Anxiety is the epidemic but belonging is the silent hunger.

A photo takes good notes.

See photos above, taken with an iPhone camera.

Jot things down in jpeg.

Assume the ordinary world is asking you to read it.

If you have contact with any supernatural worlds, assume they also wish to be read.

Sensuality lacks a moral compass. A lie can be sweet as stealing apple lollipops, licking them fast, burning down evidence. A wedding can be an example of bright pink peony living too far forward way too fast. A sawmill can be part of hand that shouldn’t be exposed until later. An ambulance siren can be as innocent and reckless as summer kids careening across a street.

It is easy to dehumanize a person in less than a page. When I’m writing difficult characters, I think of something James Baldwin said in an interview: “Perhaps the turning point in one’s life is realizing that to be treated like a victim is not necessarily to become one.” Writing about victimhood does not require a victim. Write your characters the way they would want to be written.

Sometimes you come to that point in a short story where you can’t resist anymore. I remember watching the Alabama Symphony Orchestra perform Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s “Scherazade, Op. 35” from our favorite seats in the choral balcony. The Tale of Prince Calendar. The hands of the harpist like wings loosed in a meadow. Becoming a wave. The kids look at me, querulous, wondering if they can dance, if they can allow themselves to do what the music begs. I say no with my mouth. Firmly. But my body says yes, oh yes you have nothing left to lose.

Czeslaw Milosz: "A flaw: awareness of being a child inside; i.e., a naively emotional creature constantly endangered by the coarse laughter of the grown-ups."

The way adults wear their disenchantment like dresses, the way they lay it down like a wool rug in the center of the room. At some point I imagine it took the tiniest fingers to weave those intricate textures that scratch the cheek.

I lay on the wool rug alone. Like my mother before me. I know we have all come from the dreams of small children. I stretch my arms to make angel imprints and stitch wings to the leaves.

Joyce Carol Oates reflects on the lure of the grotesque, the charm of the vampire as evidence that evil can be as seductive as it is repulsive—that it can render us not just victims but accomplices in its destruction. There is a sense of horror or dread bound up in the grotesque, a sense of perversion in which we can feel how something good begins rotting.

”Extenuating Circumstances”, my favorite short fiction by Oates, is deeply grotesque—and propelled forward by the reader’s dread. One way Oates manages this is by refusing to use question marks at the end of questions. This adds to eeriness—the conclusion and answer have been set in stone by action.

The story is structured as a legal apologia, with first person narrator confessing why she killed her child, and addressing it to the father. Each paragraph proceeds from “Because…” starting with “Because it was a mercy. Because God even in His cruelty will sometimes grant mercy.” It is a perfect piece.

On my desk, a line from Leonard Michaels’ notebooks: “The opposite of mystery is pornography.”

And the opposite of eros is mechanics. Are you writing the optics or the inhabitation? Be thoughtful and deliberate in your choice.

It's always sad when a writer winds up writing mechanistic sex unintentionally.

Almost as sad as finding yourself in the middle of it.

Mona Simpson: “I think day-to-day life changes loves. It can’t stay high, if you know what I mean. Little frictions develop. Did you ever notice the way people married a long time don’t believe each other?”

Oh gold-mine of little frictions…..

Triangulation in poetry is a strategy where writing builds itself on question of winning or losing, attaching certain elements of suspense, moving back and forth between characters without creating connective tissue. The movement--and expectation of movement--is part of the emotional tone. An aspect of what it feels to inhabit that moment.

Lucretius: "Nothing appears as it should in a world where nothing is certain. The only certain thing is the existence of a secret violence that makes everything uncertain."

The writer stays up late palpating the body for scars.

Sometimes poetry and fiction and nonfiction and music blur together and I feel like I’m enacting a harm by trying to separate them. Or to find a space for them on the binary. Maybe honoring genre requires us to offer it a spectrum rather than a check-box.

When the inability to write unsettles me, I sink into something published by Wave Books. Often Mary Ruefle or Renee Gladman.

There’s this wonderful section in Calamities where Gladman remembers the back she took the night before: “…if I was no longer going to write, as I had begin to worry that I wouldn’t, then I should at least write about not writing. And was so struck by the idea that I rose from the tub, dripping, to jot it down, which I was now doing. I was writing down the idea ‘I no longer wish to write’ by writing down that I was writing it down. I wanted a threshold to open that would also be like a question, something that asked me about my living in such a way that I could finally understand it.”

