1

At the height of last year’s summer, as screens flashed various diet regimes, workouts, and GOOPisms to prepare the late capitalist physique for the market known as “swuimsuit season,” Matthew Wills’ essay on Eugen Sandow and the buff-cult of American Jesus gave this mind reprieve from the spectacular images of tiny fascia being flexed to demonstrate personal empowerment.

Eugene Sandow, an immigrant to the US, became a buff boy prototype for the “Muscular Christianity” that birthed American Jesus and YMCA masculinity. The “most visual marker of Muscular Christianity” was that “muscled-up Jesus,” as Wills observes, before providing the historical context:

This theological/philosophical movement originated in Britain and was taken up in the US in the late nineteenth century by evangelical Protestants. The movement stressed self-sacrifice, patriotism, masculinity, physical culture, and sports. Especially team sports. Epitomized by the YMCA and ballyhooed in the cult of the outdoors personified by Teddy Roosevelt, the new gospel of health and virility was a reaction against the perceived emasculation of white American men. Anglo-Saxons were said to be growing flabby in office jobs; being replaced in blue color jobs by non-white immigrants; and suffering, as always, under the yoke of emancipated women.

“Not unlike today, when portrayals of Jesus as a Rambo-like figure, sometimes even complete with AR-15, and the seventy-six-year-old Donald Trump as a buff, thirty-something Jesus-like figure, can be found among the iconography of the Right,” Wills concluded in 2022.

Today is complicated by the cross-fertilization of revolutionary soil by the prominence of the myth of redemptive violence on both the right and the left. Increasingly, it feels as if Samuel P. Huntington’s clash of civilizations has returned to ghost radical movements by positioning the “war” between patriarchal religions as the only future worth imagining.

2

Poetry licenses discomfort and permits uncertainty.

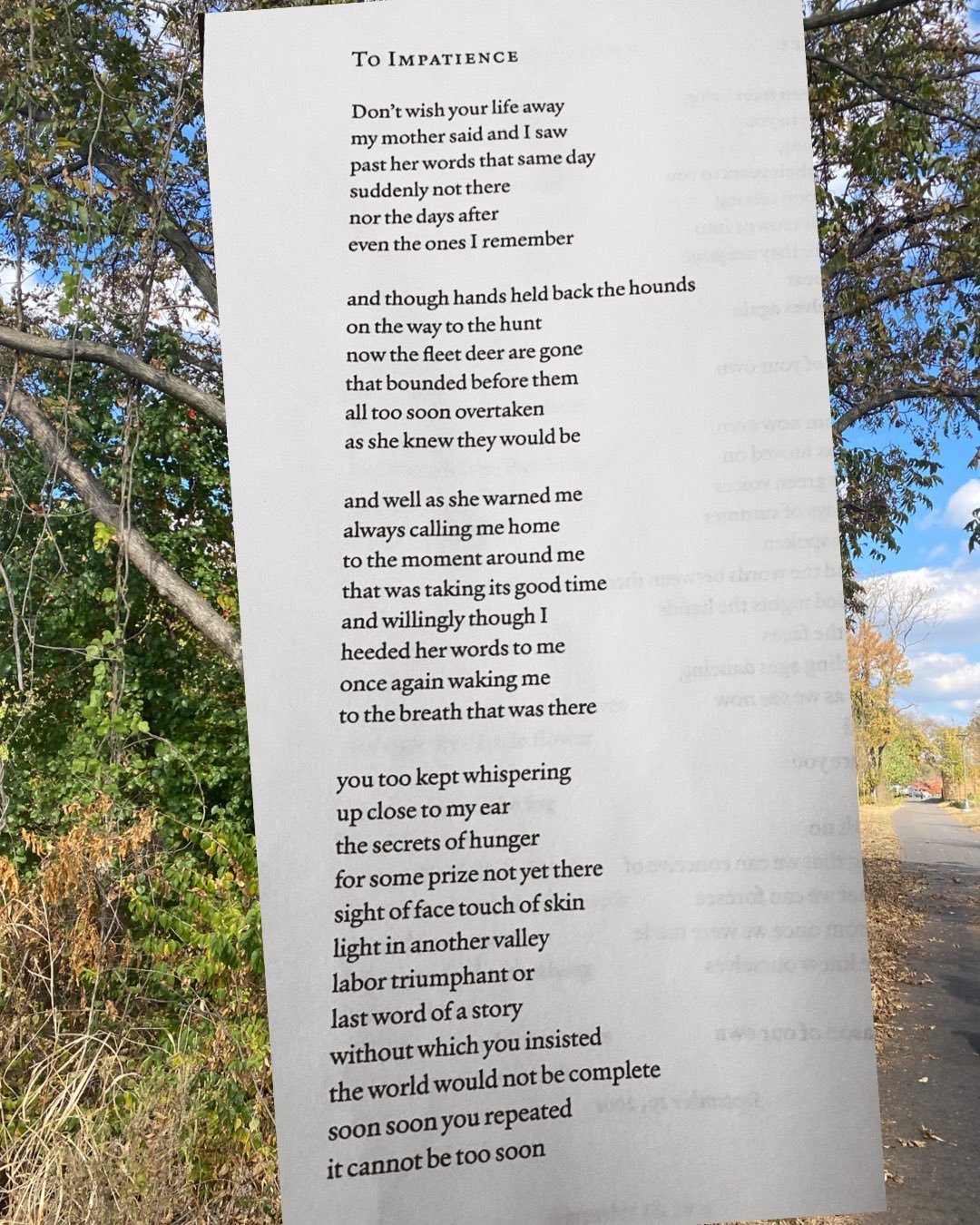

In this vein, I find myself returning to W. S. Merwin’s later poems, particularly his ode to impatience, excerpted in full below, as found in Migrations: New and Selected Poems (Copper Canyon Press):

