And then re-read it in light of Vollmann’s end-notes. To note—Vollmann populates his end-notes with so many riches and keys to the text. I never skip them.

Microscript 131, April, 1926 by Robert Walser.

Robert Walser's Microscripts.

Robert Walser made use of the miniature form in his Microscripts — tiny embodiments of the miniscule. The microscript form came to Walser as a result of a writer's cramp, which he qualified as: "a swoon, a cramp, a stupor - these are always both physical and mental." His formally ornamental scripts turned tiny, microscopic, using pencil rather than pen, breaking with what translator Susan Bernofsky calls "the aesthetic ideal of the elegantly inscribed page."

The Microscripts are written on found materials which make the texts look like collages, modernist mashups toeing the line between mechanical and personal production.

In English, the gloss is often taken as a form similar to the interlinear gloss of medieval text or marginal comments (as one sees in Coleridge's the Ancient Mariner). In the introduction to Robert Walser's Microscripts, translator Susan Bernofsky describes the satirical gloss as a well-known form in German literature, popularized by Karl Kraus. One thinks of Robert Musil—who loves them – and Walter Benjamin, who seems to be influenced by them.

W. G. Sebald called Walser "the clairvoyant of the small," and Walser took this smallness literally as his handwriting got smaller and smaller over the course of his career. He even squeezed out a final short novel, The Robber, on 24 sides of octavo-size paper in what scholars believed to be a secret, uncrackable code.

Nothing remains from Walser's final years in the institution, the asylum where he died and disappeared.

Here is one of Walser's microscripts as translated by Bernofsky.

Image source: The Improbable

Maira Kalman’s illustrations and notes are also marvelous, and they exist in dialogue with Walser’s biography. They are captions for glosses—-or glosses on images.

The gloss form is still fantastic, and it’s defined as a brief notation, especially a marginal one or an interlinear one, of the meaning of a word or wording in a text. It may be in the language of the text or in the reader's language if that is different. Here is the wikipedia:

A collection of glosses is a glossary. A collection of medieval legal glosses, made by glossators, is called an apparatus. The compilation of glosses into glossaries was the beginning of lexicography, and the glossaries so compiled were in fact the first dictionaries. In modern times a glossary, as opposed to a dictionary, is typically found in a text as an appendix of specialized terms that the typical reader may find unfamiliar. Also, satirical explanations of words and events are called glosses.

The dedication, itself, reads like a prose poem, or suggests an epistolary.

Short lesson on craft from William Maxwell.

I will begin with a scowl.

William Maxwell's short story, "The Pilgrimage," grates my nerves. It revolves around an American couple in France trying to get to a restaurant their friend said was the best, and the drama of their pilgrimage - how they call themselves pilgrims - and their outrage over menus and changes in the offerings, all mixed with a ton of fancy dishes, flat dialogue with waiters, chunks of an untranslated decorative French – and a dance scene at the end which is supposed to convey happiness. The Americans dance in the street. Frankly, it's not that interesting. It’s not his best work, yet it gets read more often than his incredibe stuff—which is probably due to over-identification on the part of the American reading audience.

I do love William K. Maxwell’s writing. The one I love most is a lesser-known collection of short stories, or fables, titled The Old Man at the Railroad Crossing and Other Tales. Maxwell dedicated the book to Em, his wife. In the preface, he explains that many of the stories grew from tales he invented for her on sleepless nights.

The compositional method began with the first sentence: “The first sentence was usually a surprise…From the first sentence, everything else followed.”

Structured as fairy tales, many begin with that lingustic frame, as in “Once upon a time there was a man who had no enemies, only friends.”

Or: “Once upon a time there was a man who lost his father.”

And: “There was an old woman whose house was beside a bend in a running stream.”

Or else they phrase the problem at the outset, as in “Not everybody’s heart and mind reside in this body.”

The table of contents, itself, feels like a writing prompt—and I play a fun game where I attempt to match the first line to the title, to trace the tale’s costume to the thread.

“There are things that cannot be said except in a roundabout way,” Maxwell fables, “and things that cannot be done until you have done something else.” So in country where pigs bury their thoughts in hay, everybody has a special relationship to the hayloft, or to their knowledge of it. In a country where it only rains on Sundays, no one makes plans to host picnics on Sundays. Each fable creates a world by describing its peculiarities—or limitations. These are rules. And we can create entire stories by beginning with a rule about a world. The birds eat all the bells. The queens are actually kings. The creek is a highway to hell.

Borrowing from oral storytelling traditions, Maxwell changes the frame by adding explicative statements like “This is not as strange as it first seems..” or “One might have supposed that…”

To express the characters’ alienation from time, Maxwell gives us an image: “Every year the earth grows more out of touch with the sky.”

Here’s an excerpt from “The lamplighter,” one of my favorite stories in this collection—to give you a sense of the language and texture, the structure of the sky and time (see “coda”), and the anachronstic character of the lamplighter.

A large view of the boulevard feels grandiose and magnificent unless all the streets are boulevards, and all the views are large ones, in which case the magnificent grows monotonous. The strange is the storyteller’s best friend. A few writing games for those who love words and language—

Game 1

Write a brief tale titled after one of Maxwell’s stories as listed in the table of contents. Make the first sentence a surprise. Consider using an enchanted object. Develop your images by focusing on strange metaphors and fabulist time.

Game 2

Write a brief fable that begins with the statement: “Twice upon a time…” Let an object be the narrator.

Game 3

“Ahoretia” is the malady of lack of determination. Write a vignette about a character suffering from ahoretia who has gone to see a therapist for help. Let dialogue drive the story. Play with misunderstanding, or the absence of a shared daily world in which the protagonist attempts to create this world for the therapist, only to be met with the therapist’s world.

Booklist for writing the uncanny details

Brutality hides inside banality—beneath the ironed uniform, under the cassock of the priest, in the starched business decorum of the professional—the monstrous is made even more monstrous because it looks safe, ordinary, appropriate.

"Germany declared war on Russia. Went swimming all afternoon."

Franz Kafka in his notebooks

This juxtaposition is horrifying precisely because it is banal. It reveals how life goes on as usual in the middle of tragedy, in the space after losing a loved one, in the hollows of genocide and wars, in the sunshine that greets a patient leaving the office where she has been given three months to live. The brutality of the ordinary assures us that life continues like a machine without us.

*

Brutality, banality, the screwiness of what is familair—and how certain writers have used fictional techniques that play into estrangement. I’m teaching a weekend workshop for Bending Genres (you can sign up for the asynchronous here)—and a weekend doesn’t give us adequate time to do more than dabble through excerpts and short readings. This makes me nauseous in some ways—nauseous because these books are formidable and deserve so much more than a dibble or a dabble.

