A few notes and excerpts from Hannah Arendt’s The Jewish Writings.

Hannah Arendt maintained an important distinction between ideology and politics. "An ideology differs from a single [political] opinion in that it claims to possess either the key to history, or the solution for all the 'riddles of the universe,' or the intimate knowledge of the hidden universal laws which are supposed to rule nature and man,” as she wrote in The Origins of Totalitarianism.

Ideology’s rigid focus on certainty in relation to itself makes it ideal for setting up moral codes and purity ethics used to determine who is acceptable and who is not. By foregrounding the performance of certain actions to evidence alignment with ideology, ideological thinking lends itself well to religious fundamentalism, cults, secular authoritarian groups, militaristism, etc. For Arendt, a thinking relationship to knowledge is one of continuous learning and discussion and disagreement. Conflict is central to learning. She often refers to the mindset that characterizes a free polity as “common sense,” which she takes to be constituted by opinion, doubt, and cultural belief. Since her terminology is awkward, I added a prefatory note to the following excerpts from her book, The Jewish Writings, which was published posthumously and never intended as book for publication by the author, herself.

“The real goal of the Jews in Palestine is the building up of a Jewish homeland. This goal must never be sacrificed to the pseudo-sovereignty of a Jewish state.”

- Hannah Arendt

March 6, 1942.

In a letter to the editor of Auflau, Arendt attempted to shed light on “who” the Committee for a Jewish Army was representing. Her ongoing concern that Revisionist Zionism was gaining ground due to the formidable ignorance of the American diaspora appealed to reason and invested in exposure as a means of persuading the public to think:

March 27, 1942.

Arendt published her first biweekly column for the "Jewish World" insert included in the Auflau. In it, she remarks upon the strange Americanization of Zionism. There is dread in her voice:

And while all of Christian humanity has appropriated our history for itself, reclaiming our heroes as humanity's heroes, there is paradoxically a growing number of those who believe they must replace Moses and David with Washington or Napoleon. Ultimately this attempt to forget our own past and to find youth again at the expense of strangers will fail—simply because Washington's and Napoleon's heroes were named Moses and David.

The history of humanity is not a hotel where someone can rent a room whenever it suits him; nor is it a vehicle which we board or get out of at ran- dom. Our past will be for us a burden beneath which we can only collapse for as long as we refuse to understand the present and fight for a better future. Only then-but from that moment on-will the burden become a blessing, that is, a weapon in the battle for freedom.

April 24, 1942.

Arendt turned her attention to the promise that “all Israel will take care of Israel” as it was being promoted to smooth over differences between the diaspora and the Revisionist Zionists:

The world in which we live is full of sorcery, magic, and ordinary hocus- pocus. Rising like irregular boulders out of the chaos of ancient and hyper-modern superstitions—-brewed by despair and spread like advertising around the world by machine guns—are yesterday's truths, almost sunk in the mire. And a few of those truths have also been included in sorcery's great book of despair disguised as science. Except that they have been able to convince the masses in direct proportion to their loss of political effectiveness.

May 8, 1942.

Arendt looks closely at Hitler’s rhetoric and how it casts a certain people as the enemy of the state. What she calls “the devil’s rhetoric” is highly effective, and she concludes by noting that one must call a spade a spade, namely, it is not useful to pretend Hitler isn’t seeking a genocide of Jews:

The idea of a fundamental, natural inequality of peoples, which is the form that injustice has taken in our time, can only be defeated by the idea of an original and inalienable equality among all who bear a human countenance. Only a justice that creates just relationships can vie with an injustice that creates unjust relationships. And since—for various reasons, all of which one may indeed deplore—the idea of injustice has been imputed to and exemplified by the Jewish people, those who must fight for equality and justice have no choice but to lay aside their remarkable skittishness and openly speak the name of the Jewish people in order to grant them their share of justice when they justly demand national freedom and to assure them their equality as an equally valued ally. This is the only sort of propaganda for which the "devil's rhetoric" is no match.

