Speaking of fan-fic, pandemic, virtual schooling, balancing need for income with all the other attention the world asks of us, I’ve been reading many things I want to share but don’t have time to edit for submission. That is why I love this Five Things trope that Summer Brennan shared on her writer’s blog:

Back in the olden days of writing on the Internet, a group of writers I knew would often write brief essays or nonfiction blog posts structured around a list of “five things.” These “things” were usually observations, thoughts, confessions, referrals, or investigations. Each thing could be many paragraphs, or just one short sentence. I don’t know who originated the form. It might have been adapted from the fanfic trope of the same name, which goes back to the early 1980s, in which five scenes are presented from a story or relationship. It may also have come from LiveJournal blogs of the early 2000s, out of which emerged a popular type of entry called “five things make a post.” Or it may have developed separately, a kind of writerly convergent evolution, a carcinization of words, like how different animals keep independently evolving into the shape of crabs, over and over again in the dark depths of the seas. Creatures forged by the same environmental pressures. Regardless of where it came from, I found it to be a good way of getting thoughts down. There seems to be something about the number five that helps to give a satisfying structure, at least to the writer, if not to the reader. As I find my way back into regular online writing, I’ll be using it again here.

And I’m going to borrow it in the coming weeks… I’m going to leave lots of 5 things related to writing, poetry, intellectual “history,” nostalgia, longing, all the usual obsessions torqued to the key of pandemic-time. Or lack of time. A staggering lack of time even for night owls like me.

Starting with 5 things on conscience, community, and purity, everyone’s favorite afternoon topic, a space where I am working through thoughts and readings rather than constructing a theory or a position or following logic into some fantastic eschatology that mankind can use to justify the disappearance of Others.

1. The untenability of individual choice

“...the word conscience had gone out of ordinary use--it was not carried in newspapers, books, or in the schools, since its function had been taken over...by 'class feeling'. Kindness became something to be ashamed of..."

- Nazdheza Mandelstam's memoir, Hope Against Hope

Sometimes power looks like writing a poem that speaks into the space of damning others while ignoring how we live with the blood on our own hands. In Solzhenitsyn's Gulag, each prisoner confronts the choice of survival--how far will you go to preserve your own life? Often the choice is posed between losing one's life and losing one's conscience.

But we are all guilty. As women of the Confederacy were guilty, though they could not vote or exercise political power, we are all guilty of the crimes the US commits in the world. No nostalgia releases us from that. What I’m interested in, however, is the site where guilt and notions of purity converge.