For some reason, this helps me sit down to write.

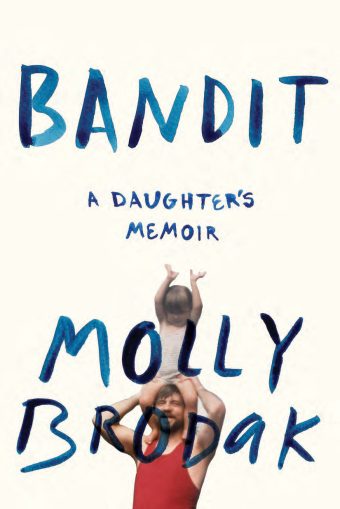

Iris Murdoch: “Every book is the wreck of a perfect idea.” As writers, we work under constant threat of rejection and wreckage. I call it “wreckoning”, that sense that my writing will destroy all that I cherish and hold dear. And then there’s the human worry of failure—the fear of bad reviews, the friends who purchase but never mention the book, the way life goes on as if the book never happened, the fear of polluting intimate relationships by asking too much of one’s readers.

That feeling you’re missing something. What is the outlier? Where does the center not hold? After the short documentary film festival, we split a pitcher of cheap draft, talk about firefighting, Black Panthers, good rap, Talibans, Eastern plans, anything except the albino protagonist. A pitcher shared among Americans of every color still cannot ease the tension of race as we construct it. The box we build a box lacks a choice that acknowledges albinos.

To describe someone as “strange” is the greatest compliment in my arsenal of tiny love-tanks. Michael Martone is strange. I say this although I’ve only spoken to him twice (and very very briefly with kids tugging at my shirt). Martone knows how to estrange the ordinary—a superpower I covet.

Coveting is good.

I covet my neighbor’s wife (and every wife, for that matter, wives in general).

I also covet my the way my neighbor’s wife man-handles idioms.

My heart is dark with the pleasures of covetousness.

Things that drip into the writer’s mind while waiting in the carpool line. Egon Schiele's rendering of human bodies and empty cityspaces, the abandonment of realism in a world where reality is a form of propaganda. His unexpected, early death in the Spanish flu epidemic preceded by the death of his wife and child from same virus, the ravage of Bohemian Vienna but not yet Hitler. The writer lists her appends her influences to include: all interwar periods, all spans of time between one bomb and another, what bourgeois americans damn apart from themselves, conversations in 24-hour gyms, female bodies. She sits on the couch between Audre Lorde and Hannah Arendt with Schiele in her head. And Syria.

I spend most days waiting to write. I wait for the words like a character waits for her lover, the one whose voice carries the story.

Jesus turned water into wine at a wedding in order to please the guests. The writer turns water into wine to show how we are powerless in the face of temptation.

I write with loyalty to the things, places, and people I’ve loved. Not from nostalgia but out of respect to the mammal I was, the girl who loved them. I can love my husband and still write about loving an X because that girl is gone. Her disappearance should not be an excuse for erasure. I can love the girl while acknowledging the tree feels different. I’m talking about the sapling before the thickened trunk, the massive canopy, the curved hips of branches. I can’t discredit the yearning of the sapling while acknowledging myself as the tree. May these branches leave space for all the girls I’ve been, all the compost I’ve yet to be.

Sometimes it helps to follow Walker Percy’s suggestion and play the alien anthropologist to whom every gesture is a mystery and possible code. I park in the lot two streets down the mountain and watch my family move from window to window of supper. Preparations. A man and three kids crowding a bowl. Cozy if you can’t overhear the missing ingredients, the sugar lost to coffee.

In art, the bird’s eye view is one that foreshortens from above. Artist Egon Schiele made powerful use of the bird’s eye view to defamiliarize landscapes and towns. In his paintings and sketches, cities, streets, and trees are empty of human objects and flesh. The viewer is estranged from the view. The use of high, lofty viewpoints, fragmented motifs, simultaneous presentation of non-simultaneous states, depersonalization of motifs, and the effect of empty background deliberately removes us from the real and feel of it.

Sigmund Freud, 1915: "Our own death is indeed, unimaginable, and whenever we make the attempt to imagine it we can perceive that we really survive as spectators."

To survive towards death.

My death has been spectated one thousand ways now, all of them likely, all of them met with astonishment.

The first time you die is as surprising as the multiple others.

Turbulence on an airplane is a terrorist. The profanity of fear, its octane metal in the mouth, I am biting and biting the bullet. Bite down at take-off and then again when we land. I can't believe. I'm alive.