Elsewhere, Arendt refers to the ships, Struma and Patria, which were carrying Jewish refugees fleeing toward Palestine in 1940. Both ships were refused entry to ports by the British. On its return, the Struma sunk after being struck by a mine. Meanwhile, the Patria blew up in the harbor before it was able to take its passengers, on British orders, from an internment camp at Atlit (near Haifa) to one on the island of Mauritius. The problem of refugees and stateless persons continued to drive Arendt’s thinking on political forms of belonging and security.

June 19, 1942.

Arendt’s column begins to include a parenthetical address in the upper-left corner. “(This Means You)”: the speaker insisting that the average reader is directly implicated by the facts, the column, and the current events. It’s an interesting formal gesture— a gesture that brought to mind the war propaganda posters of Uncle Sam pointing at the audience and expressing a similar command.

Again, the clarity of the situation: Arendt took Goebbels at his word while American intellectuals argued over semantics.

September 3, 1943.

Arendt wrote a letter to the editors of Aufbau titled “The Real Reasons for Theresienstadt.” The letter begins by disputing the newspaper’s description of Theresienstadt as a ghetto “alibi”. No, Theresienstadt “was among the first camps”, Arendt points out, adding that, since 1940, she has been “been very closely following all deportations and measures taken in the camps and believe that a consistent political agenda lies behind them all, despite occasional local variations.” She then lists several examples of strategies and patterns she has observed in relation to the concentration camps. I quote two of the five below:

December 17, 1943 & December 31, 1943.

Arendt publishes two columns looking at the future of an Israeli-Palestinian state. She expresses concern over how politics is driving the process:

The attempt to solve national conflicts by first creating sovereign states, and then guaranteeing minority rights within state structures made up of various nationalities, has suffered such a spectacular defeat in recent times that one would expect no one would even presume to think of following that path again.

We need only recall postwar history in most of the nations of Eastern and Central Europe, for the failure to grant minorities the justice due them was surpassed only by the fact that these minorities enjoyed, at least theoretically, the most splendid legal protection.

Then Arendt adds a point she will make again repeatedly— a point that follows from her conviction that seeking a Jewish state will come at the cost of creating a Jewish homeland—namely, “There is no reason to hope that the national problem, which is what we are dealing with in Palestine, can be solved in terms of national politics, and it makes no difference whether one seeks that solution in a small sovereign Jewish state or in a huge Arab empire.”

She continues:

The truth is, to speak in sweeping generalities, that Palestine can be saved as the national homeland of Jews only if (like other small countries and nationalities) it is integrated into a federation. Federative arrangements hold out good chances for the future because they promise the greatest chance for success in solving national conflicts and can thus be the basis for a political life that offers peoples the possibility of reorganizing themselves politically. Precisely because of the strong appeal that this new idea exerts on the hopes and wishes of many European nations, it has become rather fashionable to use the term "federation" for almost any combination of nation-states- from the old alliances to the new systems of national blocs that are now being called regional federations. But whether one plans nation-states as isolated structures or in some combination with other states, the conflict between majority and minority, such as we have in Palestine, lives on.

And as with this conflict, so too with the old alternative between minority rights (as in the proposal of the American Jewish Conference) and the slogan of "population transfers" (as suggested by Revisionists), though the latter will never work without fascist organizations.

December 4, 1948.

There is much to gleaned from the open letter to the New York Times drafted by Arendt and co-signed by Albert Einstein, Sidney Hook, and Seymour Melman, among others. In the PDF attached at the link, one can read the alarm over the US government and American Jewish institutions embracing Menachim Begin in 1948.

1950.

In 1948, Judah L. Magnes, the late president of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, suggested that Hannah Arendt write this paper, based on their conversations and dicussions. From the end of the First World War to the day of his death in October 1948, Magnes was seen some as most dedicated Jewish spokesman for Arab-Jewish understanding in Palestine.