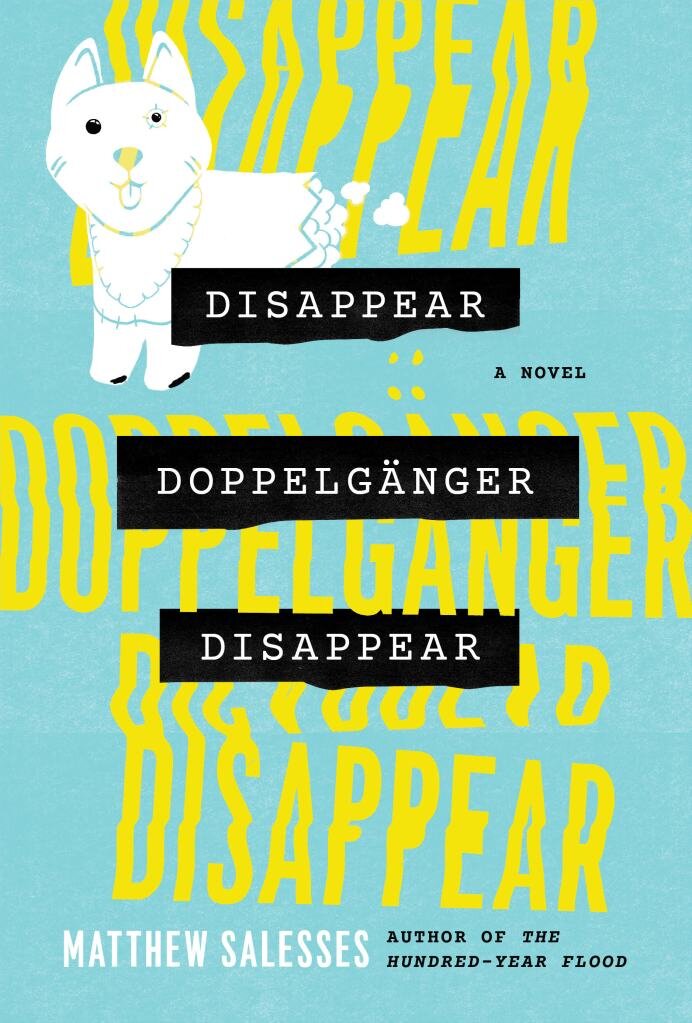

2. Matt Salesses’ doppelganger

I had been trapped by language ever since I thought it could save me.

- Matthew Salesses, Disappear, Doppelganger, Disappear

I think we hear the confluence of purity-trangressions in the voices of many cross-national adoptions, in differing pitches, valences, and degrees. In this novel, we see the disinheritances of assimilationist. The narrator reflects on the early death of his parents which led him to be adopted. Communication remains the most difficult thing for a Korean adopted by American parents. The narrator mixes their ashes together and throws them off a hill, remembering how they tried to fit in with local Chinese. His parents had been sure they would start life again with a triumphant return to their homeland but they died instead. We were as restless as regret.

And: I wanted us to get free of what we wanted-- his parents wanting a return and yet being thrown off a hill in a way they wouldn't have wanted.

Salesses refers to Korean belief that sleeping with a fan can kill you, and how this shocked is American daughter. How our homeland beliefs can be seen as ignorance. It is the alienation—the part where I remember being mocked for putting a hat over my toddler’s ears—of how traditions (read superstitions) are rendered impure, or situate one outside the shared knowledge of magic America.

To feel present, I think, is to experience other people sharing your experience.

And the narrator’s daughter, saying “ I envy you for feeling nostalgic about yourself when you were never that great to begin with.” The link between envy and nostalgia. Or, more broadly:

How memory fools desire. You slowly forget what is gone but never stop feeling its absence.