So many poems begin in astonishment at being alive.

But it would be silly to stop and grab my friend by the shoulders and shout “isn’t this unbelievable?”

It would be especially ridiculous to do this as often as the thought overtakes me.

The thing about paper is that always wants to know my astonishment.

Every scene needs the subtext of possible neon. I like to mull Steve Almond's critique of reality TV: It's about the careful construction of two central narratives: false actualization and authentic shame... it reflects our unrequited yearning for the authentic.

Americans are drowning in a cesspool of fake emotion, nearly all of it aimed at getting us to buy junk. — That’s either a great story or a boring sitcom.

More than fifty years ago, the Higgs field emerged as an omnipresent expanse of energy that explains why some theoretically-massless particles have mass. The boson was predicted to appear when a particle interacting with the Higgs field excites it. Since physicists could not directly observe the field itself, they looked to bosons for evidence of the field's existence. Nothing is finished.

Phenomenologically speaking, the swan has yet to dive and its white is soundless. I am fine. Not even wet. My ears ring with crickets and uninvited bullfrog events. A disjunct between two connected places— this grimy lake and the downtown four blocks away. One being the boson to a Higgs field that proves its existence but I am too lazy to discern which.

Again, this lake where most teens in my town get pregnant bears an invisible physical relationship the downtown clinic where they creep behind bodies to secure an abortion. To visit one is to feel potency of the other by implication.

To wake up in the morning, pack lunches, and thank the cosmos for Mary Gaitskill’s “The Agonized Face”.

This is an argument for the value of fascination. For the mundane and extravagant act of attention in shaping what the mind makes of the eye. Georgia O’Keefe was so fascinated by the evening star that she followed it into the wide sunset space in the desert. She said ten watercolors were made from that star. One star in the desert, holding her tight.

After George Sand's death, Ivan Turgenev wrote: “What a brave man she was, and what a good woman.”

There are so many stories in this, though not one leans into Hemingway’s “muscular writing.”

“Pain is not the only thing.” It’s not even the most interesting.

Susan Sontag, in her notebooks, 2/23/1970: “My idolatry: I’ve lusted after goodness. Wanting it here, now, absolutely, increasingly… I suspect now that lusting after the good isn’t what a good person really does.” Schopenhauer listed pain and boredom as the twin evils of life. What is the worst lust? What hunger lies beneath the heroin?

Grace Paley often reuses the same narrator. And begins in medias re. The power of her opening lines is such that it carries us straight through a story, straight into the scene, the kitchen, the room, the action of voices colliding, arguing, explaining. It is said that Paley stitched her stories together inch by inch, paragraph by paragraph, whenever time permitted. She also added scenes to stories that had been previously published, thus changing their tone and meaning. One can’t help feeling that Paley had a certain loyalty to these female characters—a loyalty so profound that she alienated readers or editors rather than the women in her kitchen. Each story is structured by rhythm of thought and conversation.

How fear of death—knowledge of it—cripples life.

A rock is not a pedestal but a possible murder weapon.

All things turn to their endings.

My mother’s fear of dying young and leaving us motherless. Like her mother left her by dying young. As if dying young is lifestyle choice.

The fear of losing family and safe ground—the fear that chased her to America, having nothing left to lose in her mother tongue. And nothing to gain except forgetting—that unique American freedom that sets up apart from history, apart from settled accounts.

At the local level, racial segregation was maintained by white women who wrote letters and lobbied local officials, censored textbooks, hosted essay contests for local schools, policed racial boundaries as administrators, and taught kids racial hierarchies that emphasized white over black as a natural order. No one forced them to do this.

You don’t have to force your characters to do things as long as you allow them to respond in a way appropriate to their socialization.

The alliance of white motherhood and white supremacist politics continues today. Iconic images of white supremacy privilege male images of violence, revenge, legislative power, or dominance. The assumption that women are maternal and progressive is a form of biological essentialism that blinds us to what women did then and what they do not. Think Roseanne, hen mother.

The “gardeners of white supremacy” tended Lost Cause mythologies, cotillions, fear of outsiders and United Nations, sowing the seeds of white supremacy for the future.

Some people will not be able to accept this truth unless they read it under the guise of “fiction.”

You can’t save the world but you write about a woman trying to save the world while destroying it.