Arendt dedicated “Peace or Armistice in the Near East?” to Magnes’ memory. It was published in 1950. And it begins with a simple claim:

Peace in the Near East is essential to the state of Israel, to the Arab people, and to the Western world. Peace, as distinguished from an armistice, cannot be imposed from the outside; it can only be the result of negotiations, of mutual compromise and eventual agreement between Jews and Arabs.

It is a lengthy essay that responds to the increased hostilities and militarization of Israel. Magnes’ influence is palpable, and one can hear him nodding, for example, when Arendt questions the Spartan mythos being cultivated by politicians:

A mere armistice would force the new Israeli state to organize the whole people for permanent potential mobilization; the permanent threat of armed intervention would necessarily influence the direction of all economic and social developments and possibly end in a military dictatorship. The cultural and political sterility of small, thoroughly militarized nations has been sufficiently demonstrated in history. The examples of Sparta and similar experiments are not likely to frighten a generation of European Jews who are trying to wipe out the humiliation of Hitler's slaughterhouses with the newly won dignity of battle and the triumph of victory. . .

Excessive expenditures on armaments and mobilization would not only mean the stifling of the young Jewish economy and the end of the country's social experiments, but lead to an increasingdependence of the whole population upon financial and other support from American Jewry.

Her comments on diplomacy are critical and obvious and worthy of repetition, particularly at a time when political leaders have invested so deeply in the myth of redemptive violence that Netanyahu’s attempts to raze Gaza to the ground are being igored by career diplomats, whose interest in their own careers keeps them from asking difficult questions. What is a “good peace”?

More ominously, Arendt surveys the changing political opinion among the diaspora:

The majority of the Jewish people feel that the happenings of the last years have a closer relation to the destruc- tion of the Temple in A.D. 70 and the messianic yearnings of two thousand years of dispersion, than to the United Nations' decision of 1947, the Balfour Declaration of 1917, or even the fifty years of pioneering in Palestine. Jewish victories are not judged in the light of present realities in the Near East but in the light of a very distant past; the present war fills every Jew with "such sat- isfaction as we have not had for centuries, perhaps not since the days of the Maccabees" (Ben-Gurion).

[….]

The Jews went into battle against the British occupation troops and the Arab armies with the "spirit of Masadah," inspired by the slogan "or else we shall go down," determined to refuse all compromise even at the price of national suicide. Today the Israeli govern- ment speaks of accomplished facts, of Might is Right, of military necessities, of the law of conquest, whereas two years ago, the same people in the Jewish Agency spoke of justice and the desperate needs of the Jewish people. Palestinian Jewry bet on one card—and won.

The Jews, with the exception of the Revisionists, for many years refused to talk about their ultimate goals, partly because they knew only too well the uncompromising attitude of the Arabs and partly because they had unlimited confidence in British protection. The Biltmore Program of 1942 for the first time formulated Jewish political aims officially—a unitary Jewish state in Palestine with the provision of certain minority rights for Palestinian Arabs who then still formed the majority of the Palestinian population. At the same time, the transfer of Palestinian Arabs to neighboring countries was contemplated and openly discussed in the Zionist movement.