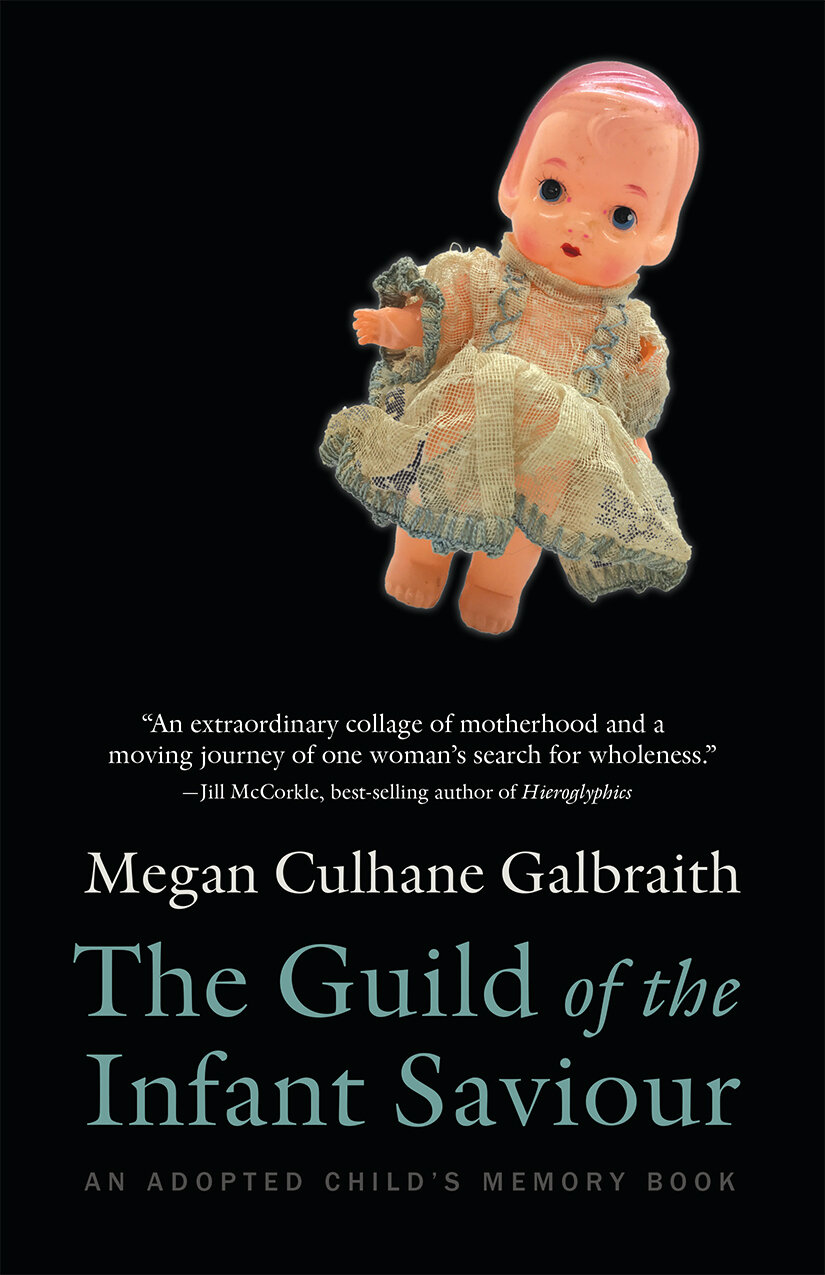

In one of several interviews with Megan Galbraith (whose own The Guild of the Infant Savior: An Adopted Child’s Memory Book is coming out this summer, which I anticipate) , Salesses mentions the English language's structural role in -isms, how "English grammar prioritizes subject and action over object and description (read: observation) - the idea that writers shouldn't use adjectives or write a 'passive sentence'." He uses jokes, puns, wordplay to subvert these priorities. Borrowed from Murakami how the protagonist has a very particular view of reality that others find outrageous, and conflict comes from reconciling existence.

The value we put on speaking up, on being heard and seen, can become a way of disapproving of the margins of the margins....The value of visibility depends on how we are visible and to whom and why.

This feels like a good argument against tokenism. The Iowa-style workshop functions best for poets who are writing into popular spaces, or accessible ones that rely on majority cultures and language. We believe that everything is political - that the poem is political – and yet our workshops assume that silence is respect and good sportsmanship rather than time wasted as people try to figure out the meaning of a word they could never have encountered. Beth Nyugen: "..a system that relies on silencing and skewed power and endurance is a terrible system." Or just a capitalist one.

3. Traitor to what, per when

I needed to write this book because as a mongrelized person, I feel personally threatened when everybody around me is seeking purity and certainty. I wrote the book I needed. The same impulse has guided me in these twenty odd years of writing; the audience has always been secondary. So many of us become writers because we need for certain books to exist that no one else is writing; especially, those of us who have migrated or have been dislocated. If you need a book to exist badly enough, you’ll write it. People who talk about writing, but never do, are not literally dying for that book’s existence; if they did, they would have written it.

- Mohsin Hamid in an interview about “denuding purity” with Guernica

For Mohsin Hamid, fiction exists as an imperative which makes space for his own existence; it is a vehicle for "denuding false myths of national purity," a realm outside the ordinary tropes of migration, the false linearity of journeys, the subtexts of "fake purity."

Is there such a thing as true purity? Isn't all purity a performance of a posture evoking something?

Posture is a pose that suits the clothes. We select based on what we plan to feel, perform. Anything on Sunday might turn opera—baroque, roccoco—whatever it takes to appear suitable, depending on the day's construction of what it means to be authentically american or romanian or southern or southwestern or post-soviet etc.