Grace Paley, again. Her stories hinge on a pattern of exchange and response that is more spatially-demanding than linear. You don’t have the sense of going anywhere but you feel very alive. The events and changes are situated within a mysterious relational fluidity in which the outcome is hard to predict. What changes is not so much the character as the relational space between characters. The re-negotiations of intimate space after love, children, war, and dinner.

All writing is political. There is no way to write without touching socialization. Even an article about a high school football game is political in that it presumes the existence of human bodies playing by rules that harm them in the hopes of being seen. Or respected. Or given power. Or just loved.

Learn how to tilt tone.

The Oliners interviewed 72 German bystanders to arrive at a better understanding of their reasons for not acting or speaking out against the Holocaust. Most were characterized by “constrictedness, by an eye that perceived most of the world beyond its own boundaries as peripheral. More concerned with themselves and their own needs, they were less conscious of others and less concerned with them.” Only a small minority of bystanders were true ethno-centrists who didn’t like outsiders. Most bystanders were church-going Christians active in their faith communities.

Victoria J. Barnett called indifference “the leitmotif of the literature of the Holocaust.” The most common behavior we see during the Holocaust, whether by perpetrators, terrorized victims, or passive bystanders. Fatalism is its handmaiden.

From Teju Cole’s Open City: “Look, I know this type, she said, these young men who go around as if the world is an offense to them. It is dangerous. For people to feel that they alone have suffered, it is very dangerous…. If you live as long as I do, you will see that there is an endless variety of difficulties in the world… if you’re too loyal to your own suffering, you forget that others suffer too.”

To write from outside the outrage of personal suffering and into the vulnerability.

I can’t envy belonging—I’m too grateful for the perspective nonbelonging imposes on the lonely, left-out mind. To be outside the circles, disinvited, negligible—how else to witness the absurdity of group dynamics, the lies we tell in order to sneak into a stadium?

It would be easier if I could swaddle myself in cynicism or a knowing materialism. But I believe too much in beauty and passion—I’m too riveted by this life.

Humans change the meaning of words each day the sun rises a slightly different color. No liberalism stays fixed, no freedom is not another person’s encroachment. To call myself a “Democrat” is conservative, asserting a static construction of meaning to a category that cannot, by its nature, remain the same. What is my political position? I am firmly anti-totalitarian and anti-authoritarian, and this is grounded in a deep concern for human rights. As technology alters the nature of human rights, I can only commit to what I don’t believe we should tolerate. I can only commit to the “No.”

And what we want from Anne Frank is forgiveness, the cheap grace of hindsight, the blamelessness of looking back. An easy teleology which unites progressives and conservatives in their belief that history will not happen again.

I can’t agree.

I see no telos in life.

And I fight it in my short fiction.

I’m thinking love between brackets. Like it’s 2 am and still taking temperatures from the tongues of little mammals, the offspring of love getting sick, needing nurture. A story that demands foregrounding. Even kids become part of the stage set keeping lovers apart. And yet the memory of the face I fell involve with is edgy, dangerous, blurred as a police sketch. Jets bust open the sound barrier. Rain plinks into a metal plate in the fireplace. Parts of us cannot shut completely. A house with a mouse. And you—trying to find the entryway into our marriage. The way your eyes clench lists fists over me when time passes too fast.

Feminism’s collapse into the master’s tools, the overt militarism and violence, the strong sense of group belonging that makes it a crime not to Other. Not to emphasize the Otherness at the expense of the human. To manipulate fear and prejudice against these others upon which our identity is built. To pose in camos with a weapon of mass destruction. The role of my status as witness against xenophobia is not to claim fraternity with the brown bodies in deportation camps—not to pretend I know how it feels to be a slave or to be trafficked or to be desperate for acceptance. It is to speak not of my minor plights but to pass the mic to brutalized bodies—to show how skin color protects no one in the former Yugoslavia or Africa. The enemy is not solidarity and difference—the enemy is power and violence.

Varlam Shalamov’s Kolyma Stories blurred genre between fiction and memoir by necessity. In telling stories of life in Soviet prison camps, Shalamov switches point-of-view often; and many times, he does this to inhabit the POV of a dying prisoner. To tell the story of that person’s final minutes. There is something unspeakably brutal about death in the taiga, a place so cold that the buried bodies are preserved in permafrost, never rotting into the soil and being absorbed, never composting to serve as nourishment for future life.

The image of those frozen human statues is an ars poetica that carries us through the book, justifying the narrator’s detachment and lack of feeling.