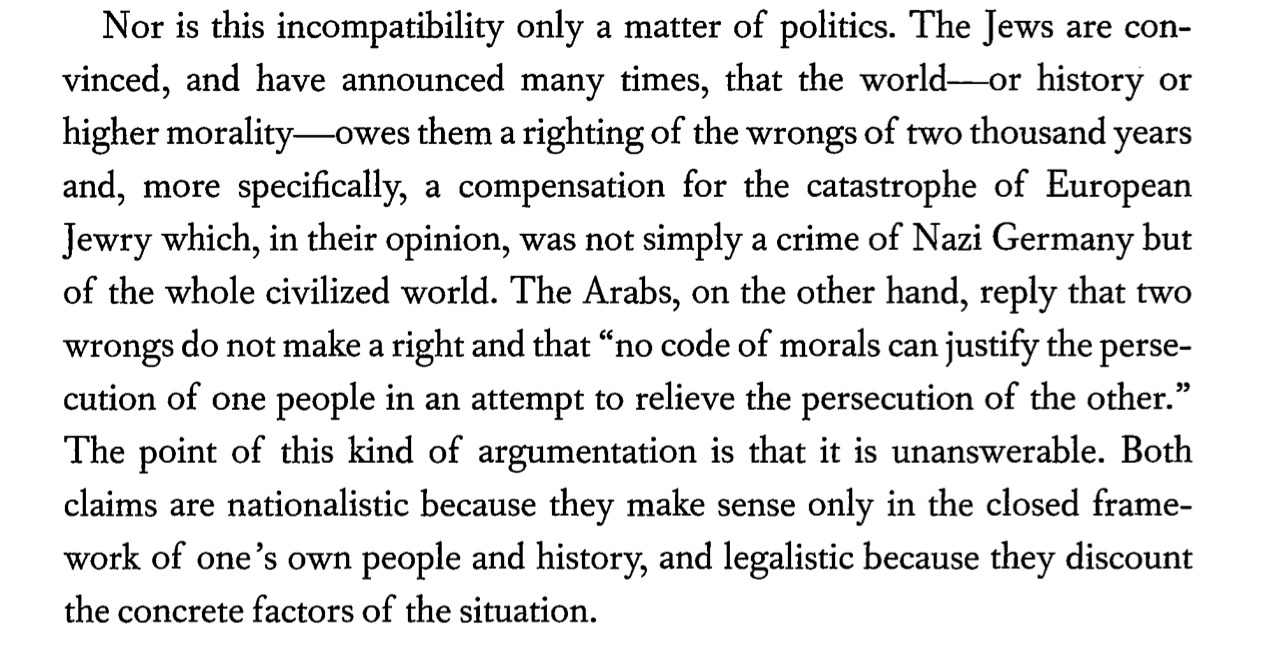

Arendt turns towards these mutual claims in order to remind readers that political leaders have failed completely in offering livable solutions for the future, and this failure is based on the refusal to heed “the concrete facts” on the ground:

Both want power. And both want power as defined by the imperial. Arendt’s thoughtfulness isn’t so much in her conclusions as in her insistence on explaining “the Jewish and Arab failure to visualize a close neighbor as a concrete human being.” Against the Jewish economic miracle, Arendt poses the questions of Arab labor:

It was, however, no accident that Zionist officials allowed this economic trend to take its course and that none of them ever made, in Judah L. Magnes's words, Jewish-Arab cooperation "the chief objective of major pol- icy." Zionist ideology, which after all is at least thirty years older than the Balfour Declaration, started not from a consideration of the realities in Palestine but from the problem of Jewish homelessness. The thought that "the people without a country needed a country without a people" so occu- pied the minds of the Zionist leaders that they simply overlooked the native population. The Arab problem was always "the veiled issue of Zionist poli- tics" (as Isaac Epstein called it as long ago as 1907), long before economic problems in Palestine forced Zionist leadership into an even more effective neglect.

The temptation to neglect the Arab problem was great indeed. It was no small matter, after all, to settle an urban population in a poor, desertlike country, to educate thousands of young potential tradesmen and intellectuals to the arduous life and ideas of pioneerdom. Arab labor was dangerous because it was cheap; there was the constant temptation for Jewish capital to employ Arabs instead of the more expensive and more rights-conscious Jewish workers. How easily could the whole Zionist venture have degenerated in those crucial years into a white man's colonial enterprise at the expense of, and based upon, the work of natives. Jewish class struggle in Palestine was for the most part a fight against Arab workers. To be anticapitalist in Palestine almost always meant to be practically anti-Arab.