To the extent that identity aims towards certainty - towards the security of belonging - it constructs itself in hope of the unattainable. Jiayong Fan's essay, "How My Mother and I Became Chinese Propaganda", reveals how the use of one's voice, the effort to speak oneself true, is complicated by the uses of others. She describes a "Jiyang Fan" created by Chinese trolls and nationalists who rebuked her American citizenship, "even though her body flows with Chinese blood-- the blood of the descendants of the yellow Emperor.." Fan's crime is that of turning her back on her motherland - of rejecting her primary loyalty by leaving and seeking a new mother.

The entire notion of a traitor is a crime based on impurity and infidelity. The traitor is one who lacks loyalty, maintains multiple allegiances, refuses to choose one side in the stadium or spectacle of nationalisms. But betrayal is also intimate: Fan's mother calls her a "traitor" at fifteen, after reading her diary, discovering that her betrayal involved repudiating her Mother's rage, her fury at living a second-hand life, her exhaustion. "It's reductive to compare a mother with a motherland" - and yet the immigrant mother embodies the motherland, it's customs and ways, it's recipes, it's superstition, it's language, it's folklore, its history, it's great mystery, its promise of safety.

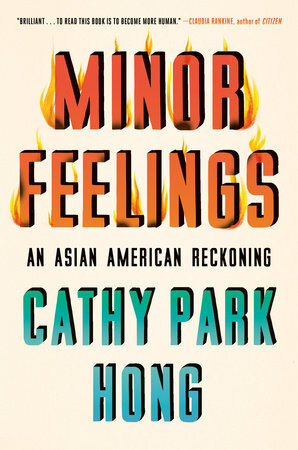

4. Cathy Park Hong’s minor feelings

"Racial self-hatred is seeing yourself the way whites see you...."

- Cathy Park Hong, Minor Feelings

Trauma in the Asian-American diaspora is related both to sites of rupture and sites of erasure. Reading Cathy Park Hong, thinking how Asianness is related to the Eastern desire to be seen as European, to be made Western. The tension between being colonized by Russia or by.... Asian Americans who have assimilated often forsake the connection to the actual nation or country that created them. Asian is default racial marker, per US needs, an americanist construction. This guilt I feel when reaching towards my Romanianness, or mentioning that Russia, too, is a colonizer of nations, and communism swallowed countries and languages. But the ignorance of dominant american ideologies relies on the privilege of using immigrants as agitprop, positioning them against the countries they fled, celebrating each individual as a triumph of assimilationist bootstrap rubrics. O america: where we cannot conceive a trauma that doesn't resemble our own.

