Riveting books curse this insomniac. Thus did I unintentionally burn my way through three midnights this week absorbed in Ross Benjamin’s translation of Franz Kafka’s diaries. I learned that Kafka’s 1908 included an unhappy love affair with a wine tavern waitress named Julianne Szokoll (Hansi). Max Brod said that there was a photo of her standing next to Kafka, and that Kafka said of Hansi "that whole cavalry regiments had ridden over her body."

There are themes— which I will paginate, due to time constraints.

Reproaches

The reproach is thematic to the diaries as well as Kafka’s fiction. On May 18th or 9th of 1910, as Halley’s comet whirs past, Kafka develops his inflamed inventory of reproaches against parents and family. He reproaches his mother and father for his education, and what they failed to teach him; page 7. Both reproach and refutation do him great harm, Kafka tells us on page 8. Addresses the “group pictures “in a fabulous way. Talks about how he introduces them to each other, these family members, these people who have harmed him.

Strangers allow him to detach his mind from the reproaches. Looking out the window quiets “the urge to reproach.” He looks out the window often when standing in a room with his father. Or he begins a scene near a window. Or he uses the movement towards as a window as a transitional device between interior monologues. Or he returns to an image of his father looking out the window. (“Men looking through windows” could be a song on Kafka’s greatest hits.)

After reproaching his family for their failure, Kafka reproaches them for their love, for those who have done him “harm out of love, makes their guilt even greater." For Kafka, family love is almost more dangerous than hate, or more damaging.

Also: "Parents who expect gratitude from their children (there are even those who demand it) are like usurers, they are happy to risk the capital as long as they get the interest."

Epistles

"I have no time to write letters twice," Kafka confessed on November 27, 1912. No time to preserve a copy of his own words—no time for correspondence. Since Kafka’s relationship to the epistolary genre is part of my work-in-progress, take this quote as a large star or a comet. Letters are not different from literature to Kafka—-in fact, many of his letters (particularly those related to Felice Bauer) wind into his fictional characters.

