Posthumous voice and Machado de Assis

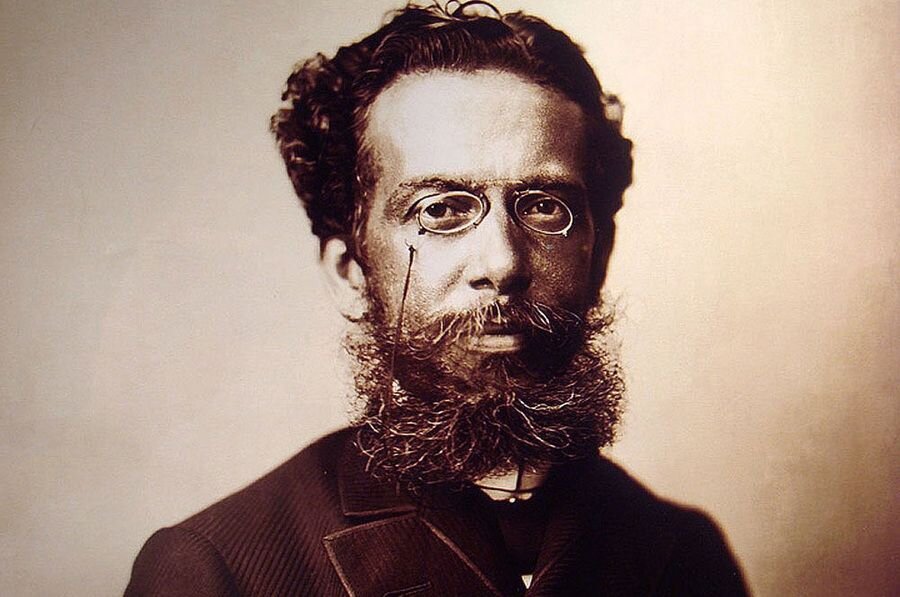

The posthumous voice can be serious, but it can also be light, humorous, critical, as in Machado de Assis' The Posthumous Memoirs of Bras Cubas, first published in Brazil in 1881. For me, what makes Machado delicious in the present is his tonal irreverence, the techniques he mobilizes to establish it, including metafictional strategies, direct reader address, continuous irony, self-referentiality, intertextual intimacy, and typographical experimentation.

As Larry Rohter commented in the #APSTogether meeting for A Public Space:

“Experimenting with margins, punctuation, and typography is common enough today, but Brazilians in 1880 must have found it disconcerting, even revolutionary. Methinks me spies the influence of “Tristram Shandy” in XXVI, with more to come in LV & CXXXIX.”

Machado’s notion of time and temporality, I think, plays into much of this innovative narrative technique, and what it asks of the reader (see unreliable narratives).

Flora Thomson-DeVeaux’s translation

In the 2020 Penguin publication, Dave Eggers provides an introduction to Machado’s wit. The translator notes by Flora Thomson-DeVeaux are fantastic, elusive, rich, and refer back to his newspaper publications at the time (the form in which this book was first serialized). Machado’s "cronicas" ( news columns where he used pseudonyms to reflect on current events) are not held separate here. Thomson-DeVeaux’s translation is the only one to include materials from the earlier serialized editions of the novel, as opposed to the other translations, which translate from the basis of later editions.

I love how Thomson-DeVeaux introduces him as "a ghost with memoiristic ambitions”—and how she translates the open field of the page by beginning each of Machado’s chapters on a new page, as did the author. Since the chapters are short (some only a paragraph), the decision to publish the open field enacts the textual pauses and motion—the shifting temporality and cronica-style insights—in a way that feels closer to the flow of the text as well as the memoir form.

Born in 1839, the mixed-race grandson of slaves, Machado does not ignore ancestors or the past. He leavens it, makes it “of the time” somehow, brings into the bourgeois ordinary in a way that structures what many have called his “unreliable narrator.” The existence of enslaved persons is a continuous backdrop in the text. Thomson-DeVeaux's translation pays close attention to how slavery complicates the narrative, for example, by offering context for the scene in which the formerly-enslaved Prudêncio beats his own enslaved persons in the neighborhood of Valongo; Thomson notes Valongo was the site of Rio de Janeiro's slave market, at one time the largest in the Americas, and so the site of the beating continues the brutality “inflicted in the same place over centuries on literally millions of men, women and children.”