The crude nationalist demand of "a country without a people" seemed so indisputably right in the light of practical experience that even the most idealistic elements in the Jewish labor movements let themselves be tempted first into forgetfulness and neglect, and then into narrow and inconsiderate nationalistic attitudes.

[…]

What they overlooked was that Arabs were human beings like themselves and that it might be dangerous not to expect them to act and react in much the same way as Jews; in other words, that because of the presence of the Jews in the country, the Bedouins were likely to want even more urgently land to settle on (a revival of the "inherent tendency in nomad society to desert the weariness and hopelessness of pastoral occupations for the superior comforts of agriculture"-H. St. J. B. Philby), the fellahin to feel for the first time the need for machines with which one obtained better products with less toil, and the urban population to strive for a standard of living which they had hardly known before the arrival of the Jews.

The contempt with which Israeli media speaks of Palestinians at present, particularly those born in Gaza, exists precisely because this history of demolishing Palestinian labor and traditions has created such a crevasse of exploitation that no Palestinian can work in Israel without living in the divided consciousness.

The dream of a homeland was not unitary—-it was not the singular thing articulated by Netanyahu and extremists. From the beginning, the dream, itself, was contested and varied.

Quietly, Arendt expresses her personal sympathy for Hashomer Haza’ir’s binational entity:

“Only one voice eventually was raised in protest to Israel's handling of the Arab refugee question, the voice of Dr. Magnes, who wrote a letter to the editor of Commentary (October 1948),” Arendt writes, before quoting the letter as follows:

It seems to me that any attempt to meet so vast a human situation ex- cept from the humane, the moral point of view will lead us into a morass.... If the Palestine Arabs left their homesteads "voluntarily" under the impact of Arab propaganda and in a veritable panic, one may not forget that the most potent argument in this propaganda was the fear of a repetition of the Irgun-Stern atrocities at Deir Yassin, where the Jewish authorities were unable or unwilling to prevent the act or punish the guilty. It is unfortunate that the very men who could point to the tragedy of Jewish DP's as the chief argument for mass immigration into Palestine should now be ready, as far as the world knows, to help create an additional category of DP's in the Holy Land.

Of Magnes’ letter to the editor, Arendt writes:

I will add one more thing from this essay, namely, the concluding lines:

National sovereignty, which so long had been the very symbol of free national development, has become the greatest danger to national survival for small nations. In view of the international situation and the geographical location of Palestine, it is not likely that the Jewish and Arab peoples will be exempt from this rule.

1952.

Arendt wrote a eulogy for Judah L. Magnes, whose intellect and ethics she admired. The eulogy closes with a warning about the failure of Jewish leaders and Zionists to heed Magnes’ conciliatory approach:

A people that for two thousand years had made justice the cornerstone of its spiritual and communal existence has become emphatically hostile to all arguments of such a nature, as though these were necessarily the arguments of failure. We all know that this change has come about since Auschwitz, but that is little consolation. The fact is that nobody among the Jewish people could succeed Magnes. This is the measure of his greatness; it is, by the same token, the measure of our failure.

With her review of Leon Poliakoy’s Breviaire de la haine: Le lIIe Reich et les juifs [Breviary of Hate: The Third Reich and the Jews], Arendt made herself unpopular with everyone, really. She extols Poliakoy for “correcting” the record and making important connections:

Mr. Poliakov is the first to understand and stress the close connection between the mass murder of Jews and an earlier experiment of the Nazis, the "mercy" killings during the first year of the war of 7,000 deranged and feebleminded people in Germany. Not only did this precede the mass murder of other peoples; Hitler's order of September I, 1939 (significantly enough, on the very first day of hostilities), to liquidate all "incurably sick persons" in the Third Reich set the stage for everything that followed. It was certainly no accident that this decree was not carried out literally and that none but mental cases were killed; it is also possible that what caused the killings to be suspended after a year and a half was, as Poliakov and others maintain, the protests of the victims' families and of other Germans. Nor is it likely that the fact that the beginning of the mass murder of Jews practically coincided with the termination of the "mercy" killings was due to accident either.