What Merwin calls “the secrets of hunger” brings to mind a bench in Paris, sketched by Henri Cole in Orphic Paris (published by NYBB in 2018). In an essay, Cole depicts the writer, himself, on a bench along the River Seine, waiting for words to come. An interior parade of events, facts, and personal histories sits alongside the details of strangers passing at varying paces, carrying bags or difficult faces. Cole says: “I await some strange enchantment to make them interesting.”

I await that strange illumination that draws both worlds together in language— “some strange enchantment to make them interesting.” The secrets of hunger implicate the sensation of waiting, of not having the thing one desires or needs. There are different hungers, different longings, different languages, different secrets.

When one writes, the facts are changed: to quote Cole, the facts get “lost forever in representation of them." And "the inadequacy of language" which Cole describes as the poet's task, reminds us that our tool is failure.

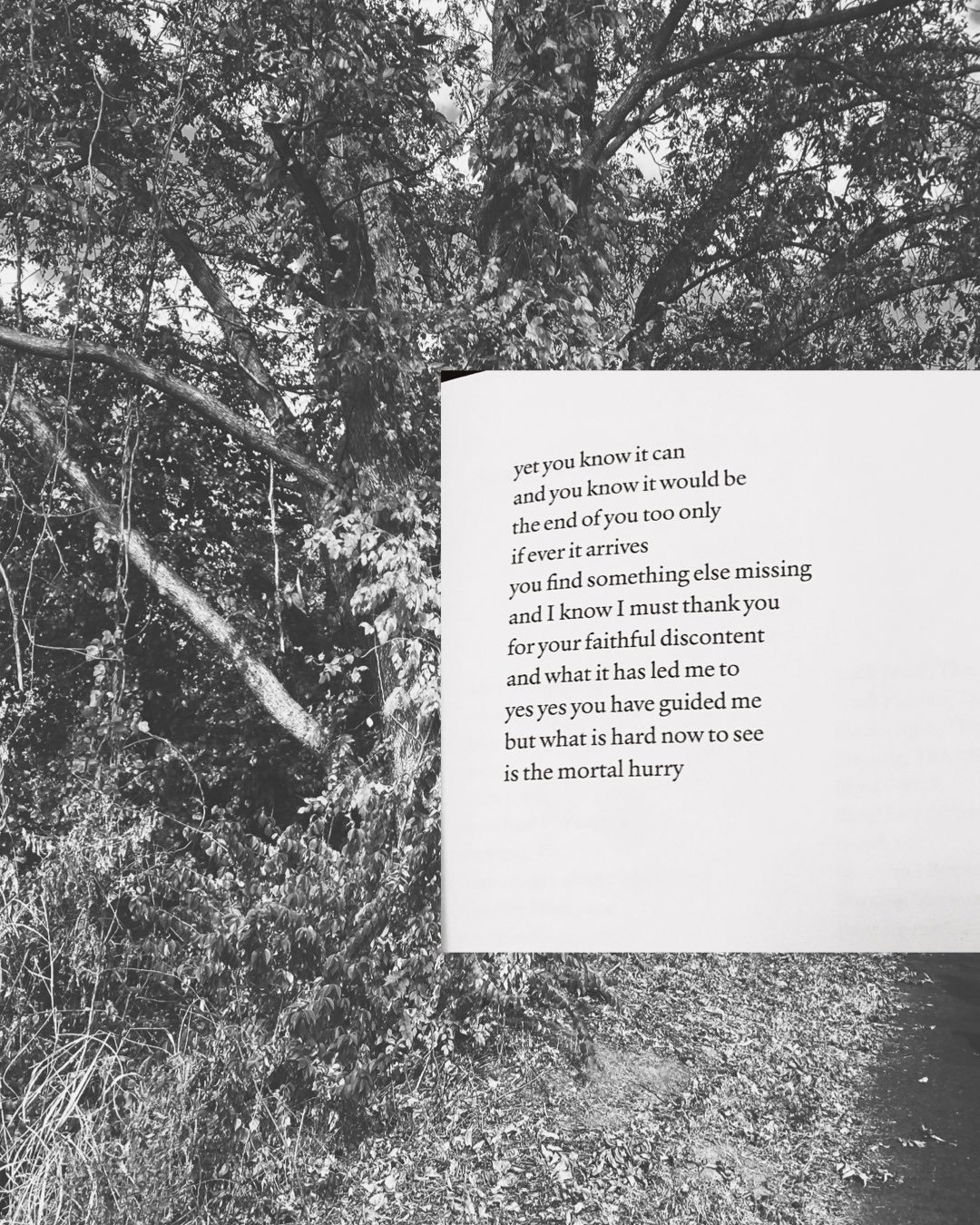

To quote a few lines from Merwin’s final stanza:

and you know it would be

the end of you too only

if it ever arrives

you find something else missing

The "conditional” — the extraordinary “if” of it— means nothing can be finished or completed. So we return to the bench and wait for the thing that was felt to be missing.