She also notes an anti-nationalist spirit that prefers the "local subject" to the imperial one. Her introduction combines the historical memory of slavery with the yellow fever pandemic of 1850 in Rio, which killed many Europeans rather than Africans – and was read as the revenge of Saint Benedict (who was Black) after white parishioners refused to carry his statue on their shoulders during an 1849 procession through the city.

During the #APSTogether book club meeting, Thomson-DeVeaux spoke a little bit about how love underlies the task of the translator, particularly in William Grossman’s case. While teaching aerospace engineering in Brazil, Grossman fell in love with Machado during his Portuguese language study, and felt compelled to bring him to an American audience back home. He actually self-published his translation of Bras Cubas in Brazil in 1951—and Thomson-DeVeaux noted that there were no existing translations of Machado’s work during his lifetime, apart from a few pirated translations into Spanish.

“A historical note: the Hotel Pharoux, where Bras Cubas spends so much time in his declining years, was a real place. Rio’s first modern hotel, founded in 1816 by a French exile, it closed only in 1959, & during its long zenith was often painted or photographed.” —Larry Rohter

The “status” of death + “the grand idea”

I am interested in the way death, itself, becomes a “status” marker in this status-conscious fictional memoir.

In this first chapter, the narrator describes himself as “a deceased man recently an author, for whom the tomb was another cradle” – and he announces his death as another author might announce his birth—with regalia. We learn of Cubas’ illustrious passing at his country home; we learn his status signifiers, a bachelor of 64 with money to his name, and “eleven friends” at his grave. The narrator renounces tragedy, insisting that he lived a good life - and who are we to doubt it when reading, when realizing the lack of meaning in the status oriented Brazilian culture?

It is clear that Cubas wants to be famous, but there is nothing clear beyond that—and perhaps fame is an empty and meaningless wish which one must pursue in the form of a posthumous memoir. Although the narrator’s official cause of death was pneumonia, he leads us to think what actually killed him was “a grand and useful idea”. And then, in a fascinating fictional move, he tasks the reader with reading his memoir but also serving as a judge. It is the reader who must determine if it was the idea that killed him. This is the new role for a reader.

So what is this grand idea? In “The Plaster,” the narrator describes as the invention of "an anti-hypochondriacal plaster destined to alleviate our melancholy humanity." And then, he does what will become characteristic, namely, he leans over and whispers an aside to the audience:

Now, however, that I am on the other side of life, I can confess it all what drove me most of all was the gratification it would give me to see in newsprint, showcases, pamphlets, on street corners, and finally on medicine boxes, those four words: The Bras Cubas Plaster. Why deny it? I had a weakness for hubbub, banners, pyrotechnics.......... My idea had two faces, like a metal, with one turns toward the public and one toward me. On one side, philanthropy and profit; on the other, a thirst for fame. Let us call it a love of glory.

Cubanos’s love of glory is cultural, socialized—and I’ll return to this—but for now, it’s interesting that Machado keeps letting his narrator indulge in limpid self-critiques which reveal the limits of self-reflexivity.

In "The Fixed Idea," Cubanos warns again the prowess and power of “the fixed idea,” which is what happened to his own idea, or what brought about it’s demise, noting, “My idea, after all it's somersaults, had become a fixed idea.” And then he warns the reader: “God save you, reader, from a fixed idea.” He defines fixed ideas as “what make strong men and madmen; wandering, vague, or shimmering ideas make for Claudius's – in Suetonius’ version, that is.”

My idea was fixed, as fixed as..... nothing comes to mind that is quite so fixed in this world: perhaps the moon, perhaps the pyramids of Egypt, perhaps the late German Diet.

The narrator’s dream includes this plaster which he intends to serve as a solution to melancholy and misery—and he is very clear about wanting acknowledgement and glory in return for his invention. I found myself imagining Bras Cubanos Instagram feed too frequently, or considering how the desire to create a perfect product complicates what ,,,,

Do not laugh at the joint triumph of pharmacy and Puritanism. Who does not know that at the foot of every large, public, prominent flag, there are often a number of other, more modestly proportioned flags, which are hoisted and flutter in the shadow of their larger counterpart, and which quite often survive it?