She parries an interesting comparison between Hitler’s view of war as wholesale slaughter and that of pacifists like Randolph Bourne:

Pacifism, under the impact of the new experience of machine-made warfare, became after 1918 the first ideological movement to insist on equating war with sheer slaughter. The Nazi party during the 1920S developed side by side with German pacifism and through conflict with it. In distinction, however, from all purely nationalist propagandists for militarism, the Nazis never questioned the correctness of the pacifist equation; rather, they frankly approved of all forms of murder, and of war as one among them. In their opinion all notions of military honor or chivalry, with their implied respect for certain universal laws of humanity, were so much hypocrisy, and included in that hypocrisy was any conception of war that envisaged the defeat of the enemy without his utter destruction. For the Nazis, as for the pacifists, war was slaughter.

Arendt also makes a claim about “radical evil” that she will later contest. I quote it below in full precisely because it will mark a shift in her metaphysics:

And Arendt concludes by likening Stalin’s gulag to Hitler’s camps—-another statement that will increase her unpopularity in various intellectual circles:

Concentration and extermination camps are the most novel and most significant devices of all totalitarian forms of domination. Reports on the Soviet Russian system, whose "forced labor camps" are extermination camps in disguise, are numerous enough and trustworthy enough to permit comparison with the Nazi system. The differences between the two are real, but not radical; both systems result in the destruction of people selected as "superfluous." The development of this notion of "superfluity" is one of the central calamities of our century, and has produced its most horrible "solu- tion." Research into Nazism, therefore, so frequently minimized today as "mere" history, is indispensable for our understanding of the problems of the present and the immediate future.

September 20, 1963.

Hannah Arendt received a letter from Samuel Grafton with questions about her book on Eichmann. He had intended to conduct an interview for Look that later got shelved. Arendt happily answered anyway. I’ve included a few of her written replies below—the first focusing on problems within the assumptions of mainstream Zionism, the second focusing on the banality of evil:

But the trouble is that European Zionism (as distinguished from views held by American Zionists!) has often thought and said that the evil of antisemitism was necessary for the good of the Jewish people. In the words of a well-known Zionist in a letter to me discussing "the original Zionist argumentation: The antisemites want to get rid of the Jews, the Jewish State wants to receive them, a perfect match." The notion that we can use our enemies for our own salvation has always been to me the"original sin" of Zionism. Add to this what an even more prominent Zionist leader once told me in the tone of stating an innermost belief: "Every goy is an anti-semite," the implication being, "and it is good so, for how else could we get Jews to come to Israel?," and you will understand why I believe that certain elements of the Zionist ideology are very dangerous and should be discarded for the sake of Israel.

…

It is of course true that evil was commonplace in Nazi Germany and that "there were many Eichmanns," as the title of a German book about Eichmann reads. But I did not mean this. I meant that evil is not radical, going to the roots (radix), that it has no depth, and that for this very reason it is so terribly difficult to think about, since thinking, by defiinition, wants to reach the roots. Evil is a surface phenomenon, and instead of being radical, it is merely extreme. We resist evil by not being swept away by the surface of things, by stopping ourselves and beginning to think-thatis, by reaching another dimension than the horizon of everyday life. In other words, the more superficial someone is, the more likely he will be to yield to evil. An indication of such superficiality is the use of cliches, and Eichmann, God knows, was a perfect example. Each time he was tempted to think for himself, he said: Who am I to judge if all around me—that is, the atmosphere in which we unthinkingly live—-think it is right to murder innocent people? Or to put it slightly differently: Each time Eichmann tried to think, he thought immediately of his career, which up to the end was the thing uppermost in his mind.