So I created a booklist for writers who want to study the uncanny weirdnesss more closely—to get a deeper glimpse of the extraordinary, duplicitous banality in modern language. All of these books will be touched upon, or licked a bit, in the workshop. I hope that others find time to do more than to lick, which is to properly masticate and devour.

Not an exhaustive, but a tasty start.

The Promise by Silvina Ocampo, translated by Jessica Powell & Suzanne Jill Levine (City Lights Books)

The Voice Imitator: 104 Stories by Thomas Bernhard, translated by Keith Northcott (University of Chicago Press)

The Collected Stories of Diane Williams by Diane Williams (SoHo Press)

Bessarabian Stamps by Oleg Woolf, translated by Boris Dralyuk (Deep Vellum)

Nadirs by Herta Müller, translated by Sieglinde Lug (University of Nebraska Press)

The Encyclopedia of the Dead by Danilo Kiš, translated by Michael Henry Heim (Northwestern University Press)

A School for Fools by Sasha Sokolov, translated by Alexander Boguslawski (NYRB Classics)

On Being Blue: A Philosophical Inquiry by William Gass (NYRB Classics)

The World Goes On by László Krasznahorkai, translated by George Szirtes, Ottilie Mulzet and John Batki (New Directions)

The Complete Stories of Leonora Carrington by Leonora Carrington (The Dorothy Project)

Do Everything in the Dark by Gary Indiana (ITNA Press)

Empire of the Senseless by Kathy Acker (Grove Atlantic)

We Others by Steven Millhauser (Knopf Doubleday)

Microscripts by Robert Walser, translated by Susan Bernofsky (New Directions)

The Walk by Robert Walser, translated by Susan Bernofsky and Christopher Middleton (New Directions)

For writers trying to learn the genre known as the "pitch."

There is this thing called a “pitch” or a “query form” that can be daunting. I say this as someone who has yet to query an agent because the pitch itself is daunting to me.

Here’s a great how-to example from Cassie Maines, an agent and writer with Howland Literary Agency.

Eric Smith has devoted an entire page to the variants of this genre on his blog, including notes on why talking about yourself in relation to other authors may be a mistake. Smith also includes a fabulous list of twitter authors and agents who regularly spend time discussing the system and how it works.

On the book review side, Adam Morgan compiled a long list of sources and references which is right here. And there is a related twitter thread filled with helpful comments from book critics, including this one:

All this is just to say: twitter often serves as a resource for writers reviewing books and looking for agents. Don’t be afraid to engage the generosity of twitter literature community, especially if you don’t have personal access to publishers.

"The world is no place for poets": Notes on infra-noir and Romanian surrealists.

Initially, I had planned to be an alchemist.

This is what my Romanian father said when I asked him why he became a metallurgist. The esoterics of alchemy inflect Romanian poetics, particulary that of the interwar avant-garde movements.

The desire to create an immortal metal exists in poetry as well as science. The poem changes forms in translation, acquires the burden of new borders, new customs, new contexts that the foreign reader can't access. I've been wandering through Romanian surrealism lately, and leaning into the alchemical in a recent series of poem-dialogues with the poets of the interwar period.

The backstory matters.

WHO IS GHERASIM LUCA?

Born in Bucharest in 1913 as Zollmann Locker, Gherasim Luca was a Romanian Jew who survived the Antonescu's fascist Iron Guard regime only to flee the rise of the Communist regime for Paris in the 1950s, where he helped to found the Romanian Surrealist group, an assemblage of un-Breton-like writers and artists who deserve more attention. (More specifics on this under Bucharest Surrealists.)

In 1931 and 1932, as neo-fascist nationalism gained ground in Romania, Luca worked with other Bucharest writers to create two ephemeral magazines with scandalous titles, namely Pula («Dick/Penis») and Muci («Boogers»), which were sent to some important personalities of the time, such as Nicolae Iorga, considered by many to be an intellectual apostle of nationalism. In response, Iorga called the police to arrest “the gang of the spoilers of writing”. So Luca and his fellow journal editors were were arrested and imprisoned for several days on the accusation of pornography.

Throughout the 1930's, Luca continued to publish his radical work in countless literary journals. where Ovidiu Morar says "he vehemently denounced the exploitation of the proletariat, the officially encouraged anti-Semitism, the fascist danger, and the increasingly threatening specter of the war, meanwhile sustaining the idea of an «engaged» (or «revolutionary») literature." He laid himself out as the primary theorist of "proletarian poetry" in a series of articles published in 1935 in the left-wing magazine Cuvântul liber.

Per Morar, Luca thought "proletarian poetry (which was opposed to the «pure» poetry, considered to be in the service of the dominant class) had to reflect the deep contradictions of the bourgeois society, in other words, the motor had to be the class struggle." The anti-bourgeois and anti-aestheticist tone of "Poem of the Gentle People" lays out the tension between exploiter and exploited so well:

I know at last the infamy of the gentle people

I know those people with wet and round hands, ready to caress everybody

I know also their thin and smiling lips that always have one or two words of pity, of caress

oh, thin and infamous lips, against which I should write all my poems

thin lips, smiling lips, made for touching the forehead, for saying a prayer

Luca ends this poem with the following warning:

comrades,

the robbers who break in the house at night to steal

are just as dangerous, either masked or with uncovered faces

their masks, their smiles, their words of priest and god

must be once for good unmasked

THE BUCHAREST SURREALISTS

In 1938, Gherasim Luca left for Paris, where he met André Breton and other members of the French surrealist group, but the outbreak of the war forced him to return to Bucharest, where he settled, together with Gellu Naum, forming what would later be known as the Bucharest surrealist group (the other members were the poets Paul Paun and Virgil Teodorescu, and the painter Dolfi Trost). Otherwise, the adverse political context (the setting up of Antonescu’s fascist dictatorship and his alliance with Hitler) forced the group to suspend its activity by the end of the war (besides their communist sympathies, Luca, Păun and Trost were Jews).

The Bucharest Surrealists were active between 1940 and 1947, and they openly critiqued Breton's Parisian surrealists for giving up on revolution in the name of a dicta, a replicable formula or style that put value in the repetitious techniques as avenues for truth rather than revolt. Fijalkowski notes that the Bucharest surrealists were mostly writers, and the painters connected with them, Brauner and Hérold, spent this period in France.

The group would explore a range of explicitly anti-aesthetic (in Luca and Trost’s words, “aplastiques, objectifs et entièrement non-artistiques” ‘aplastic, objective and totally non-artistic’) visual practices. Notable among these was the domain of the object, developed in particular by Luca during the early 1940s with his notion of the “Objectively Offered Object,” a game in which found and constructed objects might act as lightning rods for interpersonal exchange, sorcery and divination; Luca’s account of this experience Le Vampire passif is illustrated with a number of such assemblages. (1)

November 1940 saw a huge earthquake in Bucharest (which Luca described in The Passive Vampire), so collapse was always part of living, creating, divining for him. The architecture of existence resembled the fractures of a street during earthquake.