Machado toys with death in order to tell the story he wants to tell. Death reveals the extent to which literary lineage or inheritance continues in novel form - to have the conversation he wanted, Bras Cubas had to die (or Machado had to kill him), thus setting up a narrative voice that speaks from beyond the grave where all voices are equal. Supposedly. Maybe.

Symbolic objects: The plaster, desire, hippos, clocks, and the worm

Machado makes us of many symbolic, recurring objects, and I will note a few that stood out, starting with the entrepreneurial dream of a special plaster.

In "The Plaster," the narrator describes the sublime idea that hopped into his head while walking, the invention of "an anti-hypochondriacal plaster destined to alleviate our melancholy humanity."

"Now, however, that I am on the other side of life, I can confess it all what drove me most of all was the gratification it would give me to see in newsprint, showcases, pamphlets, on street corners, and finally on medicine boxes, those four words: The Bras Cubas Plaster. Why deny it? I had a weakness for hubbub, banners, pyrotechnics.......... My idea had two faces, like a metal, with one turns toward the public and one toward me. On one side, philanthropy and profit; on the other, a thirst for fame. Let us call it a love of glory."

It feels prescient for theory to be commodified as a sort of entrepreneurship-vessel for the chattering classes, an economic opportunity for leisured libidinals. One can’t help but notice a resemblance between Bras’ Cubas’ aspirations and the contemporary economic muscle of self-help industry experts. We have it all, from Emily Oster’s “evidence-based, statistical parenting” (and other emergent parenting scientists) to the lean-in feminisms of Sheryl Sandberg and Jia Tolentino and straight to the plaster face masks of the Insta-influencer scientists—to be so rich in plaster solutions and yet disoriented, miserable, and clueless. This is the American dream as it plays out in the bourgeoisie classes.

All this content isn’t intellectual, but it’s awfully theoretical. Which brings me back to Cubas, whose relationship to desire and love is closer to theory than practice. Certainly, the desire for desire is there in descriptions of Virgilia. But I’m also fascinated by references to death, religion, salvation—or, as he says in “Trust”, something ”with the religious zeal of a desire seeking to rise from its deathbed.”

The chapter "In Which A Lady Betrays Herself" gives us the lover as a "ruins,” which connotes the statue or the monument after it has fallen into disrepair or misuse:

She was then 54 years old, and she was a ruin, and imposing ruin. Just imagine, reader, that we had loved each other, she and I, many years before, and that one day, having taken ill, I see her appear at my bedroom door.

As the narrator lies in bed, clearly ill, he reflects on the nostalgia of seeing his former lover in her advanced years:

Believe me, remembrance is the lesser evil; let none place their faith in present happiness; there is a picture drop of Cain’s drool in it. Once time has worn on and the rapture has ceased, then, perhaps only then, may one truly take pleasure in what has passed; when given a choice between two illusions, the better is that which may be enjoyed without pain.

For Cubas, pain is the thing to be avoided. Life is the journey towards an afterlife of importance, towards fame and glory. Life is pointed towards death. This is why time, clocks, and pocket watches carry significance.

The chapter, "The Pendulum Clock," lays the sleeplessness after a kiss next to the tick-tock of the clock which makes us aware of time's passing. But I'm interested in how the narrator foreshadows here, or builds significance into the pocket watch:

Some inventions are transformed or fade away; institutions themselves come to grief; but the clock is definitive and everlasting. The last man on earth, as he bids farewell to the cold, sapped sun, will have a watch in his pocket so as to know the exact hour of his death.

Chapter CXXXIX is an ellipsis. Time is not the thing with feathers so much as the endless dots. Notice how ellipses lack causality—they don’t indicate the consequences of an act but the fact that an act may happen. Anything could step into the blank and be gilded by theory’s hindsight.