No, it’s not a leitmotif. That’s not what I meant. The frozen bodies are an explanation for why he is writing, a key into Shalamov’s formal choices, and an expiation for the crimes of the survivor.

In 1938, Simone Weil suffered from a series of acute migraines. She began to recite George Herbert’s poem “Love” while sitting in a French chapel, trying to link the pain she was feeling to the passion of Christ. She felt Christ come down and take possession of her. She said it changed her life forever. She knew. But she also refused to be baptized, refused to become one of the chosen lest that position make it harder for her to help others. And so the writer guards her marginality, and the freedom and loneliness it secures. The assurance that she cannot rest easy in the comfort of belonging. She cannot earn a stake in not saying certain things out of fear those things will alienate her from others. She stays alien.

Maybe the urge to stay alien is a religious impulse.

The poets laureate of the Communist empire take their vacations in Florida now. It is wrong, they say, to offer false hope. It is a crime to give the desperate a choice they can’t make in good conscience. Desperation cannot make decisions. All the words we find to sanitize death still give chills when applied to insects. There is no kind extermination.

In search of lost silences. The silence after losing a fishing lure in the creek, knowing you can’t fish anymore but not yet knowing what that means for the rest of the day. How the day will be transformed by loss. The silence on a Greyhound when your seat-mate watches porn on his iPad. The silence of the moment before anesthesia sets in. The silence of a city street at 4:17 am. The silence after bad sex. The silence after good sex. The silence straining across a traditional family dinner. The silence of a monastery. The silence you choose to protect others. The silence on a porch with a close friend when neither felt the need to say anything. When silence was enough.

I don’t know why we think that dying is the time to say those things held deep in the dark. As if the immanence of death is not a continuous presence. I don’t know why we wait to write the revealing thing.

Ben Marcus says fiction has no formula—“you have to solve for x again, every time.”

I think of my kids, raising them, watching them defy the boxes I’ve built to protect them, boxes of purity, in a sense, boxes that preserve them from contamination. Marcus expresses the strongest appreciation for stories that do not parent, fiction that does not provide a box that relieves our anxiety. In a sense, the dread and complexity serve as a comfort, an unhidden gash. Let’s talk blood.

Let’s say I write a story about my mother, a formidable feminist whom I prefer to keep as a talisman of strength and irrepressible will. A story that makes her victorious is a story that ignores how traumatized she must have been to defect from Romania and leave her one-year-old daughter behind not knowing if she would ever see her again. How can I write a story that ignores the PTSD required to leave a one-year-old behind as she ran to the USA, with only a story and two hundred dollars and an equally reckless, desperate spouse? The 50 percent odds. The child she almost lost by never seeing again. The baby in hidden in her belly (my sister). The name she took from her mother who died of breast cancer three months before my birth. The middle name she legally appended to keep her mother close. To bring her here. Tell me what you taste of fear.

It’s important to remember that pathos is integral to the kleptocratic market economy and its literary frenulum. One shouldn’t shy away from the obvious.

A hesitation is not a pause but an attempt to reconsider longing, to revisit hope. In dialogue, a hesitation should be distinct from a pause—should be written with poignance. Deborah Levy says the point of writing is to tell the story of hesitation, or the ways in which fictional characters try to defeat a particular longing or long-held wish. The horrible long spaces between sobs which indicate the deepening of the sob.

The writer does not have the option of keeping their private life to themselves. E. B. White compared essay writing to taking off one’s pants without showing one’s genitals. Margaret Atwood admitted “You need a certain amount of nerve to be a writer, an almost physical nerve, the kind you need to walk a log across a river.” When my partner asked why reading was so terrifying, I told him that reading my own writings is like performing a striptease without the buffer of compartmentalization. With each word, one makes a choice that can held against you, a step in the direction of nakedness and raw vulnerability. As existential philosophers were quick to note, courage does not mean an absence of despair. Courage means an ability to move forward in spite of despair and dread.

Ralph Keyes talks about “that naked feeling”, how writers tend to feel all of the time. “Those who put their words on paper for public consumption live in fear that whoever reads their words will see right through them. At the very least, readers will discover what they themselves have suspected all along: that they’re faking it.”

The risk of candor is real. A candid writer risks being seen for their authentic sincere self and being deemed uninteresting. Isn’t it better to wear a mask? Keyes notes that “authors always feel in danger of being abandoned by loved ones.” And this fear leads to large pockets of silence which swell into regret or a sense of servitude, the feeling that one sacrificed truth to popularity and likableness.

