To start with the rearview mirror, the hindsight, the way she is framed—the wikipedia entry—

Suzanne Valadon was a French painter who was born Marie-Clémentine Valadon at Bessines-sur-Gartempe, Haute-Vienne, France. In 1894, Valadon became the first woman painter admitted to the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts. She was also the mother of painter Maurice Utrillo.

It is difficult to imagine Valadon outside the time and space of her existence.

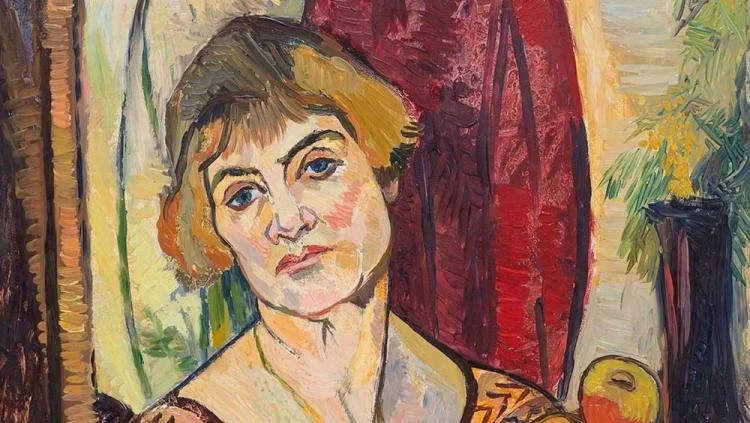

Suzanne Valadon, Nude Arranging Her Hair, ca. 1916; Oil on canvasboard, 41 1/4 x 29 5/8 in.; National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay

At 15, Suzanne Valadon began working as an artist’s model, a demi-mondaine in Montmartre. She modeled for ten years, and posed for artists including Puvis de Chavannes, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Throughout her career, she returned to the naked female body as a subject—one of few women artists painting female nudes during the first half of the 20th century. In her unromantic, frank depictions of flesh, Valadon include nude models and self-portraits.

In Nude Arranging Her Hair, the subject isn’t “sitting for” the artist—she is being depicted in the midst of daily activities. Valadon used unblended lines that refused to soften or airbrush the edges of silhouettes. Given her financial instability, she also used whatever colors she could find or borrow from the male artists who used her as a model. This frugality, she later said, accounts for her attraction to green, which she started using as a leftover. The green flesh-tones, here, are unusual, and exist in a sort of palette dialogue with the background carpet and curtain fabric. According to a museum note, “Valadon often used white, contoured with blue, in her works as a neutral element to set off the values of the surrounding hues.”

Suzanne Valadon, The Circus (1889)

To add the story of origins, the sociological element, the first breath of what could develop a trauma plot—

Born Marie-Clémentine, Valadon was the daughter of an unmarried domestic worker. She grew up in Montmartre, the bohemian quarter of Paris, supporting herself from the age of ten with odd jobs: waitress, nanny, and circus performer.

To include the picture of a neglected child who became the heroine of her own childhood—

Valadon grew up roaming the streets and creating mischief, while her mother worked as a housecleaner. According to Catherine Hewitt, author of Renoir’s Dancer: The Secret Life of Suzanne Valadon, Valadon reported later, “The streets of Montmartre were home to me … It was only in the streets that there was excitement and love and ideas - what other children found around their dining-room tables.” She also called herself a “devil” typically behaving more “like a boy,” and was lucky in many ways, in that she said, “solitude suited me.”

As a child, Valadon was a daredevil who chatted up strangers and admired confrontational, spectacular persons. Authority didn’t impress Valadon. She told people she was the daughter of poet maudit, Francois Villon—and she dressed and acted like Villon, insisting that others call her Mademoiselle Villon.

“I was haunted,” Valadon said later, “As a child, I thought far too much.” Montmarte was heaven for the young Valadon, and when the circus arrived, she saw a space filled with the unconventional, daring sorts of humans that fascinated her. So she worked for the circus. For six months, she rode horses and became an expert on the trapeze. One day, during rehearsal, she fell from the trapeze. The back injury changed her life. Aware of her vulnerability, grieving the fact that she would never be on a trapeze again, Valadon began drawing. She drew and drew and drew. The circus would remain a site in the greens of her palette as well as the ideal she measured conventional life against.

Suzanne Valadon and her son, Maurice Utrillo.