3

At its best, poetry “knows” a few things. It knows, for example, that nothing can summarize a human being (least of all in a colonial language like English). And poetry knows it must continue wrestling with its own history, in its urges toward the attention of polemic. The difference between rhetoric and polemic gets skipped, but it matters primarily because rhetorical strategies are part of poetics, part of how we use language expressively.

Polemic gives us the whole thing in a sound-byte. It gives us the glib entirety. A poem that borrows rhetorical strategies from the polemic isn’t a species of rhetoric so much as a poem that cannot keep its promise to the reader.

4

"Ruinous but beautiful," Dan Beachy-Quick wrote of the poem’s speaker, or the events that combine to create the speaking self:

Sometimes I am this series of events that has led up to me. A kind of architecture, ruinous but beautiful (maybe). I mean only I am this self I feel as if I’ve built. Other times, I am this field whose edges I cannot see. Anonymous. No marker that says me.

“No marker that says me”; or, not entirely. No flag that lays claim to more than a language or the country I’d like to be, the homeland that isn’t deeply invested in wars and borders and eviscerations. No single sign is constituitive.

Living in Alabama means being associated with the political decisions and definitions of the MAGA-huffing majority.

There is money in all of this. MAGA scheming and dreaming is tied to market-saturated Christian fundamentalism that rejects scientific expertise for “entrepreneurship” and the art of the sale. The more brutal the sales pitch, the more likely it finds its way to a bumper-sticker or a t-shirt. The children know this.

In Alabama, the children grow up knowing that thinking is less valuable than becoming a sports star or a model— the two gender ideals. I remember internalizing this contempt for my own bookishness. However hurtful this rejection, the poet (as opposed to the mother, citizen, and human in me) acknowledges the fear beneath the guns and big glutes in a culture where the ability to make money or shoot a deer or afford college football tickets depends on networks and communities and access to financial assistance.

The poet knows that the one carrying a gun is the coward. The poet knows the worst sort of power thrives in self-deceit and myths of strength. I remain “of” the South—raised in its schools, a product of its socializations, a beneficiary of white supremacy—and also “outside” it, which is to say, rejected by the good ole boys and gals who don't much trust immigrants or anti-flag writers. There is no way to bridge these gaps; no easy gloss of the distance between the words I was raised to recite and the actualities hidden beneath them.

In this sense, the body translated by borders is a space of contact between the pure and impure: it saddles the binary at the point of friction and signification. Eastern Europe immigrants benefit from Alabama’s white supremacism while also being reminded by the locals that you cannot be one of them. That you were not born here. That your opinions are irrelevant to the future. That your flesh is foreign and not freesia. That you are "lucky" to be given a seat at the table. That your seat depends on learning to kneel.

And maybe I do. Poetry is the pew for me. I kneel to get closer to the thing that elides me.

Again, I quote Beachy-Quick again, to stand, for a moment, in the nimbus of his sincerity:

The poem breaks the poet apart. The basic violence of that which is internal being made external, expressive. What was mine is no longer mine, brought from an inner realm in which doubt is but a temperament into an outer realm where doubt is a fundamental reality. But this violence is generous, even kind. The formal impetus of the poem insists the poem makes of itself a structure of dwelling. What the poem breaks of the self isn’t its nature but its habit, the ease of the limit by which the self is defined. The self awfully liberated from the self, and as in all such births, the first result isn’t wisdom or knowledge or truth, but the basic acts of emerging into a world not wholly known. One gropes. And where one gropes toward is the dwelling the poem has made of itself. To write the poem so as to be within it. Thinking begins in the poem; it cannot begin outside of it.

As for rejection: it is ubiquitous. It is the most basic part of being human. No matter what the culture sells us, there is nothing unique or special in the disappointment. Unlike a pain olympiad, poetry asks us to study rejection closely, to note how it notches our minds and blisters into defenses, to bring the imperfect mess of self to the world as text. It asks less for a representation than an illumination.

5

This close attention to making sense of a single word—here it is “provision”— echoes throughout Merwin’s poetics. His definitions tiptoe away from the definitive and towards the entanglement of meaning, the implication and connotation “in the wall” we cannot see.

The walls we know are not the walls we imagine.

The dead continue building without us.

Provision

All morning with dry instruments

The field repeats the sound

Of rain

From memory

And in the wall

The dead increase their invisible honey

It is August

The flocks are beginning to form

I will take with me the emptiness of my hands

What you do not have you find everywhere