CUBO-MANIA

Around August 1944, when the fascist wartime regime fell apart in Romania (a topic that deserves an entire book) that Luca came up with his method of "cubomania":

A collage in which source material is sliced into precise squares and reassembled as small grids of tessellated papers, its formal economy masks an ambitious conceptual framework that makes the process not only unique within surrealist collage practice but also one of the most theoretically-driven instances of surrealist image-making. Two exhibitions in Bucharest, in 1945 and 1946, and a pair of small publications – one, Les Orgies des quanta, devoted exclusively to the cubomania – presented the first results to the public.

The war wasn't over. The catastrophe changed shape and continued. Luca, himself, had been forced to work as a street cleaner, clearing away rubble and bodies after bombardments. (Note to self: a link between this and Antoine Volodine's rubble-cleaner as a form of metaphysical and social innocence.)

Statements co-authored with Dolfi Trost in 1945 insist "their visual works, far from constituting an artistic practice of the kind that Dialectique de la dialectique critiqued, should be read as the visible signs of a revolutionary theoretical program." 1945 also saw the publication of The Passive Vampire, where Luca defined the objectively offered object as "an object made while thinking of the person to whom it was intended," allowing it to serve as a vehicle for intimate or intellectual exchanges which can be reinterpreted, almost an icon, a space for apocalyptic thought. (See, for example, "Le lettre L".)

"We agree with dream, madness, love, and revolution," they wrote, against class and poverty and death. Towards delirium, weeping, somnambulism, the concrete,the absurd, desire, hysteria, furs, black magic, "the dialectics of the dialectic", simulacra, flames, vice, "objective chance," cryptaesthesia, and bloodstains. Towards ecstasy. Towards a permanent revolutionary state, Luca said, "The cubomania denies. The cubomania renders the known unknown." It negates the images that oppress us, and one can discern a critique of consumer culture and the modern nation-state in this, I think.

Late nineteenth century engravings, reproductions of early twentieth century academic or impressionist-style paintings, and contemporary mass-media photographs of nudes, the three sources of the cubomanias of the 1940s, together span an era of the previous fifty years whose structural integrity had failed (Luca’s project echoing in more violent and pessimistic form Walter Benjamin’s archaeology of the outmoded fragment or ruin).

And Morar translates Luca's statements on cubomania from Inventatorul iubirii:

this vibrating mixture of fragmented women, unknown or partially known, and that are attracted to me with an irresistible force, in circumstances without equivalence in the ready-made world of the current or exceptional phenomena, but that remind sometimes of the processes of displacement and condensation suffered by the phenomena of the dream life.

These bodies of women dynamited in me, fragmented and mutilated by my monstrous thirst for a monstrous love, have at last the liberty to search and find outside the marvelous from the bottom of their being, and nothing will make me believe anything but the fact that love is this mortal entrance in the marvelous.

INFRA-NOIR

In January 1945, Dolfi Trost and Gherasim Luca exhibited their mixed media work. One month later, a similar mixed media surrealist exhibit featured Paul Păun's work.

But the big date was in the fall of 1946, when Infra-noir happened, including work from Dolfi Trost, Gherasim Luca, Paul Păun, Virgil Teodorescu, and Gellu Naum. The text they selected to represent this event, "Chercher le triple sur les ruines du double" ("Seek the triple on the ruins of the double"), spoke directly to the desire to negate its own negations:

Infra-noir was initially intended to be an international survey of surrealist art, an ambition frustrated by the precarious state of communications in Europe at that moment, and there is a sense in which the works on display, and the cubomania in particular, not only had to stand in for those from the absent international movement, but already to start the work of their inevitable critical dépassement.

Significantly, the group’s contribution to the 1947 International Surrealist Exhibition in Paris was not with artworks, but with a text proposing a great, pitch- black room in which to encounter unknown objects (Luca, Naum, Păun, Teodorescou, and Trost, “Le Sable nocturne”). After the war, however, Luca continued to pursue a number of visual experiments, such as fragile and meticulous drawings constructed from constellations of dots, and intriguing text/image dossiers in which found albums of photographs were re-energized by new poetic captions.

Unlike Tristan Tzara's sarcastic absurdism and near-nihilism, the Bucharest group thought randomness- for-randomness' sake was fruitless; their approach was both critical and dialectical procedure. When Tzara and his friends visited Bucharest in November 1946 for the Infra-Noir, Luca and a few others sent him an insulting letter saying as much. I think of ceremony and play, using dialectic to negate the negation, the revolt against perception could be seen and applied to consumerism. I think of the grave yard stickers on the backs of trucks and cars.

The surrealist commitment to epistemological rupture carried an ontological component for the Bucharest surrealists. In 1947, Luca carried the Infra-noir further with Le Secret du vide et du plein: "Replace the real by the possible and anticipate their confusion . . . To forget forgetting, to triple the double, to void the void, is to invent plenitude in its movement."

Luca married Micheline Catti and collaborated with her. He stayed busy in Paris; he stayed in the orbit of artistic happenings, including his presence in Fluxus events like the Festum Fluxorum, Paris December 1962, or the 1957 painting Bouquet made in collaboration with Beat poets Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, and Peter Orlovsky.

Also, to quote Morar again:

Another, more tentative, source with Romanian connections – not that Luca would have cared for enquiries along such nationalist lines – is a photographic album by Benjamin Fondane from the 1930s, in which either rational or arbitrary selections of images are arranged in loose, playful grids on black backgrounds. The album has only recently become known through its inclusion in the exhibition and catalogue La Subversion des images (Bajac 206-07), but it seems plausible that, as fellow expatriates and friends of Victor Brauner, Fondane and Luca may have discussed the work during the latter’s stay in Paris at the end of the 1930s. (2)

42 INFRA-NOIR OBJECTS

All of this, perhaps, is the context for my poetic series, 43 Infra-noir objects, which draws on collage forms. Each object contains traces from the writings of those who participated in the Infra-noir exhibit. Rather than invoke these ghosts by name within the poem, I engage them in the ruins of their own words, in the collision and collapse of meaning, in the images that continue to divide us.

I am grateful to Poetry at Sangam for giving these three untitled pieces from the series a home—and to Priya Sarukkai Chabria, for making space for them among the other fascinating voices.