When she modeled, she went by the name Marie—because it sounded exotic, Italian, foreing. Jean-Jacques Henner used Marie’s wist for Melancholy. She played Truth for Vojtech Hynais’ Truth Emerging From the Well. She was a siren in Gustav Wertheimer’s The Kiss of the Siren. The half-lit world of modeling, the double-life, felt easier to inhabit that the pristine one.

*

She gave birth to a bastard son as a teenage, unwed mother, and this son would later become a painter that made more money than Valadon. The story has it that Valadon met Miguel Utrillo at Le Chat Noir at 15—and there was an immediate attraction between them. “At a time when barely anyone paid me any attention, he encouraged me, strengthened me and supported me…. with Michel (Miguel) I spent the best years of my youth…. we lived an artistic and bohemian life,” Valadon said of Utrillo.

Two years later, Utrillo moved away from Paris, but the couple kept in touch and maintained a non-monogamous relationship. When Valadon, at age 18, gave birth to her son, Maurice, she couldn’t get a residence permit for him. Utrillo stepped in and gave the baby his name—he went back and signed the birth certificate as his father, although he probably wasn’t.

Maurice was taken care of principally by Valadon’s mother so that Valadon could continue working as a model and earn money.

Suzanne Valadon. Joy of Life, 1911. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Miss Adelaide Milton de Groot (1876–1967), 1967. © 2021 Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York / Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource, NY.

In 1892 Valadon had an intense six-month love affair with the composer Erik Satie while she was also simultaneously seeing a wealthy banker, Paul Mousis. Eventually the relationship with Satie ended as Valadon refused to commit to him or to end the relationship with Mousis.

Take Stephen Sondheim’s Sunday in the Park with George—subsitute the baker for the banker—and one has the sense of choices females had to make in order to survive. Love has never been the whole story for women. Romantic love is the bourgeois luxury.

To return to the trauma plot she refused, which is to say, the reality of her lived experience—and the story she preferred to tell about her own life. Valadon fell from a trapeze and ruined her back at 15. Her physical daring, or the sense in which she inhabited her body, ended with that fall. Pain would be her quiet partner, reappearing by surprise. But she grew good at reading the faces of others, as one who relies on others must be good at reading them—and she could become anything a man wanted when he asked her to sit, to pose, to play Truth or siren.

*

At the time of Erik Satie's death in 1925, nobody except himself had ever entered his room in Arcueil since he had moved there twenty-seven years earlier. Among the things his friends discovered there, after Satie's burial at the Cimetière d'Arcueil, apart from the dust and the cobwebs (which suggested that Satie never composed using his piano):

enormous quantities of umbrellas, some that had apparently never been used by Satie

the portrait of Satie by Valadon

love-letters and drawings from the Valadon period

other letters from all periods of his life

his collection of drawings of medieval buildings (only now did his friends start to see the link between Satie and certain previously anonymous journal adverts regarding 'castles in lead' and the like)

other drawings and texts of autobiographical value

memorabilia from all periods of his life, amongst which were the seven velvet suits from the Velvet gentleman period, etc.

compositions nobody had ever heard of (or which were thought to have been lost) everywhere: behind the piano, in the pockets of the velvet suits, etc. These included the Vexations, Geneviève de Brabant and other unpublished or unfinished stage works, The Dreamy Fish, many Schola Cantorum exercises, an unseen set of 'canine' piano pieces, several other piano works, often without a title (which would be published later as more Gnossiennes, Pièces Froides, Enfantines, Furniture music, etc.).

*

Most of Satie's letters to Valadon were never sent. Conrad Satie showed these letters to Valadon in 1926, a year after Satie's death, and she chose to burn them.

The one letter Satie mailed to her–on 11 March 1893–reveals that he was deeply in love with Valadon, but even though they both lived at 6 rue Cortot, Satie was upset that he couldn't find 'dates' to meet her, given her commitments to other men, artists, and her son.

*

On April 7, 1938, while painting flowers at her easel, Valadon had a stroke and died. She was buried beside her mother in the cemetery at Saint-Ouen, in the northern suburbs of Paris. André Derain, Pablo Picasso, and Georges Braque were some of the notable male artists who attended her funeral.

Valadon left this world with around 300 drawings, more than 450 oil paintings, and over 30 etchings. Her nudes influenced the art of American painter, Alice Neel, who also depicted aging self-portraits inflected by intense dark lines, over-saturated hues, and casual poses.