There’s something fantastic about hindsight and how Machado uses it to undermine respectability and status—something surreal in the aspirational posthumous voice. And the reader is prepared for with “The Delirium,” the long hallucinated description of riding atop the back of a swift hippopotamus, the juxtaposition of absurdity with respect, an opening into that fantastic. Cubas says no one else has narrated their own delusion before. Then he becomes a Chinese barber:

Shortly thereafter, I felt myself transformed into St Thomas Aquinas's Summa Theologica, a volume bound in Moroccan leather, with silver clasps and illustrations; this idea impressed upon my body the most incomplete immobility; and I still remember that my hands were the clasps of the book, I had crossed them over my stomach, and someone uncrossed them (Virgilia, undoubtedly) because the position made me look like a corpse.

The hippo tells Cubas that they are going to the origin of the ages. The hippopotamus reports that they have passed Eden and as they go, the narrator reflects on what he sees, including the particular silence: "the Silence of that place was like that of the tomb: one might have said that the life and things had fallen stunned in the presence of man." And then the figure of a woman appears, and that figure holds in itself boundlessness, or what the narrator describes as “the vastness of the wilds.” Cubas says nothing at first and then finally asks who she is and what she is named.

She tells him to call her Nature or Pandora:" I am your mother and your enemy."

She tells him not to be frightened because her energy does not kill but rather affirms itself through life: "You are alive: I desire no other torment."

And here, somehow, as the narrator digs his nails into his palm to make sure that he is really alive, the idea of a worm returns as the woman continues:

“Yes, worm, you are alive. You must not fear losing the tattered rags that are your pride; for a few hours yet you shall still taste the bread of pain and the wine of misery. You are alive: now, even in your madness, you are alive; and should your mind retrieve an instant of sense, you will stay that you wish to live."

There's a sense in which the entire reason for wanting to live is undermined by the monologue of the strange woman. But it’s the worm that haunts my notebooks.

Machado dedicates his coffin-composed memoirs to "the worm that first gnawed at the cold flesh of my cadaver" – and he does so fondly ( though the translators introduction says he dedicated it to worms, plural, and this sounds different to me). In a brief chat note, Thomson-DeVeaux said that the worm doesn't come up in the book but her personal opinion is that he dedicated it to that worm as "a sort of reward for having gotten there first."

Later on, in the chapter "Sad, But Short," Cubas witnesses the death of his own tender, kind mother. The next chapter, "Short, But Happy," gives us the response to it, particularly, he has to decide who he is and what he will do in life, the idea of inheritance weighs heavier on him now.

He says that what he learned in university were formulas, skeletons, some Virgil and Horace, things that he could use in conversation but nothing substantial.

" The reader may be taken aback by the frankness with which I exposed and emphasized my own mediocrity; you should recall that frankness is the primary virtue of a late man. In life, the gaze of public opinion, the clash of interests, the struggle between rival greed's obliged as to hide our old rags, to disguise splits and stitches, to not extend to the world that which we reveal to our conscience; and the best of this obligation is when, by dint of diluting others, one dilutes himself, because in this case he is spared humiliation, which is a painful sensation, and hypocrisies, which is a ghastly vice. But in death, what a difference! What an unburdening! What freedom! How we can shake off our cloaks, toss our spangles into the gutter, unbutton ourselves, unpaint ourselves, unadorn ourselves, confess plainly what we were and what we failed to be! because, after all, there are no more neighbors, nor friends, nor enemies, nor acquaintances, nor strangers; there is no audience. The gaze of opinion, that piercing judicial gaze, loses all its power as soon as we set foot in the territory of death; this is not to say that it doesn't reach this far, examining and judging us; but it is we who have no compunctions about the examination or the judgment. My good living sirs and madams, there is nothing so in commensurable as the disdain of the deceased."

In a sense, this “freedom” of death is the freedom from sacrilege. one cannot blaspheme a god from inside the grave.

addenda

In 2020, two new translations of Posthumous Memoirs have appeared almost simultaneously, one translated by Margaret Jull Costa and Robin Patterson (Liveright), who translated Machado's Complete Stories, and the other by by Flora Thomson-DeVeaux (Penguin). In "A Playful Masterpiece That Expanded the Novel’s Possibilities," Parul Seghal compares them and draws attention to the differences. Here’s Borba comparing conscience to why a pretty woman is vain and likes to look in the mirror often: "Conscience...contemplates itself frequently when it finds itself beautiful. Remorse is nothing but the grimace of a conscience that sees itself to be hideous."