END-NOTES AND ADDENDA

(1) Fijalkowski, Krzysztof. "Cubomania: Gherasim Luca and Non-Oedipal Collage." Dada/Surrealism 20 (2015): n. pag. Web. Note also collaborations with artists were a notable aspect of Luca’s activity from the 1950s onwards, and his books featured contributions and exchanges with figures such as Victor Brauner, Jacques Hérold, Matta, Max Ernst, Wifredo Lam, Jean Arp, Dorothea Tanning, and above all with his wife Micheline Catti.

(2) Ovidiu Morar looks at Deleuze's love for Luca, particularly the stutter of the "schizoid-revolutionary" as opposed to the "paranoid-fascist", the reading of which is very common right now. He brings in the poem, "Niciodata destul," or never enough, which developsfrom phonemes and fragments in the word "proportional", which Lucas decomposes and subverts against nationalism, anti-semitism, and war. "popor" and "prop" get close, the last line being "de popor proportional."

(3) Veronica Porumbea was also a Romanian-Jewish poet. Unlike Celan, she had no trouble following Party lines in her writing. She worked as a translator and stayed publishable throughout. And there is the romance of prisons, perhaps, the way my heart assumes what is imprisoned is always the goodness, the lone voice – and what is criminal is the system, those who run the Writers Union, who owned the arts funding, who tell us that natives should be valued over immigrants. The risk of power— the risk of being at the top—comes with purges.

"Revenge" by Diane Williams.

From The Collected Stories of Diane Williams, published by Soho Press in October 2018.

"LASS / LET" by Aria Aber.

Lass, which could mean many different things in English: sweetheart, young girl, a feminine darling. In German, it only means to “let” something happen...

The line that has carried me through my nights, companioned or no, my lyrical creation myth, begins as an imperative in both languages. It supposes obedience, wants to instruct. Like a master, this word heralds into the room with agency, with an agenda. Rilke wrote, “God talks to us before he makes each one of us”—what tameness brought him there?

Gott spricht mit jedem von uns ehe er in macht—

Rilke wrote The Book of Hours in Russia, where he was startled by God's presence. Like Nietzsche before him, Rilke thought God to be pantheistic, all-encompassing.

Marina Tsvetaeva said of Rilke that he was pure; poetry incarnate; that he was the only clean, and cleansing, soul among war-destroyed Europe, because his poetry refused to acknowledge that terror.

My mother let me happen to her. She let prison happen to her, simply because she believed in Women's Rights and Afghanistan as a sovereign state. She went to prison with her little sister, and she emerged. She was, I can say now, a political prisoner. She let it happen to her; then she decided to leave her family behind, move on for love, for family, for me.

This sacrifice let her become monstrous. She let monstrosity happen to her, then offered it back to me. When I ask, “God, who am I?” am I not just asking, Mother, who are you?

Let me rephrase this—are there any mothers that aren't cruel, perverse, unbelievable?

Rilke's mother, to this day, is called “perverse” and “unbelievable” by many male critics. She is ostracized, her own monster. She was a woman, she had her tics. She had opinions.

Rilke, who writes as neither man nor woman, is influenced mostly by God. Rilke loves God endlessly 𝑢𝑛𝑑 is not ashamed of it. Brecht called his relationship to God “gay.” I like to believe Rilke wouldn't have cared, would have said: “Let me be gay with God, then.”

As Ulrich Braer puts it, Rilke's God wasn't a fascist or heterosexist; he simply was, encompassing both the finite feelings of physical intimacy and his Drau fensein, his being-outside.

The transitive verb 𝑙𝑒𝑡 supposes danger; it is aware of the other, like paranoia. It is influenced by the other, only exists in relation. Let is only summoned when we want to be done away with: let me do this.

Meaning: give me permission. Let this happen to you. Let it go.

Meaning: I give you the permission to abandon it. Let me go outside!

Let me be

everything that happens to you.

A list of prose poems to explore.

Alejandra Pizarnik, “Sex, Night” (trans. by P. Ferrari & Forrest Gander) ^

Alexander Long, “Meditation on a Suicide”

Alina Stefanescu, “Hush Hush Hush” and “Two Faces”

Amaris Feland Ketcham, “How We Echo”

Amelia Martens, “A Robin Pulls a Thread”

Amorak Huey, “Prayer for What I Do Not Want”

Ann Waldman, “Stereo”

Anne Carson, “Short Talks” ^

Aria Aber, “Lass/Let”

Arthur Rimbaud, “First Evening” (translated by Kline)

Beckian Fritz Goldberg, “Past Immaculate”

Beckian Fritz Goldberg, “Enchanted Egg, #2”

Beckian Fritz Goldberg, “He Said Discipline Is the Highest Form of Love”

Beckian Fritz Goldberg, “Afterlife”

Beckian Fritz Goldberg, “The One with the Darkest Hair”

Ben Miller, “The Opposite of That Famous Story”

Bob Hicok, “Prose Poem Essay on the Prose Poem”

Brenda Hillman, “Childhood” - an essay in rhyme

Cameron Awkward-Rich, “Meditations in an Emergency”

Campbell McGrath, “The Prose Poem”

Carol Dorf, “On the Way Out of Memory Palace”

Carol Guess

Cecilia Woloch, “Postcard to I. Kaminsky from a Dream at the Edge of the Sea”

Charles Rafferty, “The Problem with Sappho” ^

Charles Simic, “Heroic Moment”

Christopher Kennedy, “Personality Quiz”

Christopher Kennedy, “The Genius”

Claudia Rankine, 2 poems from Citizen, I ^

Czeslaw Milosz, “Decency”

Daniel Poppick, “The Apple’s Floor”

Daniel Romo, “Attention”

Danielle Mitchell, “Year of the Dig”

David Daniel, “Paint”

David Daniel, “Hotel”

David Ignatow, “Forever”

David Ignatow, “Information”

David Keplinger

David Shumate, 3 prose poems

Deborah Digges, “Fence of Sticks”

Denise Duhamel, “Napping on the Afternoon of My 39th Birthday”

Denise Duhamel, “Infiltration”

Denise Duhamel, “The Drag Queen Inside Me” ^

Denise Duhamel, “Permanence”

Diane Raptosh, “Husband”

Dina Relles, “In A Sunday Kitchen”

Doug Martin, “Morning Sickness”

Emma Bolden, “Describe the Situation in Specific Detail”

Essy Stone, “Among the Prophets”

Fanny Howe, “Second Childhood”

Frank O'Hara, “Meditations in an Emergency”

Frank O’Hara, “The Eyelid Has Its Storms” ^

Gabriel Gudding, “A Defense of Poetry” ^

Gary Young, “Four Poems”

Geoffrey Dyer, “Tuesday, April 11, 2006”

Geoffrey Dyer, “Wednesday, January 26, 2006”

Gian Lombardo, “On the Mark”

Gian Lombardo, “Three Wishes”

Howie Good, “Door to the River”