The estrangement of an iceberg, it’s unfamiliar use of space altering the surroundings. A horizon pulls back from icebergs and a sky rises with no intermediary—no lines of compression behind them to mark the in between. I don’t know where death begins and life ends. For a girl who loves borders, this space of death is daunting. In making this map, I sever the ties between beholding a beholden. I think the act of writing, the cartography of bars and landscapes, is a middling guide at best, and sometimes, just this trash you are reading before you return to your own.

While we can describe the experience of realizing that we are wrong, it is impossible to describe any sort of feeling associated with simply being wrong, or with wrongness. When we are wrong, we are mostly oblivious to it. The problem of error-blindness means that error feels normal, and the falsehoods which we invest with belief are not visible. Since it’s impossible to feel wrong when wrongness is imperceptible, we conclude that we are right. And since our brains don’t file away a category of mistakes we made, each mistake emerges as a surprise and a shock, something we can’t take as evidence or use to create a rule about our tendency to make mistakes. In essence, each mistake is an anomaly.

Roger Rosenblatt observes that we “exist in the fold of human failing.” And the hunger for power that creates tension in a relationship. The tension engine.

We tend to overwrite rejected beliefs and build amnesia for our mistakes, which makes it difficult to a accept wrongness as part of the way in which our minds work, as part of the way we arrive at knowledge. Nothing happens easily. This is an argument for slow fiction.

We are torn between wisdom and schedules in which a woman’s plan for life leaves little flexibility or margin for error. Maturity, the ability to defer gratification and wait for an outcome, seems close to the planning and preparation of digital dating but the risk is absent. The absolute folly of love is set aside for the predictability of good companionship. By rendering each need instantaneous, the internet makes delayed gratification look too much like weakness. As if writing is always a doormat and never a glimpse of the sky.

The smocked bodies or the the bodice I failed to smock, the unburdened collar, the frayed meter of the footstep. My chronic restlessness and sinking posture. A tone but not a story.

I’m a fan of indirect dialogue because, in my experience, humans are rarely clear or eloquent about what they want but the fragile banality of actual conversation feels stilted or bumpy or faked on the page. It’s hard to write a real conversation without losing the reader.

The first line begins with what someone wants at the end, and action is how we get there. Usually the fixed desire is modified by movement across time and space, an accumulation of events and altering scenarios. You are not the same person at the end of a good story. At least, that’s the “good fiction” conceit.

But what if you are the same person?

What if you just agree to say different things and wear red jeans to church?

Maybe characters aren’t that different from human beings. Maybe they look like they’ve changed for the purpose of a special moment or a Thanksgiving dinner but they’re still Trump voters inside.

Broken beliefs, busted ideologies. A landscape of fallen statues and broken beliefs. That's how I see post-Soviet Russia--a space in which no ideologies stayed inspiring or possible.

Or maybe a workshop that promises too much?

A workshop that offers the solution to all your writing problems?

There’s something feeble about writing mental health challenges in a way that defines a character. Mental health can only describe us, not define us. Only for a moment and among a cornucopia of other traits and embodiments.

I know it's wrong to put a moral in the story... but is it wrong to twist the story's wrist until she cries "Moral!"?

In ongoing partnerships (as opposed to new relationships), sexual consent often hinges on interpreting emotional tone correctly. (Note: I admire those for whom the case is always a yes/no discussion, but I also acknowledge that some of us start to use other forms of language after years of yes/no together and I think nonverbal communication continues to play an important role for many decent mammals.)

After much disclaiming, I don’t know why consent leads me into thoughts about authenticity and appropriation, but emotional tone is somewhere in that fog. It’s hard for me to write from the perspective of a war veteran because that lack of experience makes my voice too brittle and artificial to carry the heavy parts. Maybe the only emotions I can authentically bring to the table are those I’ve experienced. This isn’t rocket science, but it feels like chaos theory when you’re desperate to write from the place of people you care about. Even though you can’t. Even though it may be best to sit down and think.

As writers, we can't speak for others if this involves replacing or erasing their voice. We can, however, speak with others and in dialogue with ourselves and social institutions--we can show support or affinity by honoring the distance between the witnessing voice and the embodied one.

Tone should reflect (and respect) the limits of engagement. Enter reticence.

I think reticence adds fuel to uncertainty, and uncertainty keeps the reader from getting too comfortable and missing the good parts.