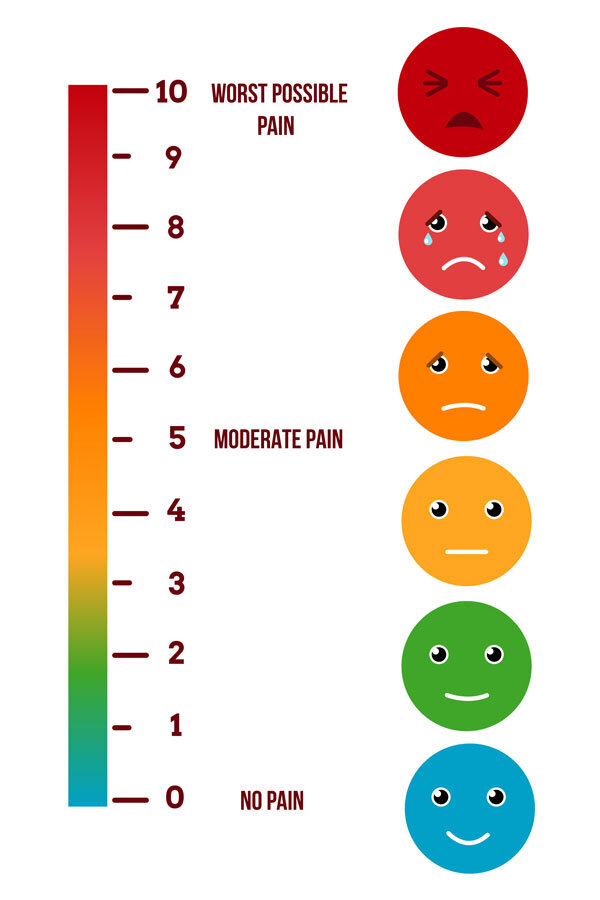

Poet Prageeta Sharma said Americans have no expiration date on race the way they do for grief, and they expect you to get over it. Hong cites then in her discussion of the publishers' low tolerance for ethnic stories that aren't americanzied by trauma. For Hong, to grade looks on "a pain scale" automatically creates a market for pain which quickly evolves into an edifice, a hierarchy, a structure of ascendance. Competing over pain is the americanist in a country where we still cringe if others glimpse our scars.

I keep thinking of the Pixies song and how they tame us, how they cookie us, how the cutting part is shaped as part of the baking process, and then ask us to sell the tool of our submission. To be a beautiful cookie on the empire’s plate.

5. The never-fumble pose of founding fathers

To exonerate Mao, much of the violence was blamed on his wife, Jiang Qing, and three other radicals, who came to be known as the Gang of Four.

- Barbara Demick, "China's Rebel Historians"

While I’m not certain about the totality of Demick’s review, I suspect that many dictatorships have something in common, namely the stake placed on the purity of the founding father, in this case, Mao Zedong, whose Cultural Revolution changed what patriarchy permitted to so many men, starting in 1966 and ending with Mao's death in 1976. About 1.5 million humans died during this event – and this is only negligible if one subscribes to a racism which believes Chinese lives are somehow smaller and less significant or real than other lives, somehow acculturated to this loss.

A tinny leitmotif of founding-father-worship exists across many nations, including the US, where teachers regularly use the words “Declaration of Independence” without irony to describe the founding of a state built from the lives of slaves and erasure of Native tribes and First Peoples. Perhaps one must Jefferson the halls. One must Che the men and blame the women. One must Mao the national landscape. One must put a bullet in Rosa Luxembourg to make space for Stalin. One must subscribe to the power articulated and institutionalized by cults of personality that center men.

Alternately, one may find an Elena Ceausescu to blame for the actions of the Nicolae Ceausescu—a fairly popular take in the Romanian emigre community, where women are easier to demolish, easier to indict for the lack of nurture, the heartache, the messy house, the cold soup, the failed coup.

In "The Art of Being Guilty in the Politics of Resistance: Depoliticizing Trangression”, Boris Buden notes that any firm opposition of us/them must be constructed, since it is hard to create distances under capitalism. Post-colonial world is saturated with diasporas – and post-colonial hybridity is read different ways, by liberals as positive multiculturalism and by others as a force of emancipatory subversion. There is no happy fusion because hybridization "prevents identity's attempt to constitute itself essentially" and be established without contradictions.

The goal is for "transgressive transculturation" to alter the binary nature of cultural power relations by melting the borders, for it is these borderlands between established identities which create the "lines of exclusion and subjugation". But "hybrid resistance must not become a secure space of retreat for those in revolt, an illusionary space of an original innocence".

If you have a car you aren't innocent, I repeat to all friends who have buried the ghosts of what their ancestors did to others in distant lands—if you are alive, your past is haunted by what others have done in your name, which is to say your gas-guzzling lifestyle, your cheap revolutionary t-shirt (a product of capitalist branding), your national self-esteem and exceptionalist billboard.

One must reckon with this presence—in the present—on the page.

Or else find a wife to blame for the whole edifice….

![[Original photo source; words added from my notes]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5aea0d8696e76f6ac6f09e3c/1605725163958-S7MONOB04NMVV73NCE8G/Lipska.jpg)