James Tate, “All Over the Lot”

James Tate, “Goodtime Jesus” ^

James Wright, “Honey”

Jane Harrington, “Ossein Pith”

Jayne Anne Phillips, “Happy”

Jean Follain, “Prose Poem” (translated by William Matthews and Mary Feeney)

Jennifer Givhan, “Domestic” ^

Jennifer Martinelli, “The Devil Tides”

John Ashbery, “The Young Son” ^

Kellie Wells, “Desertion”

Laird Hunt, “Michiko and Akiko”

Lance Larsen, “32 Views from the Hammock” - list poem

Lawrence Goeckel, “The Last Days Before the Age of Industry”

Layli Long Solider, “Introduction” - docupoetics

Layli Long Solider, excerpt from “Whereas”

Lucy Ives, Three paragraphs from The Nineties

Mark Strand, “Dream Testicles, Vanished Vaginas”

Mark Vinz, “Letter from the Cabin”

Mark Yakich, “The Ordinary Sun”

Mark Yakich, “The Mountain”

Marvin Bell, “About the Dead Man, Ashes and Dust”

Matthew Rohrer, “Disquistion on Trees”

Maxine Chernoff, “The Sound” ^

Maxine Chernoff, “Simple Gifts”

Maxine Chernoff, “Subtraction”

Mary Ruefle, “On Twilight” ^

Metta Sama, “Outlaw”

Mia Ayumi Mamalhotra, “On the street where a certain democratic leader lives…” ^

Michael Benedikt, “Three Sensualities”

Naomi Shihab Nye, “Hammer and Nail”

Nathan Parker, “Choice Pines”

Nicole Sealey, “Even the Gods”

Nin Andrews, “Adolescence”

Nin Andrews, “The Magic of Forgetting”

Nin Andrews, “How to Deal with Rejection”

Nin Andrews, “1967”

Peter Davis, “Poem Addressing Boys, Age 5”

Peter Davis, “Poem Addressing People Who Are Tired, Hungry, or Horny”

Randall Horton, “After Ruin”

Ray Gonzales, “Who Were You?”

Ray Gonzales, “I Saw” -a list of objects

Rob Carney, “Movie Review”

Robert Haas, “My Mother’s Nipples”

Robert Hill Long, “Doing Hatha Yoga”

Robert Lopez, “Man on Bus with Blindsters”

Ron Silliman, “Final For”

Rosmarie Waldrop, “The Material World”

Russell Edson, “Let Us Consider” ^

Russell Edson, “A Love Letter”

Sean Thomas Daugherty, “In the Light of One Lamp”

Sean Thomas Daugherty, “Two Variations on a Paisley”

Sean Thomas Daugherty, “Untitled” ^

Sho Spaeth, “Moods—Yoel Hoffmann”

Steve Berg, “Shaving”

Stuart Dybek, “Alphabet Soup”

T. S. Eliot, “Hysteria”

Terrance Hayes, “A Land Governed by Unkindness Reaps No Kindness”

The Cyborg Jillian Weisse, “My Friend Says I Should Be Thinking about “Masked Intimacy” When I Think about Leila Olive”

Tomas Transtromer

Yoel Hoffmann, “9”

Yoel Hoffmann, from Curriculum Vitae

Zach Savich, “Melon City”

Zach Savich, “Chestnut City”

Zach Savich, “Sheet City”

Zachary Schomburg, “The Fire Cycle” ^

Zbigniew Herbert, “The Wall” ^

And some books. Guide to Prose Poetry (Rose Metal Press) - Renee Gladman, Calamities (Wave Books) - David Shumate, High Water Mark (University of Pittsburgh Press) - Michael Benedikt, The Prose Poem: An International Anthology - Russell Edson, The Reason Why the Closet Man Is Never Sad (1972) - Arthur Rimbaud, Illuminations - Claudia Rankine, Citizen - Czeslaw Milosz, Roadside Dog - Frank O'Hara, Meditations in An Emergency (Grove Atlantic, 1957) - Mark Strand, The Monument (denied 1978 Pultizer Prize) - Top 10 prose poetry books according to Daniel Hales

"All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace" by Richard Brautigan

"Miss you. Would like to take a walk with you." by Gabrielle Calvocoressi

"Object Permanence" by Hala Alyan

This neighborhood was mine first. I walked each block twice:

drunk, then sober. I lived every day with legs and headphones.

It had snowed the night I ran down Lorimer and swore I’d stop

at nothing. My love, he had died. What was I supposed to do?

I regret nothing. Sometimes I feel washed up as paper. You’re

three years away. But then I dance down Graham and

the trees are the color of champagne and I remember—

There are things I like about heartbreak, too, how it needs

a good soundtrack. The way I catch a man’s gaze on the L

and don’t look away first. Losing something is just revising it.

After this love there will be more love. My body rising from a nest

of sheets to pick up a stranger’s MetroCard. I regret nothing.

Not the bar across the street from my apartment; I was still late.

Not the shared bathroom in Barcelona, not the red-eyes, not

the songs about black coats and Omaha. I lie about everything

but not this. You were every streetlamp that winter. You held

the crown of my head and for once I won’t show you what

I’ve made. I regret nothing. Your mother and your Maine.

Your wet hair in my lap after that first shower. The clinic

and how I cried for a week afterwards. How we never chose

the language we spoke. You wrote me a single poem and in it

you were the dog and I the fire. Remember the courthouse?

The anniversary song. Those goddamn Kmart towels. I loved them,

when did we throw them away? Tomorrow I’ll write down

everything we’ve done to each other and fill the bathtub

with water. I’ll burn each piece of paper down to silt.