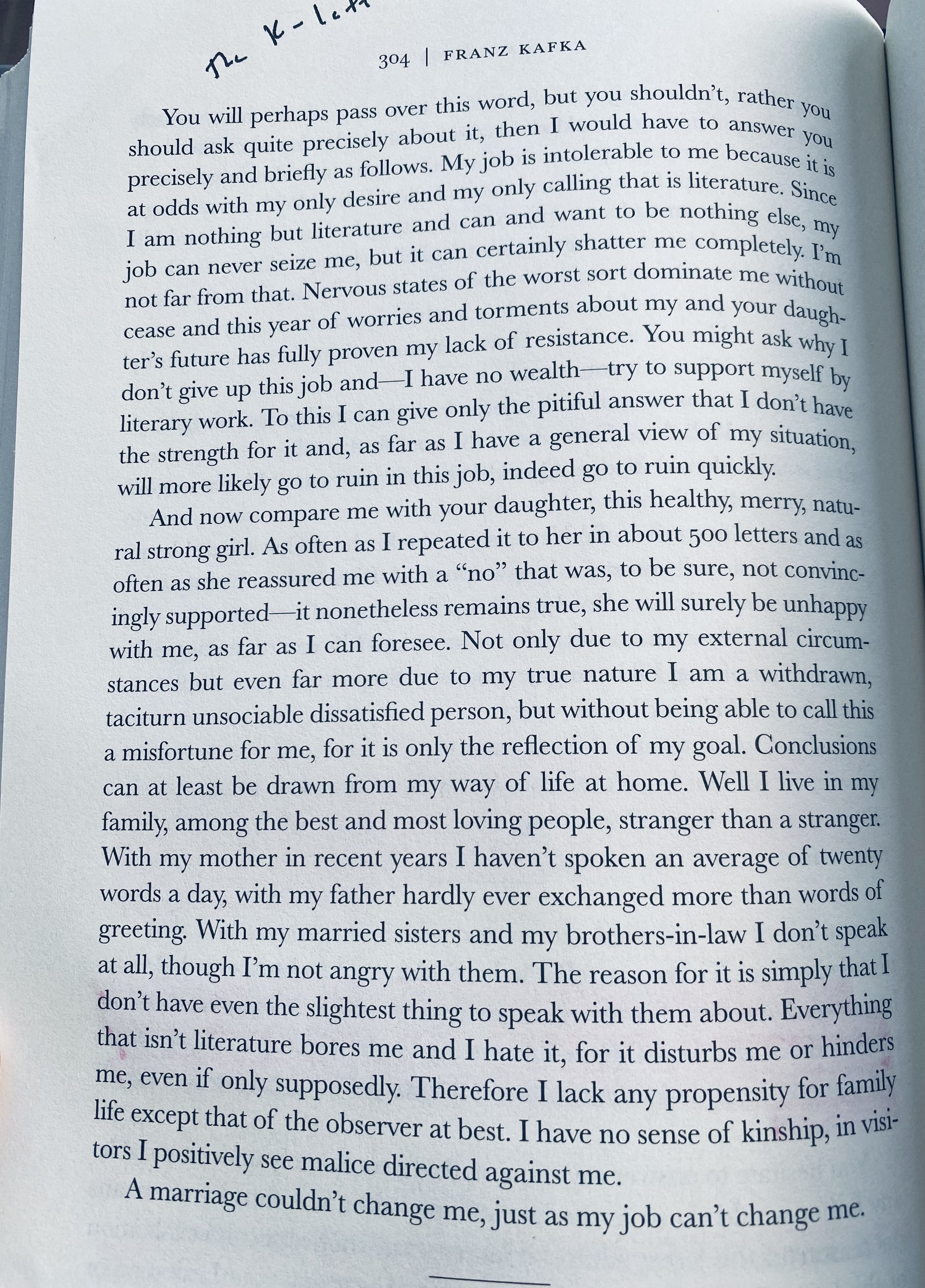

The letter at the top of this post, which Kafka addressed to Felice Bauer’s parents—-after reading Kierkegaard—-breaking off their engagement; the timing is uncanny. The theory of letter malaise excerpted below ties is also critical. Kafka hated being presented with choices, or making large decisions; each decision was approached as a momentous life-changing event.

Restlessness and indecision = anxiety

(13 Sept. 1915): "I don't have to make myself restless. I'm restless enough, but for what purpose…how can a heart, a not entirely healthy heart bear so much dissatisfaction and so much uninterruptedly tugging desire."

Again and again, Kafka defines anxiety as the dread of making a choice, since the interpretations of others will determine the meaning of that choice. The trial is ongoing, and there is no end to it. Dread is simply the awareness of an impending choice, or the space after a decision has been made in which the choice will be interpreted by others. Society writes the book of one’s self daily. Refusing their misinterpretation is why one writes the novel.

Conscientia scrupulosa (scrupulous conscientiousness)— the expression Max Brod used to describe Kafka’s obsessive relationship to moral dimensions, and his inability to “overlook the slightest shadow of injustice that occurred.” In Brod’s view, Kafka is driven by this belief in “a world of Rightness.”

Diary as self in time

Diary as encounter with self in relation to time:

"In the diary one finds proof that, even in conditions that today seem unbearable, one lived, looked around and wrote down observations, that this right hand thus moved as it does today, when the possibility of surveying our condition at that time does make us wiser, but we therefore must recognize all the more the undauntedness of our striving at that time, which in sheer ignorance nonetheless sustained itself."

*

As for Benjamin’s translation, it is the dream of every end-note aficionado to discover the details and traces. Take end-note #577, for example: “The poet, playwright, and composer Abraham Goldfaden founded the first Yiddish theater troupe in Romania in 1876; he is regarded as the founder of the Yiddish theater.” BYOB to the Kafka revival.