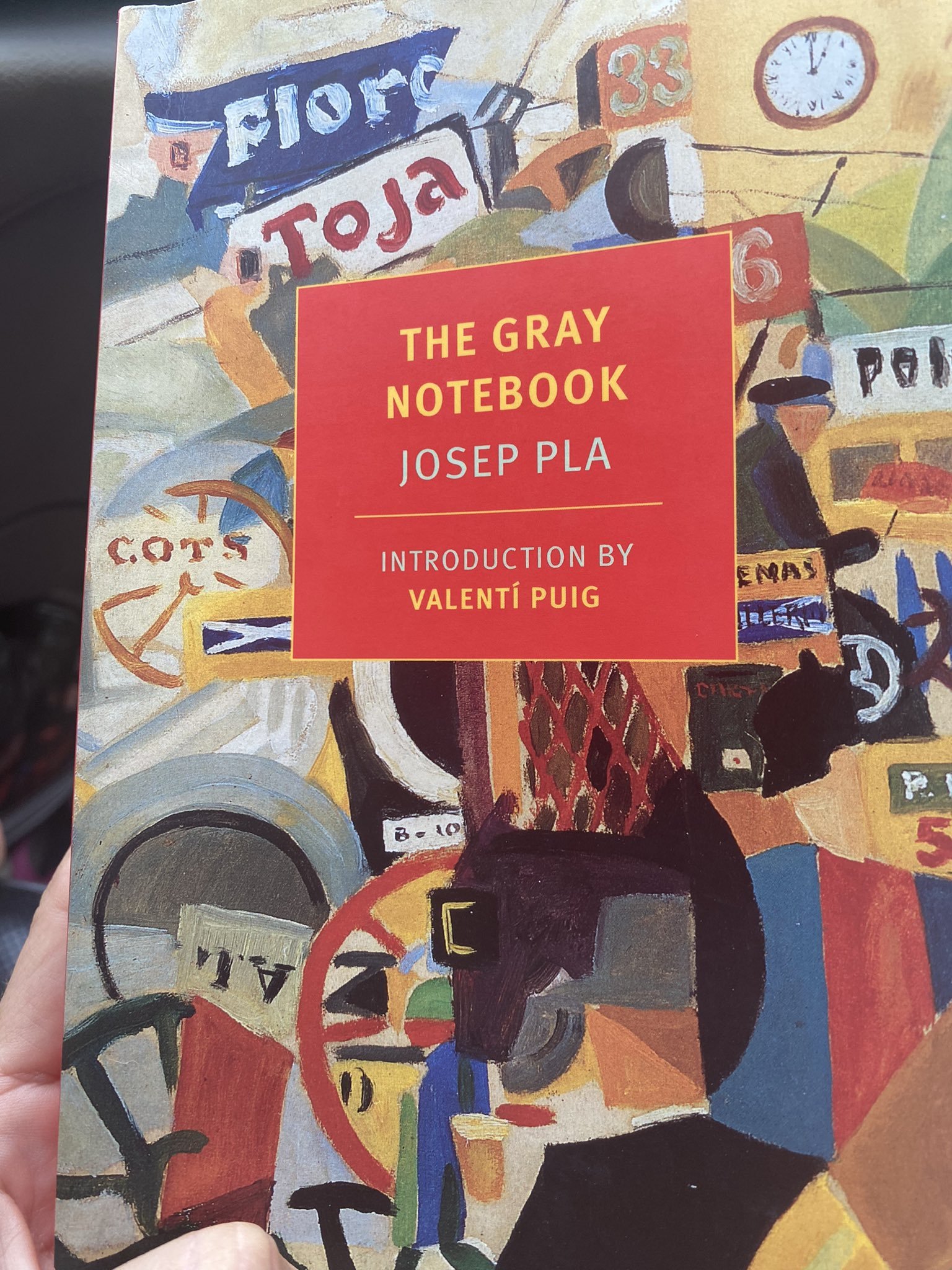

I sit with The Gray Notebook by Josep Pla, in a new translation from the Catalan by Peter Bus, in my lap—-and the fetid heat of the beach in lower Alabama. Not even a breeze lifts the sweat from my neck.

Although two of Pla’s brothers were anarchists, Pla watches most of the social conflicts from the sidelines, electing to write and observe rather than act. Eventually, after maligning his own bourgeois origins, Pla becomes the defender of bourgeois individualism and order, a shift that makes him ideal for understanding the mental landscape of early neoliberalism.

Puig, who introduces Pla’s notebooks, has sketched the author in an “interview in imaginary time but with textual answers” from Pla’s Coses vistes (Things Seen) and Coses dites (Things Said). “Achieving respectability is the ideal of the bourgeoisie,” Pla said, acknowledging the relationship between capitalism and middle-class status-hunger. “Capitalism is anarchic, as I believe, but humanly speaking it is effective and productive,” he added, because “socialism is adequate but inefficient.”

An excerpt from Puig’s interview with Pla on Catalonia:

In The Gray Notebook, one is offered the adolescent and youthful Pla, the student and surly teenager who complains constantly about his parents’ stifled behavior and derides his mother’s obsession with cleaning the house. This young Pla watches the first world war in Europe simmer along the sidelines of the tiny Catalan village of his birth, where superstition reigns and bravado is the order of cafe conversation.

Much as Pla derides these superstitions, he eventually comes to adopt the view of the local fishermen, namely, that weather determines character, illness, behavior, and disposition. One can see this view edging into his notebooks as he studied in Barcelona, on January 25, 1919, when he links the wind to a migraine:

His description of the migraine and its relation to teeth sets my own on edge, and I can feel the cusp of yesterday’s migraine trying to find its way back into head.

Pla postulates that meterology might be the “theology of the future.” And he lays out various opinions on literary style—-he loves realism, condescends to romanticism, finds inspiration in Nietzsche, and laments the emotional pageantry of Spanish literati. I love Valerie Miles’ description of Pla’s persnicketty “stylistic bylaws”:

Use natural words to describe the object. Unearth the adjectif juste like the pig who smells a truffle.

And Pla had a peculiar way of hunting these elusive adjectives. He literally smoked them out. As he worked on a sentence, he would take out his pouch of local tobacco, or “caldo,” as he called it, and begin the ritual of rolling a cigarette as he wrote and thought. With each movement of his fingers, the touch of the rice paper and the tobacco, the rhythm of the rolling and licking and finally puffing, he would draw the adjective out of its hiding place and capture the natural cadence of a sentence. “The only place you’ll find an adjective is in the pauses that result from the elaboration of a cigarette and its intermittent combustion,” he said.

“The family is an institution that exists,” Pla wrote. “It is a mysterious, sacred, run down accoutrement”—-an auspicious treasure of decadence and social obscenity. He mines it as it climbs back inside it, looking for seams.

Pla returns to his roots, in a sense, by celebrating the very traits he deplored in the Catalonia village, including the Catalonian causiticity. “Causticity is used above all against any form of facility —of execution,” he wrote later:

It annoys, it aggravates. What exasperates him most about others is what they do. Others are always imbeciles, but the most imbecilic are those who do things.

Like many sentimentophobes, Pla spends an extraordinary amount of time describing the landscape, the weather, the snails along a cobblestone path:

Sometimes, at night, especially in the very early morn, I wake up in bed, fascinated by the darkness, and I approach the fireplace, with its dying embers. I start writing. Nothing. In absolute silence. Sometimes I hear, in the distance, far off, a dog’s broken bark. I like to look though the window, at the darkness that remains and the very first light, so pale, pinks and yellows enjoin the day.

And what could be more romantic, really, than the pinkening light rupturing over “a dog’s broken bark”?