And if it doesn’t work, I’ll do it again. And again and again and—

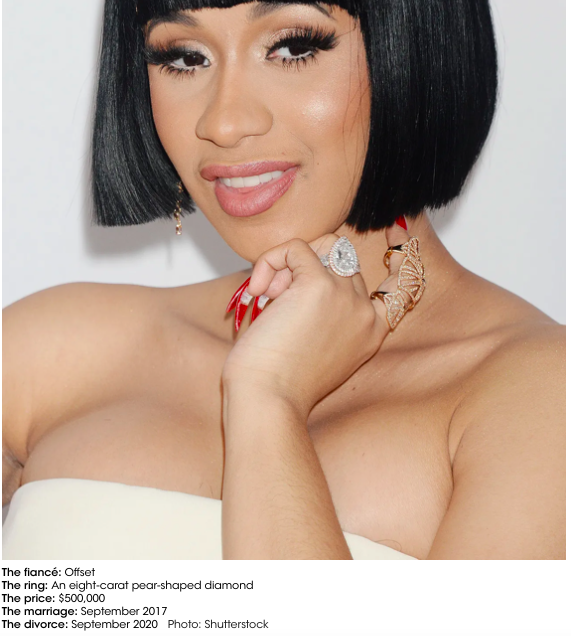

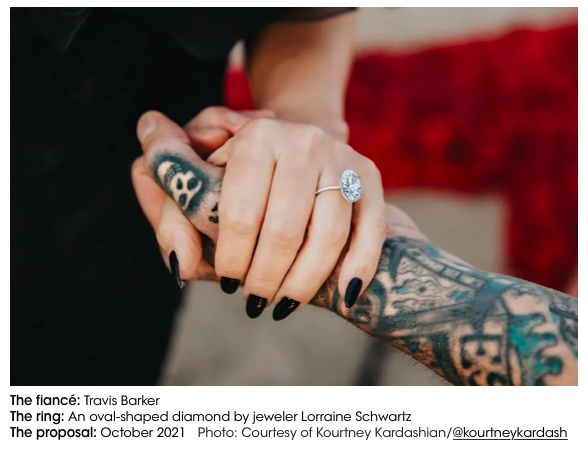

Diamond Media: A look at images.

YASMINE GHATTAS: Before World War II, only 10% of engagement rings had diamonds in them. After the Depression, no one was lining up to buy expensive goods. Americans had just been traumatized by one of the worst economic downturns ever and were stockpiling their money.

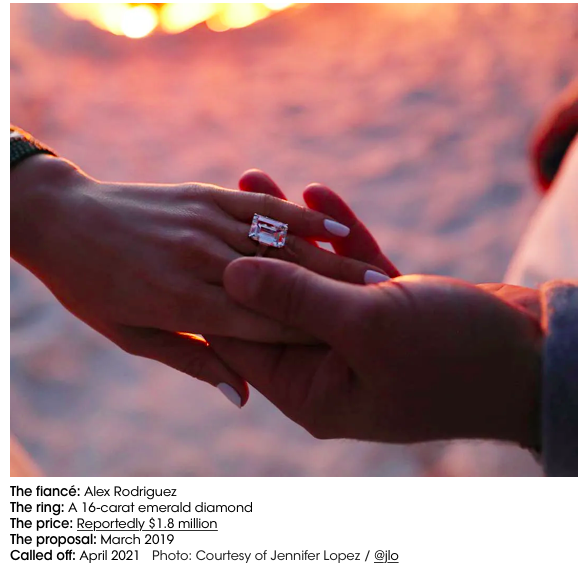

De Beers was quickly sinking in this economy, but they refused to sit idle. They had a stockpile of diamonds they needed to start selling, so they created a narrative around their diamonds. They wanted to equate diamonds with marriage — a pretty big ask. They started with simple celebrity marketing tactics. They would run stories of celebrities who wore diamonds, and more importantly, stories of those celebrities who had proposed with diamond rings. Fashion designers quickly started fawning over them and claiming diamonds as the new big trend.

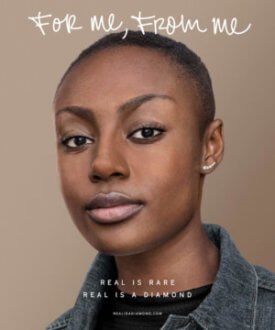

BUSINESS INSIDER: In 1947, Ayer creative Frances Gerety suggested the slogan "A diamond is forever." Both she and her colleagues weren't too excited by it, but they eventually used it in a campaign the next year. It immediately clicked with the American people, who soon began associating the gemstone with a fitting symbol of a promise of eternal love, rather than just an extravagant luxury. "A diamond is forever" has appeared in every De Beers ad since 1948, and Ad Age named it the best slogan of the 20th century.

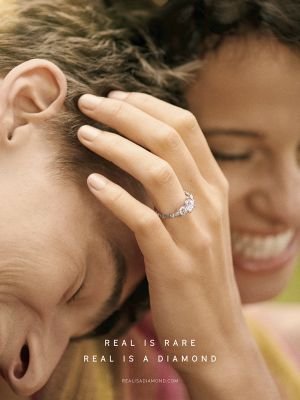

DEBORAH MARQUARDT, CHIEF MARKETING OFFICER OF DPA: The audience is given a glimpse into private ‘couple moments’ where the role of the diamond is intrinsic to the storyline, and is an expression of their love, their life together, and their commitment to each other.

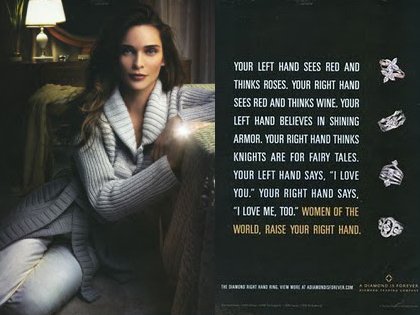

YASMINE GHATTAS: De Beers’ marketing managed to convince American men that to marry their dream woman they had to buy her a big old shiny diamond ring. They were marketing geniuses using simple psychology to conflate a product with an end goal. But for some reason, they weren’t able to do the same for women. In the 1980s, in an attempt to expand their audience, they started targeting women. Specifically, calling on women to buy their men diamonds.

5. Assuming you plan to get married some day, do you expect to either 1) receive a diamond engagement ring or 2) buy a diamond engagement ring? Why or why not?

ANDERSON & WEBB: So much has been written on diamonds, how to judge and buy, with issues of colour, cut and clarity, that it's hard to add anything new. So here’s a word for an unsung diamond hero, which rarely gets a look in the West, the polki diamond. Polkis are a prominent feature of Indian jewellery and especially wedding jewellery, where enormous stones are set in the most fabulously opulent of jewellery. Polkis are lower grade diamonds, almost of industrial quality for drills etc, but are sliced lengthways to form great swathes of gem, often with blacked oxidised finishes and foil underlay. So a very different look, at a fraction of the price of a polished stone, worth checking out to see if this is something you’d like to add to your jewellery box – I have!

TESS PETAK for Brides: So after searching for months to find the perfect ring without success, Vaughan decided to take matters into his own hands. He commissioned Kay Jewelry to help design a same-sex engagement and wedding band all in one. Vaughan had a major part in designing this ring (the initial sketch was done on his Poke bowl to-go container!). Still, it's important to note that this historic piece of jewelry marks one of the first same-sex engagement/wedding bands offerings by a major retailer.

