelation.”

15. Cilla McQueen’s “Picnic”

McQueen’s graphic scores are so close to art that one tastes the undertow of Kandinsky in the shapes and colors. In “Picnic,” written in 2006, each line represents a different instrument, with the colours and shapes informing how the music might sound. A small foray into this and others.

16. Cathy Berberian’s “Stripsody”

One of the most famous (and most cartoonish!) graphic scores is Cathy Berberian’s “Stripsody.” Written in 1966, it uses lines just like a traditional musical stave, indicating an approximate pitch for the singer. The difference being, the singer doesn't sing notes— she sings noises and words, with actions, including pretending to be a radio, roaring like Tarzan, and urging a kite to come down from a tree. The graphics are by Roberto Zamarin.

As a mezzo-sopran composer based in Italy, Berberian worked closely with many contemporary avant-garde music composers, including Luciano Berio, Bruno Maderna, John Cage, Henri Pousseur, Sylvano Bussotti, Darius Milhaud, Roman Haubenstock-Ramati, and Igor Stravinsky. Stripsody exploits her vocal technique using comic book sounds and onomatopoeia). In 1969, Berberian also brought us Morsicat(h)y, a composition for the keyboard (with the right hand only) based on Morse code.

17. Makato Nomura’s “Shogi Composition”

Carl Bergstroem-Nielsen has a wonderful short essay on Makato Nomura’s compositional methods. Here is how he describes the Shogi compositional method:

This is a principle of composition employed to several pieces since 1999. Shogi means "chess". Each player should have his own colour. Participants can create the score by their own ideas. When indicated in the score, this player starts to play the element and keeps on until this player and the next number is again indicated. Thus, an element once started goes on "automatically" when playing. This also has the practical consequence that the piece may be played from one copy which is simply handed over to the next player after reading the element to play next.. In the score, a sequence of different elements with their starts and new elements is indicated. The notations need not be understandable to everyone - it is enough that each player can remember its meaning and correctly reproduce it later.

As a collaborative exercise, one can mimic this compoisitonal strategy with friends. Find a piece of paper and some friends, and each grab a coloured pen. Write a musical phrase or draw a picture that might inspire you, and pass it on to create your very own composition. The beauty of this piece is that any paper will do: the one pictured above is written on the back of a Natural History Museum paper bag.

Here is a performance by the 6daEXIT Improvisation Ensemble. There are ways in which the Shogi methods expands the neurotypical range—or makes space for neurodivergence at a formal level. See also Nomura’s “Improvised music by autistic people.”

18. Gyorgy Ligeti’s “Nouvelle Aventures”

A page from the score to his Nouvelles Aventures (1962/65)

Ligeti fled Budapest in 1956, after the failed Hungarian uprising against Soviet control, and found himself in West Germany, in the center of a musical avant-garde overseen by Stockhausen. It was this experimental scene that put Ligeti in dialogue with his peers, as Thomas May describes:

Berio’s and Cage’s experiments both with the voice and with making the ritualized performative context part of their composition process captivated Ligeti. As in Sequenza V, the musical scores – the sounds specified – for Aventures and Nouvelles Aventures are only one layer of a larger scenario that also involves an absurdist theatricality of gestures and interactions. Ligeti even invents a nonsense language based on vowel sounds for his “text” as the singers enact an incoherent drama among themselves, a mini-opera (or anti-opera) of the absurd. Instead of playing a triangle of distinct characters, they are possessed by arbitrary mixtures of five general emotional positions (which Ligeti describes as ranging from aggressive desire to terror). Their abrupt, jittery, indecisive leaps from one to another are articulated in a kaleidoscopic vocabulary of sustained pitches, whispers, erotic grunts, shrieks, giggles, and so on, shattered by eerie silences. The effect at times is of listening to animal vocalizations at the zoo and trying to decipher what is being communicated.

Ligeti breaks off the Aventures (composed in 1962 and premiered in 1964) unexpectedly. The Nouvelles Aventures (written over the next few years and premiered in 1966) presents itself as “the sequel” but involves a subtle evolution of the scenario. Whereas the earlier “mimodrama” (Ligeti’s term), for or all its outrageous humor, evokes an existential, alienated sensibility, the two-part Nouvelles Aventures ironically introduces stylized historical references and more episodically defined subsections: a haunting fragment of a chorale, for example, and even a “grand hysterical scene” for the soprano to pose as a mad bel canto heroine. The framework provided by the instrumental accompaniment – which includes furniture and popped paper bags in Aventures – provides an even more wildly intrusive and absurd aura in the sequel, marked by violent climaxes such as the smashing of plates.

I love Stefan Beyst’s thinking on composers, poets, and artists—”Ode to the discrepancy between word and deed” is Beyst’s take on this piece.

19. Luciano Berio’s “Sequenzas”

To push every instrument to its breaking point—that was Berio’s working concept with the his fourteen “Sequenzas” for solo instruments. Considered some of the most difficult pieces to perform, the sequenzas are titled after the Italian word for “sequence.”

I excerpted Berio’s note for “Sequenza III” above—written for Cathy Berberian. And there is more on Berio’s website.

20. Heinrich Ernst’s “Variations on The Last Rose of Summer”

Henrich Ernst’s transcription of Thomas Moore’s poem, “The Last Rose of Summer,” is a fascinating example of polyphony in 1864. The techniques required are not only at the very extremes of the violinist’s capabilities, but also required at the same time as one another. I love seeing how a poem finds its way into a score—and how it is changed by this.