BALLARD & BALLARD: “Men want to be on the foreground of a growing trend” -Unknown

Most people picture big, elaborate, sparkling, diamond rings when they picture an engagement. Most people also picture said ring on the bride to be’s ring finger forever changing her life for the better. Now what if we told you there was a ring just as elaborate or stunning sitting on the groom to be’s ring finger as well. In today’s changing world the topic of men wearing engagement rings has been brought to the forefront, and the numbers don’t lie. In recent years when surveyed, as many as 17% of men said they wouldn’t mind wearing an engagement ring. For some it might be just as flashy as their soon to be bride’s, but for others it’s something toned down from what their bride is flashing. This trend is going nowhere but up as men all across the world are wanting to be more involved in the wedding aspect of their lives.

THE PLUMB CLUB: Women are not only buying jewelry for themselves, they are involved in a majority of the engagement ring purchases and greatly influence gifting, says Neil Shah, a principal of Shah Luxury in New York City. He says the dramatic rise in customization services that his company has experienced in recent years is a testament to the significant increase in women participating in the jewelry buying process, because they know what they want. “And, we should be listening.”

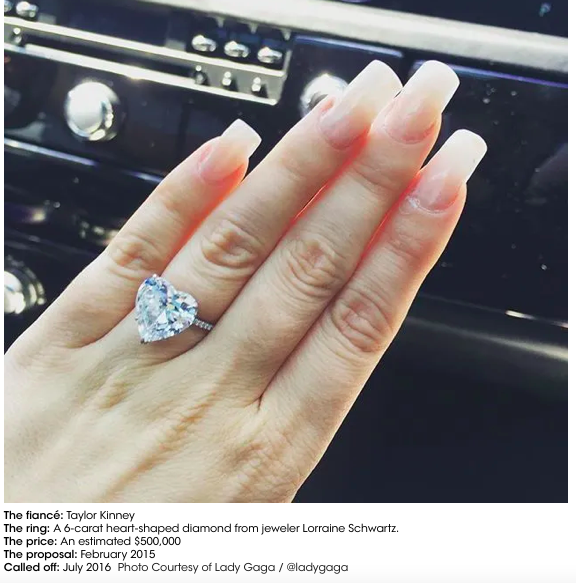

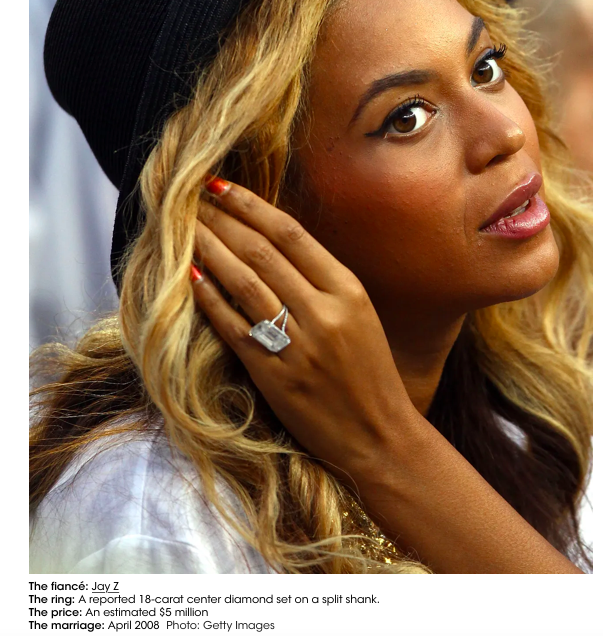

SUSANNE RAMIREZ DE ARELLANO: Beyoncé is the fourth woman and first Black woman to wear the famous gem — unearthed by De Beers in South Africa in 1877. The so-called Tiffany diamond was previously worn by Audrey Hepburn, Lady Gaga and the American socialite Mary Whitehouse, the first time it was paraded in public, at a Tiffany Ball in 1957. Tiffany & Co., which was recently acquired by the fashion conglomerate LVMH, hopes the campaign (together with a separate effort dubbed “Not Your Mother’s Tiffany”) will freshen and update Tiffany’s image for a new generation of luxury consumers. …The problem is the backstory of the yellow Tiffany diamond. Found in the Kimberley diamond mines in South Africa (under British rule) in 1877 as a 287.42 carat rough stone, it was later purchased by Charles Lewis Tiffany in 1878 for $18,000. Its estimated worth today is $30 million.

The poets with Appollinarian lineage.

I love discovering poems that invoke Guillaume Apollinaire as part of poetic lineage.

Maybe I also just love poems dedicated to dead poets, or what Jim Brodey calls the “greatest of predecessors” in his poem titled “To Guillaume Apollinaire” (which I found in a large yellow anthology edited by Andrei Codrescu in an earlier decade).

Revisiting William Stafford.

It’s been a while. I’d like to say it’s been too long, but the truth is that William Stafford reappears on a day when I needed him, in the outskirts of an autumn afternoon, at the edge of a song.

And song, itself, is central to Stafford’s verse—it recurs, returns, resurges, and sometimes revolts (as when the songs are national anthems or related to a war he refused to fight). “Why I Am a Poet” could be considered an ars poetica, or even an anti-anthem—three quatrains appended by a single line.

And the land is always palpable in Stafford’s poems—where the dirt exists in a mixture of wonder and humility. “Something That Happens Right Now” begins in a confessional tone that reaches towards a maple tree in the distant past, only to swerve into an expectant silence, a silence that precedes the adult’s knowledge of the world.

Death isn’t a terror so much as a wonder in this poem, in this unlineated creation bursting at the seams with marvel. I want to remember being young and feeling that cosmic silence, or feeling small and secure in it.

I will read this one to my kids tonight once the darkness arrives…to re-member the power of longing in a world that cautions us against it.

And one more. One more Stafford to tuck into a pocket, to carry through days when the words argue with one another and the images fizzle. One more for any writer today seeking “the great dance, walking alone”….

Annie Ernaux's use of italics in "A Man's Place."

In A Man's Place, Annie Ernaux says she uses italics:

"not because I wish to point out a double meaning to the reader and so draw him into my confidence -- irony, pathos and nostalgia are something I've always rejected. But simply because these particular words and sentences to find the nature and the limits of the world where my father lives and which I too shared. It was a world in which language was the very expression of reality."

A small collage of all the non-proper nouns Ernaux italicized in this text. I have added capital letters and periods where none existed, often to indicate words which stood alone in italics. I have preserved all the intact phrases and fragments and sentences. Where Ernaux italicized quotations and words by others, I have dropped the quotation marks and used italics.

We were happy in spite of everything. We had

to be. Had to live. Out of place. Nothing fancy, just

the standard thing. Eau-de-vivre. Galette des rois.

Town clothes. Patois. Lycee. In the fresh air. Elsewhere.

Bourgeois. There were others worse off.

For rolling in the dew makes the milkmaids so fair.

Brought home. Unprejudiced. Social outcast. What do you expect.

What are people going to say? Respected. Necessary.

Maintain his status. Position. All that. Good, clean

fun. Humble. Extended. I've only got one

pair of hands. Just as many things. The child has

everything she needs. Silly films. Luxury.

Wasn't as good. Too busy even to take a leak. Eat

into their capital. Think! You clumsy oaf.

There's no reason why you shouldn't go.

Despite everything one had to go on living.

Mademoiselle really had it tough

Better to be the head of a dog than the tail of a lion.

Widow of the late A------- D------.

Canton. Got on her nerves. Battled. Bad

manners. Walking, that's how I get rid of

my flu. Give a good talking to. Ditto. We all know

what's waiting for us. High-ranking.

Good manners. Concierge. Beat himself.

Or maybe hoped. To live. Enjoy life.

Impregnate. All that big business

ending up with a worker.

Do them any harm.

Oh, the hell with it, let's enjoy life while we can!

Honest, hardworking people half

set in their ways. Hired.

How's it all going to end

looked one up and down.

It’s a marvelous book. And I wanted to keep a record of the italicized words somehow. This is that.

Emmanuel Moses' "Prelude 4" and Fugue 4"

The following two poems, written by Emmauel Moses and translated by poet Marilyn Hacker, were first published in Modern Poetry in Review, No. 2, 2013.

A prelude (literally ‘before the play’) is a brief musical composition that is played before the main piece.

Preludes aim to capture small things or themes, and they tend to be short. Sometimes people think of them as thresholds, or entryways into the action of the longer piece.

As a form, preludes may even be written as practice pieces or exercises for performers—they tend to be shorter, and to explore a particular sound or element of composition. You can learn a lot about a composer by listening to their early preludes—and comparing them to later preludes.

When reading a poem that borrows this prelude as form, one might consider what ground or terrain is being staked out—who is the speaker, and what is the subject?

In addition to writing poetry and novels, Emmauel Moses translated writing from Hebrew, German, and English, and his father, Stephane Moses, was a noted philosopher and historian of Judaism.

Here is Moses’ “Prelude 4” as translated by Marilyn Hacker.

We did not ask to be born

to cross the first threshold

There is no punctuation here to mark the stopping points, or to delineate one image and thought from another.

In her translation notes, Marilyn Hacker emphasizes the relationship between history and music in Emmauel Moses' poems.

These poem are translated from Emmanuel Moses' book, Preludes and Fugues, which Hacker describes as "seven sequences of eight paired poems in which the second of each pair can be read as a fugal variation on the themes set out in the first."

Here is the fugal variation on the earlier prelude.

The references aren't always identified in Moses' poems—there are cathedrals, landscape paintings, city streets—and the reader senses them indirectly through the fleshing out of context, almost like learning to read, where you glean the meaning of a new word from what surrounds it. This indirect description is an interesting poetic strategy in Moses' work.

The speaker keeps moving—motion is a mode of questioning, of revisiting and reviewing—life in the shadow of the legible past. And the past is read into buildings, objects, and scenes—these function almost like texts here.

Hacker mentions how the speaker seems to be "an actor in one or a multiplicity of pasts." I think the fugue form aligns this polytonality, this sense of multiplicity, with the poet's intention.

The strange temporality of the speaker, and the "out of epoch"quality of these poems reminded Hacker of Jean-Paul de Dadelson's monologues in the persona of Bach and Marguerite Yourcenar's L'oevre au noir, with its jaded humanist scientist.

Who is "I" given the past, given the socialization, given the ways of being that shape us in the world? What does it mean to be out of one's time, and how does this correlate with being of all times, somehow?

A centro from Stella V. Radulescu's new poetry collection.

Traveling With the Ghosts, poems by Stella Vinitchi Radulescu. Orison Press, Dec. 31, 2021. 108 pp.

Although Stella Vinitchi Radulescu’s new poetry collection, Traveling with the Ghosts, has been called “impressionistic”, the first word that came to mind as I was reading was ethereal.

Orison Books has published Radulescu’s collected poems, and this book felt different—looser, more wistful, less grounded in sharp tonalities and colors. Yellow and blue recur. As do corpses, bones, and wings. The sky is both the vantage point and the sideline.

Samuel Beckett’s stark spirit hovers in the epigraph; the theme of a poet’s relation to the past is carried by ghosts of dead family and friends. Radulescu does not name these presences. Instead, she traces them in widening circles and repetitions. The speaker isn’t traveling with ghosts—she is traveling with the ghosts.

As a poet of open fields and particular punctuations, Radulescu doesn’t bring the closure of periods or the suture-marks of commas to these poems. The em-dash recurs, and functions as a colon to make space for expansion or qualification of what precedes it. The invocative direct address gives us a you that feels related to Romanian grammar—and which characterizesthe poet’s prior work—although this you draws nearer to something sublime, something divine, something that borders on the incredulous.

Alliteration creates a dialogue between titles and sounds inside poems. For example, the poem “invocation” repeats words that begin with a v, and “crossroad” repeats words that begin with a c, so that the chosen letter intersects with the key of the poem, itself. Radulescu has always been musical, and I read her for this, as well as for the estranged speaker, and the crackling syntax.

I loved this book, and the best way for me to explain this may be a cento, with one line taken from most poems, using only Radulescu’s capitalization and punctuation, maintaining her line breaks (though skipping the stanzaic divisions), stacking lines in the same order as the poems, and allowing the lines that held my attention to speak for themselves.

A CENTO WHO LONGS TO BE “TRAVELING WITH THE GHOSTS”

after Stella Radulescu

simple as death

to children of dust to children

I need a sentence to bring them

the violet eyes

the view is nothing but the flight

a word from which you could have died

a body alive or

the gloomy sky a noise like

the metaphor

of a new joy—

a flake of

a human shape of two entangled

squirrels & stars

on quiet pages:

hot inenscapable clock

the ancient house

in me

the lilac in blossom

the rhyme

of sweat & sweet

pouring from my chest

who knows the gender of time

the fire:

I fit in your eye

what else besides

a story

speaks loud and stretches

: the last drop of light

in the air

the shape of my tongue

the coffin on the grass

I feel like opening hundreds

wearing a yellow dress and

worms

from the ceiling hanging

like hope

the poem stands in front

of me

one foot behind the time

one more word for

chime—

would be a snake

the dead army seen from

ecstasy on the road to hell

ask me why

light keeps changing direction

& the flower

the rapture

a word can burn

a grave—

not mine

to be said twice

the tremolo

underground

an insomniac god

the sun &

tigers in cages are praying for me

who has blue eyes

like in a mirror

I am walking on snow as if

music from the bones

the agony of clouds

an apple

touching the earth is all the rain needs

a sky around

days

whose life exploded in the

want to repeat that?

we were in brackets we were

our secret language

the gate &

a pint of blood

a carcass left right here

rowing the silence

in my mouth